January 15, 2024

Chief Counsel’s Office

Attention: Comment Processing

Office of the Comptroller of the Currency

400 7th St. SW Suite 3E-218

Washington, DC 20219

Secretary Ann E. Misback

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

20th Street and Constitution Avenue NW

Washington, DC 20551

Assistant Executive Secretary James P. Sheesley

Comments/Legal OES

Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation

550 17th St. NW

Washington, DC 20429

Regulatory capital rule: Amendments applicable to large banking organizations and to banking organizations with significant trading activity. FDIC RIN 3064-AF29, Federal Reserve System Docket No. R-1813, RIN 7100-AG64, Office of the Comptroller of the Currency Docket ID OCC-2023-0008 and RIN 1557-AE78

Director Acting Comptroller Hsu, Vice Chairman Barr, and Chairman Gruenberg:

Thank you for the opportunity to comment on this important advancement in banking supervision.

The National Community Reinvestment Coalition is a network of more than 700 organizations dedicated to creating a nation that not only promises but delivers opportunities for all Americans to build wealth and attain a high quality of life. We work with community leaders, policymakers and institutions to advance solutions and build the will to solve America’s persistent racial and socio-economic wealth, income and opportunity divides, and to make a Just Economy a national priority and a local reality.

The proposed rules are a necessary response to the 2008 financial crisis, during which many institutions were revealed to have hidden their undercapitalization through intentional artifice. The proposed rule will address gaps revealed by the recent set of bank failures.[1] The proposal will complement earlier post-crisis policy adjustments to better calibrate credit risk to the diverse nature of bank balance sheets and add resilience during stressful periods.[2]

The new rule will enhance supervision in several ways. It will introduce sensitivities to source of funds for repayment, create uniform and transparent guidelines for measuring capital requirements, and generally ensure banks have enough capital on hand to weather economic crises.

However, the rules would undermine homeownership and certain community reinvestment activities. If risk weightings for high loan-to-value (LTV) mortgage loans held-for-investment increase dramatically, it may make banks more hesitant to extend mortgage loans to the types of borrowers – typically lower-wealth, lower-income, and of color – who make smaller down payments.

I. The Agencies should adopt the effective but less punitive risk weightings called for in Basel III.

- In an attempt to increase loss-absorption capacity, the Agencies will unnecessarily exceed the capital requirements called for in Basel III.

- The proposed risk weightings are punitive and disproportional to historical loan performance

II. The Agencies Must Reconcile Safety and Soundness Objectives with Priorities for Homeownership

- The overly aggressive capital requirements are likely to make mortgages significantly more expensive for the lower-wealth populations that rely to a greater extent on high LTV mortgages.

- The higher LTV requirements will disproportionally impact access to credit for borrowers of color and to low-and moderate-income (LMI) borrowers

- The proposed rules will increase the utilization of mortgage insurance (MI). However, MI programs are not without their shortcomings.

- The actions of low-wealth borrowers did not threaten bank liquidity. In that context, it is wrong to penalize these households for the impacts of poor capital management by bank leadership. Regulators should hold banks accountable to make data available to the public on their share of uninsured deposits and duration risk.

III. The Agencies should not go forward with proposed rules that may undermine important financial inclusion and community reinvestment activities.

- The agencies should reduce risk weighting for loans originated to a borrower who has completed a housing counseling program or if the loan includes down-payment assistance from a state housing finance agency.

- The Agencies should also reduce risk weightings when the loan has qualified for Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) credit.

- The Agencies should also reduce risk weightings for loans originated through a special purpose credit program (SPCP).

- The agencies should reduce risk-weightings for loans that are qualified mortgages (QM) as defined by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFP).

IV. Aspects of how capital requirements are calculated will introduce sensible safeguards.

- The Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (NPR) will prevent banks from substituting a regulator’s approach with an internal system. Proprietary risk systems failed to properly evaluate risk in the run-up to periods of high levels of bank failures.

- The Agencies are correct to expand the universe of institutions subject to the proposed capital reserve requirements to include those with between $100 billion and $250 billion in assets.

