July 25, 2023

The Honorable Patrick McHenry

Chairman

House Financial Services Committee

2134 Rayburn House Office Building

Washington, DC 20515

The Honorable Sherrod Brown

Chairman

Senate Banking Committee

503 Hart Senate Office Building

Washington, DC 20510

The Honorable Maxine Waters

Ranking Member

House Financial Services Committee

2221 Rayburn House Office Building

Washington, DC 20515

The Honorable Tim Scott

Ranking Member

Senate Banking Committee

104 Hart Senate Office Building

Washington, DC 20510

RE: Support for the CFPB’s Final Rule Related to Section 1071 of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act

Dear Chair McHenry, Ranking Member Waters, Chair Brown, Ranking Member Scott,

The National Community Reinvestment Coalition (NCRC) and the undersigned organizations are writing to convey our support for the final rule issued by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) regarding Section 1071 of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act. In addition, NCRC and the undersigned organizations oppose H.J. Res. 66 and S.J. Res. 32, which would repeal this critical rule designed to bring much-needed transparency to small business lending.

The implementation of the final rule recently announced by the CFPB will have widespread benefits. By increasing transparency of pricing, terms and conditions, and action taken on applications, 1071 data is likely to curb excessive pricing, reduce abusive terms, and increase access to credit for traditionally underserved small businesses. Lenders will also realize benefits in terms of improved ability to gauge their competitive position in the market and opportunities for them to identify untapped market segments and serve new customers. Furthermore, the estimated compliance costs are minimal when compared to the net income lenders generate from originating small business loans.

The final rule covers banks, credit unions, online lenders, farm credit system lenders, government lenders, and nonprofits, as well as a wide range of lending products, including agricultural credit. It is likely to result in increased lending to underserved businesses, including farms, as lenders will now annually report on their lending broken down by race, ethnicity, gender and sexual orientation of the business owners. Improvements to Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA) data in 1990 and 1993 corresponded with a 70% increase in conventional home purchase lending to Black borrowers, and a 48% increase in lending to Latinx borrowers, from 1993 to 1995.[1] Furthermore, a study by Citigroup estimates that fair access to lending for Black-owned small businesses alone would have resulted in $650 billion in additional business revenue per year, as well as created an additional 6.1 million jobs per year.[2] This shows how increases in lending to underserved small businesses benefit the entire economy by enabling small businesses to expand and create additional job opportunities.

The statutory purpose of Section 1071 is to facilitate enforcement of fair lending laws and enable communities, governmental entities, and creditors to identify business needs and community development opportunities. There is ample evidence of ongoing discrimination in small business lending. NCRC studies have found that White applicants were given significantly better information about business loan products, particularly information regarding loan fees and during the Paycheck Protection Program.[3] Studies conducted by the Federal Reserve have found that Black-owned businesses are less likely to be approved for financing compared with White-owned firms.[4]

The Minority Business Development Agency found that businesses owned by people of color received lower loan amounts than White-owned firms, even after controlling for the sales level of firms.[5] There have been numerous lawsuits regarding discrimination against farmers of color, and the number of black farmers has decreased by 95% from 1910 to 2017.[6] In 1910, Black farmers accounted for 14% of all farmers, in 2017 this was down to just 1.3%. Apparent discrimination in small business lending is not limited to race. One study found that while LGBTQI+ businesses were equally likely to apply for financing, they were less likely to receive it. The same report also noted that LGBTQI+ owned businesses were more likely than non-LGBTQI+ businesses to report their denial was due to lenders not approving financing for “businesses like theirs” (33 percent versus 24 percent).[7]

Besides the critical goal of rooting out discrimination in small business lending, implementation of 1071 will greatly increase understanding of the small business landscape with significant benefits for lenders, government agencies, and researchers. Lenders will now have a great data set that will allow them to assess demand and how small business needs are being served locally, including identifying untapped markets, which will greatly enhance their ability to make sound business decisions as it relates to expansion plans and development of products. This data will also allow lenders to make comparisons to other lenders in their markets, which will aid in measuring compliance risk and correcting potential issues that could come up in fair lending reviews. Besides costs, which this letter will cover how estimated costs are minimal, only lenders with potential fair lending compliance issues should be concerned about improvements to small business lending data, and protecting discriminatory lending practices is an unacceptable policy position favored by no one.

Government agencies will be able to use 1071 data to identify additional opportunities to create new, or tailor existing, programs to advance their small business lending policy objectives. For example, government agencies often create programs that specifically target businesses owned by people of color and women, such as those that reserve government contracts, or provide grants. Government agencies could use 1071 data to improve existing programs or create new ones to meet the needs of these business owners.

For researchers, 1071 data will be similar to HMDA data that is regularly used in academic studies on the mortgage industry. This data will greatly expand the ability of academic research to interpret the landscape of small business lending, which will also benefit lenders and government agencies.

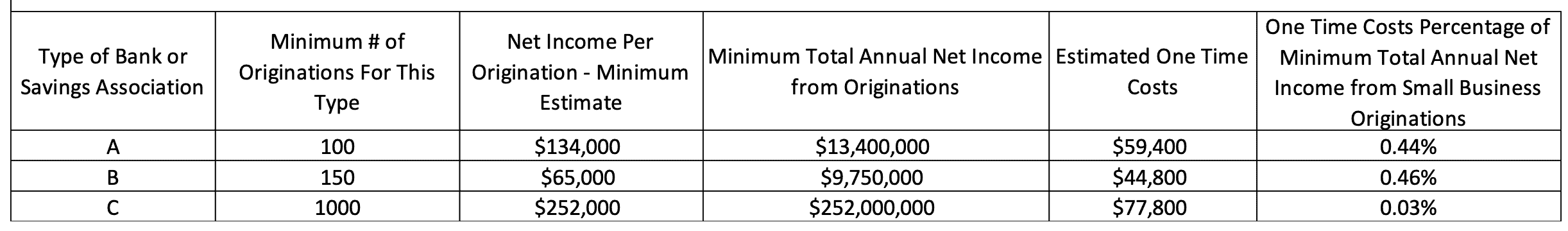

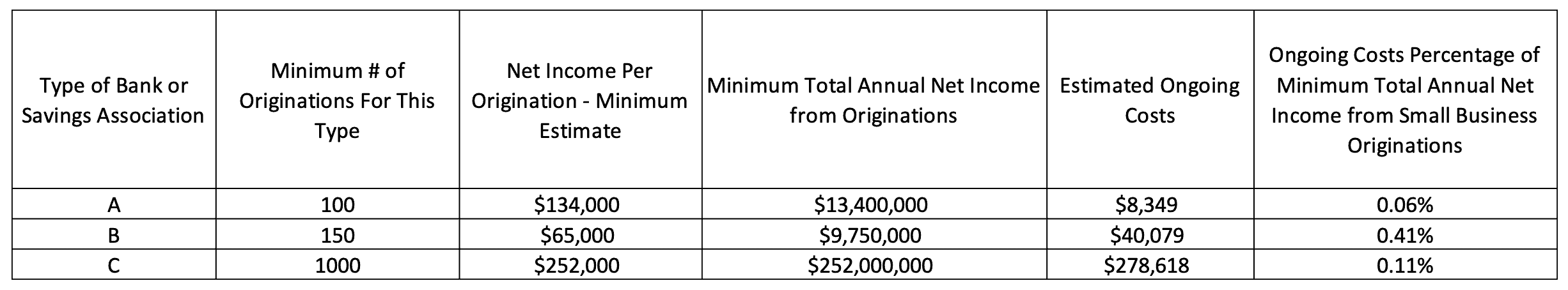

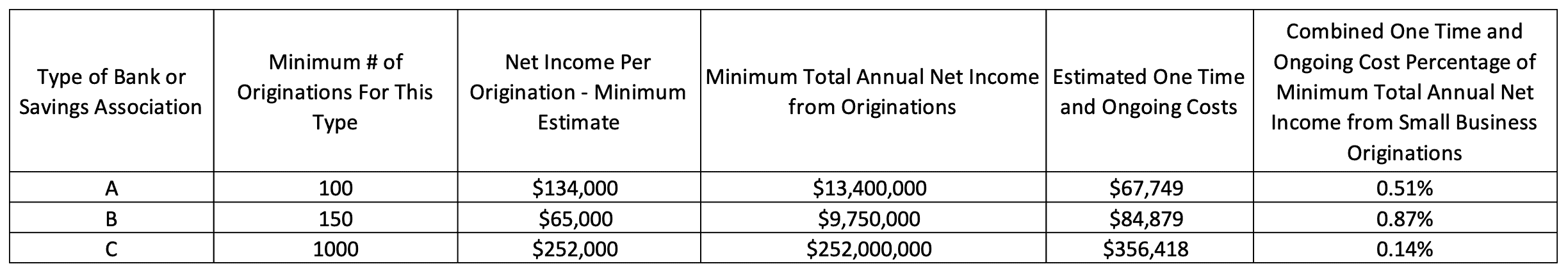

Costs associated with compliance are minimal when factoring in the income lenders generate from originations. The CFPB employed data analysis and surveys of lenders to develop estimates of one-time start-up costs, annual fixed costs, and variable costs determined by the number of applications received. The CFPB grouped depository institutions into three categories based on the number of covered small business loans they originated, and came up with estimates of net income that each category of depository lender generates from originating small business loans.[8] As the charts below show, using costs calculated by the CFPB and minimum estimates of net income from originations, one time and ongoing costs of compliance from deposit taking lenders range from just .1% to .9% of annual net income from originations of small business loans alone.[9]After the one time costs, estimated ongoing costs drop to just .06% to .4% of annual net income these institutions receive from just originating small business loans.