- iii. Because online banking makes it easier to withdraw funds, supervision should adjust how banks can be prepared for sudden surges in withdrawals.

- Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) failed because it had to sell assets at a loss to meet demands for depositor withdrawals. The proposed rule will ensure supervision can consider the implications when assets held on a portfolio fall in value.

I. The Agencies should adopt the effective but less punitive risk weightings called for in Basel III.

1.In an attempt to increase loss-absorption capacity, the Agencies will unnecessarily exceed the capital requirements called for in Basel III.

Currently, federal rules create a capital reserve requirement of 5.25 percent (10.5 percent reserve requirement times 50 percent risk weighting) for all “held-for-investment” mortgages and additional charges for those made by the largest banks. The requirement is not sensitive to LTV ratios.

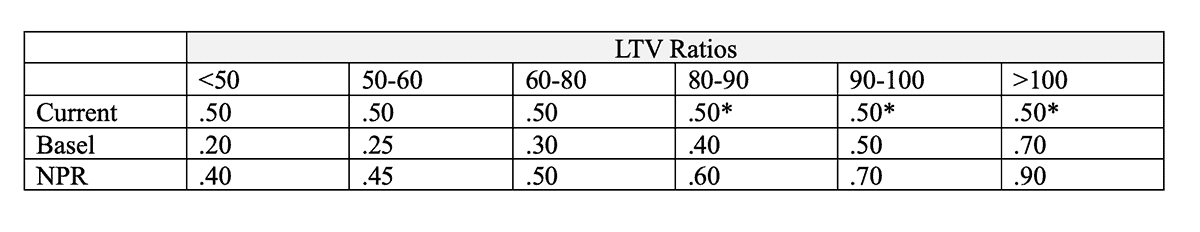

In some loan-to-value (LTV) buckets, the proposed rules would increase risk weightings beyond Basel III standards. In each LTV bucket, risk weightings add 20 percentage points. For example, whereas a 90 percent LTV owner-occupied mortgage loan would currently impose a risk weighting of 50 percent in the United States and for Basel III, the proposed rule would assign a 70 percent risk weight.

[3] *With mortgage insurance

For each LTV bucket, risk weightings in the proposed rule are twenty percentage points higher than the structures called for in Basel.

All else being equal, applying higher risk weights to higher-LTV loans would force covered lenders to set aside more capital. This will necessarily reduce their return-on-assets (ROA). Lower ROAs are anathema to any business. Financial institutions would necessarily equate lending to lower-wealth and high-LTV borrowers with fewer profits. Going forward, should the performance of loans originated to high LTV borrowers remain constant, credit availability would nevertheless decline.

2. The proposed risk weightings are punitive and disproportional to historical loan performance rates.

In response to the proposed capital rule, the Urban Institute recently released an analysis showing that the proposed capital ratios are higher than loss rates experienced by mortgages held by the GSEs during the period of 2005-2008, which were the worst performing mortgages on the GSE books in recent decades.[4] Co-authored by Laurie Goodman and Jun Zhu, the paper calculated delinquency rates, foreclosure rates, and loss rates for mortgages with various LTV and FICO score combinations.

Comparing loss rates with proposed capital ratio requirements for mortgages of various LTV and FICO combinations, the paper found that the proposed capital ratios were excessive because they were higher than the loss rates in one of the lowest performing books of GSE loans. The GSE book of loans from 2005-2008 had an overall loss rate of 6.56%, which was 79 basis points lower than proposed capital requirement of 7.35%.[5] Goodman and Zhu point out that the future loss rate was over-estimated in the paper since many, if not most, of the reckless and abusive loan features from 2005-2008 have a minimal presence in the current mortgage marketplace.