One Time Costs

Ongoing Costs

Combined One Time and Ongoing Costs

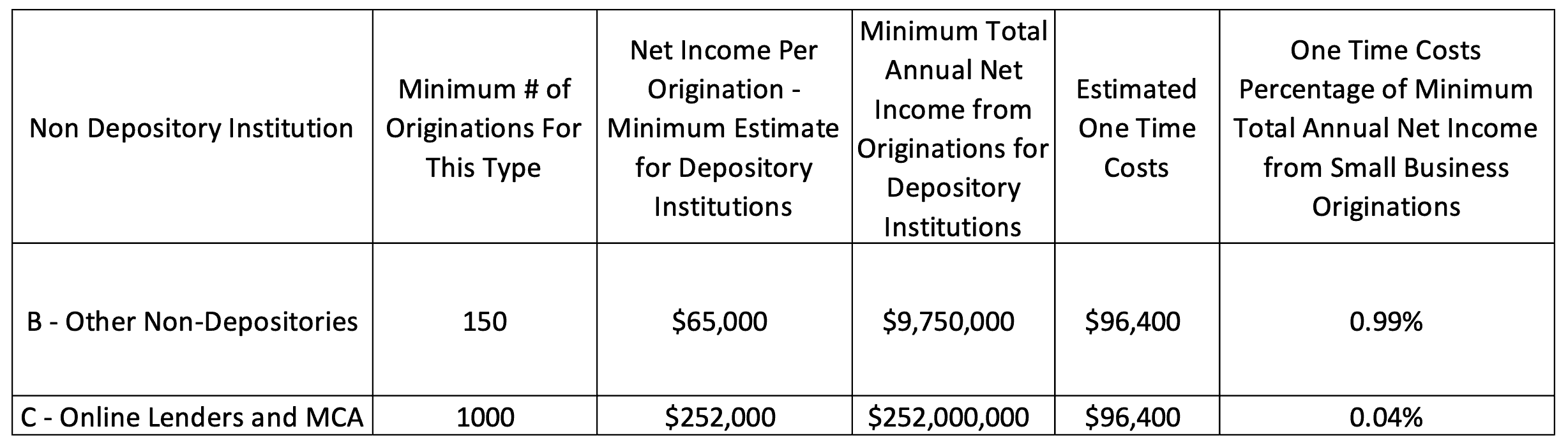

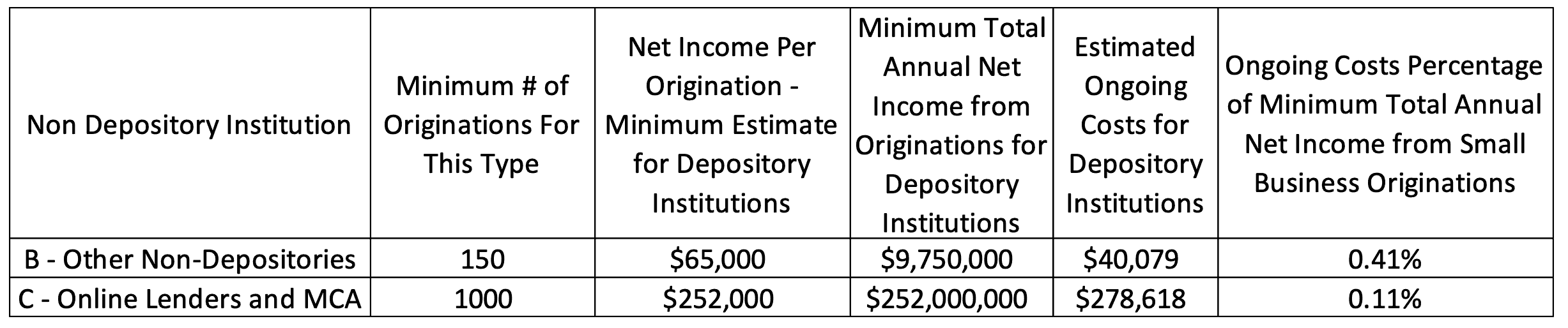

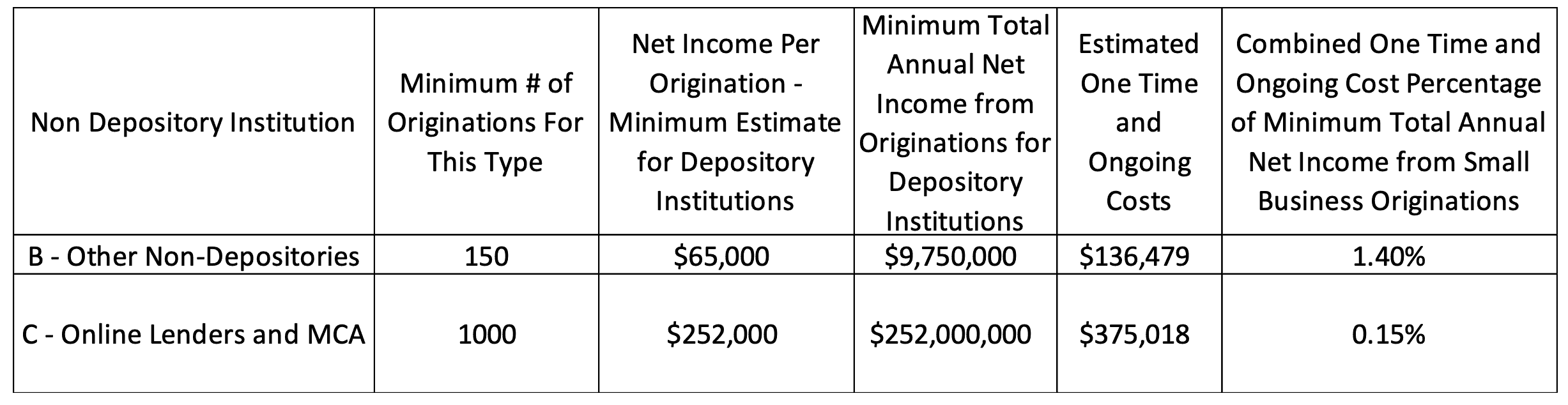

There is less information currently available for non-depository lenders, such as online lenders, so the Bureau was unable to provide specific estimates of ongoing costs and net income from originations for these lenders. However, the Bureau was able to estimate the one time costs for non-depositories, and determined that online lenders and merchant cash advance providers are similar to Type C depository institutions, and the rest of the non-depositories are similar to Type B.[10] When applying the estimated one time costs for non-depositories, and the estimates of ongoing costs and minimum estimates of net income of Type B and C depository institutions, you can see that costs to non-depositories are also expected to be minimal. The charts below show that the combined one time and ongoing costs range from just .2% to 1.4% of estimated annual net income from only originating small business loans. After the one time costs, which are estimated to be higher for non-depositories since many of them have not previously had to do this type of reporting, the ongoing costs drop to just .1% to .4% of estimated annual net income from originating small business loans.

One Time Costs

Ongoing Costs

Combined One Time and Ongoing Costs

Costs to borrowers will also be minor. The CFPB defined a set of costs per application as variable costs and noted that these costs will likely be passed on to applicants. However, the CFPB estimates these costs to be minimal as well, ranging from just $7.50 to $32 in expected additional closing costs.[11]

Finally, the implementation of Section 1071 is unlikely to reduce small business lending or discourage lenders from establishing relationships with businesses that present sound lending opportunities. The tendency of smaller banks to voluntarily report small business and small farm data suggests that data disclosure helps rather than hinders them as they assess marketplace opportunities and comply with the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA). In 2018, 157 or 22% of the 700 institutions reporting CRA small business loan data were smaller banks voluntarily reporting the data.[12] HMDA data was also enhanced in 2004 to require reporting of price information along with additional data points such as lien status. In 2004, 8,121 lenders reported HMDA data and by 2007 the number of reporters increased by 765 to 8,886. Over time, therefore, the number of HMDA reporters grew, which is inconsistent with the argument that data reporting and/or additional reporting requirements causes a decrease of lending or lenders.

Thanks again for considering our views regarding the CFPB’s final 1071 rule and our opposition to H.J Res. 66 and S.J. Res. 32. Implementation of Section 1071 is a great opportunity to reduce ongoing disparities in access to small business credit. Addressing these disparities will make urban and rural economies more vibrant, and bring substantial benefits to all stakeholders, including lenders. If you have any questions, please reach out to Rion Dennis, Senior Director, Government Affairs (rdennis@ncrc.org), Joseph Reed, Senior Policy Advocate (jreed@ncrc.org), or Kevin Hill, Senior Policy Advisor (khill@ncrc.org).

Sincerely,

National Community Reinvestment Coalition

20/20 Vision

Access Plus Capital

Accountable.US

African American Alliance of CDFI CEOs

Alliance 85, Inc.

American Economic Liberties Project

Americans for Financial Reform

Anacostia Economic Development Corporation

ANHD – The Association for Neighborhood & Housing Development

Avenue CDC

BBIF, Inc.

Biirmingham Business Resource Center

Bridgeport Neighborhood Trust

Brotherhood and Sisterhood International

Building Alabama Reinvestment

CAARMA

California Capital Financial Development Corporation

California Community Economic Development Association

CAMEO – California Association for Micro Enterprise Opportunity

Camino Financial, Inc.

CASA of Oregon

Cash Community Development Organization

Catapult Pittsburgh

Catholic charities usa

CDC Small Business Finance

Ceiba

Center for Responsible Lending

Centre for Homeownership & Economic Development Corporation

Centro Cultural

Chicago Community Loan Fund

CHWC Inc.

City of Gary, IN

City of Tampa

CLARIFI

Coalition for Non Profit Housing and Economic Development

Coastal Enterprises, Inc.

Community Enterprise Investments, Inc.

Community Growth Fund

Community Housing Development Corporation

Community Link

Community Reinvestment Alliance of South Florida

Consumer Action

Consumer Federation of America

Delaware Community Reinvestment Action Council, Inc.

Demand Progress

Divine Direction

Economic Action Maryland

Economic Growth Corporation

Empire Justice Center

ExploreUSTV and Travel

Fair Finance Watch

Fair Housing Center of Metropolitan Detroit

Fair Housing Center of Southwest Michigan

Famicos Foundation

Family Resources of New Orleans

FHCNA

First Community Capital

Frayser Community Development Corporation

Gen-Wealth Empowerment

Georgia Advancing Communities Together, Inc.

Greater Cincinnati Microenterprise Initiative

Habitat For Humanity of Michigan

Hawai‘i Alliance for Community-Based Economic Development

HEAL Food Alliance

Henderson and Company

Home Ownership Center of Greater Cincinnati

Homes on the Hill, CDC

Housing and Education Alliance, Inc. (HEA)

Housing Education and Economic Development

Housing Justice Center

Housing Options & Planning Enterprises, Inc.

HousingWorks RI

I Give Back USA

IGNITE! Alabama

Interfaith Center on Corporate Responsibility

Jewish Community Action

JOVIS

Latino Economic Development Center

Latino Leadership Council

Latino Policy Council

Legacy Foundation

Legal Aid Society of San Diego

LINC UP Nonprofit Housing Corporation

Local First Arizona

Local Initiatives Support Corporation (LISC)

Logan Heights Community Development Corporation

Main Street Alliance

Massachusetts Action for Justice

Massachusetts Affordable Housing Alliance

Memorial CDC

Metro Milwaukee Fair Housing Council

Metro North Community Development Corporation

Metropolitan Milwaukee Fair Housing Council

Metropolitan St. Louis Equal Housing and Opportunity Council

MS Communities United for Prosperity (MCUP)

MY Project USA

National Association for Latino Community Asset Builders

National Association of American Veterans, Inc.