The Agencies should use the Basel III risk weightings for mortgage loans held-for-investment that were originated to owner-occupants. While the additional levels of nuance in the proposed rule may shed more granularity to assessments of mortgage portfolios, the incremental gain on supervisory insight would be attained at great harm. The Agencies should apply Basel III updates, but it is a mistake to go further. The Basel approach and the proposed rule are directionally similar – both penalize banks for high-LTV loans and reduce risk weightings for low-LTV originations. But beyond that, the approaches differ greatly. Most loans originated to owner-occupants will have lower risk weightings in Basel than under the proposed regime. Only loans with LTV’s of more than 100 percent would have risk weightings above 50 percent in Basel while the NPR would apply higher risk weightings for mortgages with LTVs between 80 to 100 percent. Moreover, the risk weightings in the NPR are considerably higher than in Basel as shown in the table above.

II. The Agencies Must Ensure that Safety and Soundness Objectives Can be Met without the Overly High LTV Weights and with Priorities for Homeownership

1.The overly aggressive capital requirements are likely to make mortgages significantly more expensive for the lower-wealth populations that rely to a greater extent on high LTV mortgages.

Current rules create a capital reserve requirement of 5.25 percent (10.5 percent reserve requirement times 50 percent risk weighting) for all mortgages and additional charges for those made by the largest banks. The requirement is not sensitive to LTV ratios.

The new rule (as discussed in greater detail below) introduces a new approach to assessing the credit risk of mortgages held-for-investment. The proposal draws distinctions between the source of funds – from the owner or through rents – and by LTV buckets.

Goodman and Zhu calculated that for a $200,000 mortgage with an LTV between 90% and 100%, the borrower would face an extra $33 monthly cost.[6] Over several years, this makes the mortgage considerably more expensive and would either reduce equity accumulation for many borrowers or would disqualify several loan applicants when underwriting determined that they could not afford the extra cost.

A review of the literature suggests that delinquencies and defaults increase as LTVs increase, however, compensating factors such as good creditworthiness can significantly mitigate the increase in delinquencies and defaults. This suggests that LTV ratios are not a sufficient measure for establishing risk weights.

A working paper authored by economists with the Federal Housing Finance Administration (FHFA) used data from mortgages sold to the Government Sponsored Enterprises (GSEs) during 1995 through 2008. The paper found that as LTV increased, so did the delinquency and foreclosure rate. However, the increase in non-performing mortgages was considerably less for high LTV mortgages in cases in which the borrowers had good creditworthiness as reflected by high FICO scores. The paper stated, “For instance, if LTV was raised from 80 percent to 90 percent for borrowers with a FICO score of 620 in the GSE market segment, the foreclosure rate would increase by 4.46 percentage points. In comparison, the same change in LTV would result in an increase of foreclosure rate by only 2.23 percentage points for borrower with a FICO score of 700.”[7] This increase in the FICO score substantially reduced the foreclosure rate increase by about half. Likewise, a report conducted for the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) found that the probability of default would remain unchanged if the LTV increased by 20 percentage points, but the credit score increased by 100 points.[8]

Important research conducted by Ding, Quercia, Li, and Ratcliffe underscored that prudently underwritten mortgages with high LTV ratios but made to borrowers with good credit scores can perform well. During the height of subprime lending in the early to mid-2000’s, the authors compared the performance of high interest-rate subprime loans to a nonprofit lending product called the Community Advantage Program (CAP). The CAP loans were issued at prime rates and had features associated with prime loans such as 30-year fixed rates and no prepayment penalties.[9] Most of the CAP loans had LTVs above 97 percent but 63 percent of the borrowers had FICO scores above 660 and 31 percent has FICO scores above 720.[10] When making all observed characteristics equal between the subprime and CAP borrowers, the researchers found that the subprime borrowers were three to five times more likely to default on their loans.[11]

Overall, the research suggests that the agencies must rethink their proposal to rely on LTV as a risk weighting factor.

2. The overly aggressive capital requirements are likely to make mortgages significantly more expensive and unattainable for the lower-wealth populations that rely to a greater extent on high LTV mortgages.

The rules will add another hurdle to first-time homeownership. Requirements to make a substantial down payment will prevent many otherwise credit worthy loan applicants from attaining homeownership.