National Coalition for Asian Pacific American Community Development (National CAPACD)

National NeighborWorks Association

National Urban League

Native Community Capital

NCRC CDF

Neighborhood Improvement Association

NeighborWorks Southern Colorado

New Future Foundation

New Hope Community Development

New Jersey Citizen Action

New Jersey Institute for Social Justice

New Mexico Community Capital

New York StateWide Senior Action Council

Nichols Temple AME Ministries

North Carolina Housing Coalition, Inc.

Northwest Indiana Reinvestment Alliance

Olive Hill Community Economic Development Corporation, Inc

Opportunity Finance Network

Over-the-Rhine Community Housing

Philadelphia Association of Community Development Corporations

Pima County Community Land Trust

Pittsburgh Community Reinvestment Group

Prosperity Indiana

Public Citizen

Public Good Law Center

REBOUND, Inc.

Reinvestment Partners

Responsible Business Lending Coalition

Revolving Door Project

Rise Economy

River Cities Development Services

River City Housing, Inc.

Roosevelt Southwest Community Development Corporation

San Joaquin Valley Housing Collaborative

SaverLife

Self-Help Enterprises

SLEHCRA

Small Business Majority

South Dallas Fair Park Innercity Community Development Corporation

South Florida Community Development Coalition

Southern Dallas Progress Community Development Corporation

Southwest CDC

Southwest Economic Solutions

Southwest Georgia United

Southwest Neighborhood Housing Services

The Food Trust

The Greenlining Institute

The National Council of Asian Pacific Americans (NCAPA)

The Sacramento Environmental Justice Coalition

Tierra del Sol Housing Corporation

Town of Apex

Ubuntu Institute of Learning

UIC Law School

Universal Housing Solutions CDC

Urban Economic Development Association of Wisconsin (UEDA)

Urban Land Conservancy

Utah Housing Coalition

Vermont Slauson LDC

Washington Area Community Investment Fund

Welfare Reform Liaison Project, Inc.

Wisconsin Black Chamber of Commerce, Inc.

With Action

Woodstock Institute

Working In Neighborhoods

Working Solutions CDFI

cc: Members of the House Financial Services Committee

cc: Members of Senate Banking Committee

cc: White House Legislative Office

[1] “Home Loans to Minorities and Low- and Moderate-Income Borrowers Increase in the 1990s, but then Fall in 2001: A Review of National Data Trends from 1993 to 2001.” NCRC. Available upon request.

[2] “Closing the Racial Inequality Gaps: The Economic Cost of Black Inequality in the U.S.” Citigroup. Available online at https://ir.citi.com/NvIUklHPilz14Hwd3oxqZBLMn1_XPqo5FrxsZD0x6hhil84ZxaxEuJUWmak51UHvYk75VKeHCMI%3D

[3] Disinvestment, Discouragement, and Inequity in Small Business Lending and Lending Discrimination with the Paycheck Protection Program.

[4] Mind the Gap: Minority-Owned Small Businesses’ Financing Experiences in 2018.

[5] Disparities in Capital Access between Minority and Non-Minority-Owned Businesses.

[6] Section 1071 Final Rule Page 167.

[7] LGBTQ-Owned Small Businesses in 2021. Center for LGBTQ Economic Advancement & Research (CLEAR) and the Movement Advancement Project (MAP)

[8] Section 1071 Final Rule. Page 731. Type A depository institutions were defined as those that made fewer than 150 covered originations per year. We used 100 loans as the minimum for this category since that is the final loan threshold established by the CFPB.

[9] Net income per origination estimates can be found in the Section 1071 Final Rule, Page 762.

[10] Section 1071 Final Rule Pages 744 and 752.

[11] Section 1071 Final Rule, Page 766.

[12] NCRC analysis of 2018 CRA small business data found via https://www.ffiec.gov/hmcrpr/cra_fs19.htm.