Only a subset of American households put down more than twenty percent when they buy a home. In recent years, the median down payment contributed by buyers under the age of 32 was 8 percent. Indeed, the higher risk weightings would influence the treatment of mortgages originated to almost all working-age households. For those under 42, the number was only slightly higher at 10 percent, and down payments made by applicants younger than 57 was still only 15 percent. These numbers reflect home purchases made in 2022.[12]

The proposed rules could have the effect of encouraging banks to tighter loan underwriting guidelines for young people. Today, most younger homebuyers spend more than three years waiting to buy a home. The recent relentless increases in the cost of housing would probably add to the impact of the rule and could push the dream of homeownership further away from millions of prospective buyers and make them wait even more years.

3. The higher LTV requirements would disproportionally impact access to credit for borrowers of color.

Due to differences in wealth compared to white and Asian households, Black and LatinX borrowers are more likely to make smaller down payments. In 2020, median wealth of Black households lagged white households by a factor of six.[13] Because these figures capture home equity, gaps may increase in magnitude over future years due to differences in value appreciation in predominantly Black and white neighborhoods.

Sources of wealth inequalities among first-time homebuyers, who do not have home equity, will come from stock and savings. When controlling for income level, these disparities remain. Middle-class Black households have half of the stock holdings of their white counterparts.[14] Without equity, the median wealth of Black first-time homebuyers is more likely to fall well below a down payment of twenty percent or more. Moreover, research suggested the impending transfer of wealth from baby boomers to younger generations will exacerbate racial inequality on an absolute basis.[15]

Initial research by industry hinted that increasing risk-weighting for higher LTV loans will have the greatest impact on mortgages originated to Black borrowers. In 2022, more than half of loans originated to Black borrowers had down payments of less than 20 percent, which suggests that more than half would have risk weightings increasing by 20 basis points, compared to only one in five for white borrowers.[16]

The Urban Institute’s research corroborated these findings. The Institute revealed that the new homebuying clients of the NeighborWorks counseling program were more likely to be low-income, women, African American, and Hispanic, who are more likely to use low downpayment and higher LTV loans, than the general population of borrowers of home purchase loans.[17] The recent Goodman and Zhu paper further confirmed this, finding that 9% of bank loans with 80% or higher LTVs were issued to African Americans compared to 5% of all bank loans. These disparities were likewise significant for Hispanics and LMI borrowers.[18]

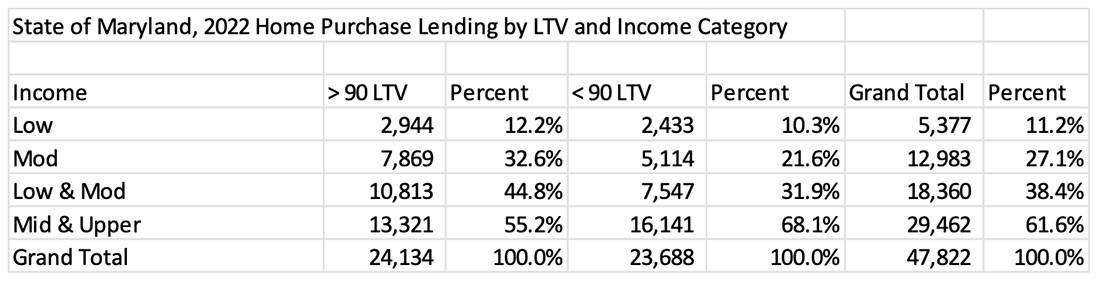

4. Greater Risk Weights for High LTV Mortgages Would Target LMI Mortgages

The proposed higher risk weighting for higher LTV mortgages would capture a disproportionate percentage of mortgages made to low- and moderate-income (LMI) borrowers. NCRC analyzed HMDA data for 2022 in the state of Maryland. Although this is not a national sample, Maryland has a diversity of geographical areas ranging from large metropolitan areas, smaller cities to rural areas. Thus, it is likely that the results of this analysis would be like those for several other states. We encourage the agencies to conduct further research along these lines.

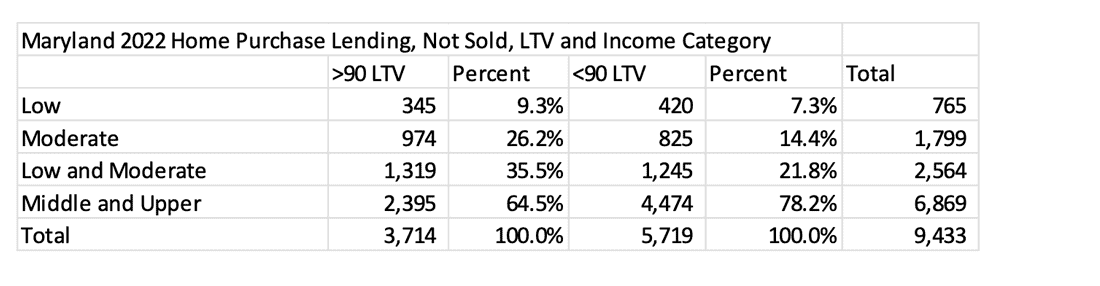

We chose a subset of HMDA data: originated, first-lien, single family, conventional home purchase loans made to owner-occupants.[19] The first table below shows that 44.8% of the loans with LTVs above 90% were issued to LMI borrowers. In contrast, 31.9% of the loans with LTVs below 90% were issued to LMI borrowers. A similar result occurred when restricting the sample to loans not sold (or held in lenders’ portfolios – most likely banks). In the second table displaying loans not sold, 35.5% of the loans with LTVs greater than 90% were issued to LMI borrowers while just 21.8% of the loans with LTVs below 90% were issued to this group of borrowers.

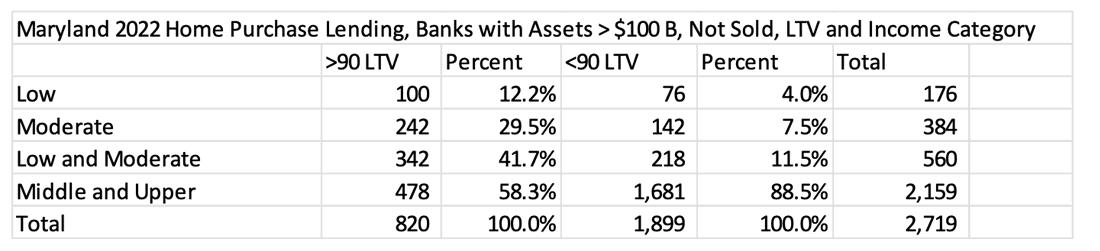

The results become even more exaggerated in terms of a disproportionate amount of portfolio loans (not sold) with high LTVs to LMI borrowers when considering loans made by banks with assets above $100 billion (these are the banks that would be subject to the new risk weighting). Table 3 below shows that 41.7% of the high LTV loans were issued to LMI borrowers while only 11.5% of the loans with low LTV loans were received by LMI borrowers.

Table 1

Table 2

Table 3

Another perverse aspect of the proposed higher risk weights is that using high LTVs focuses on a small share of total mortgage lending that is likely to be related to CRA and Special Purpose Credit Program (SPCP) affordable lending. In the second table, only 345 high LTV loans not sold were made to low-income borrowers and only 974 were issued to moderate-income borrowers. This LMI total of 1,319 home purchase loans is just 2.7% of the total (sold and not sold) conventional home purchase loans issued in the state of Maryland during 2022. All high LTV loans totaled 3,714 and were 7.7% of all loans (sold and not sold). The portion is even smaller when considering banks subject to risk weighting. Table 3 shows that LMI borrowers received 342 high LTV loans and that high LTV loans to all income groups were 820. This amounted to .71% and 1.7%, respectively, of all conventional home purchase loans (sold and not sold).

Thus, the proposed risk weights would make a small part of mortgage lending, particularly lower downpayment lending to LMI borrowers, more expensive while not effectively ensuring that the majority of mortgage lending is appropriately considered in terms of its riskiness. It is unlikely that the small portion of LMI lending poses undue risk to banks whereas any increase in general riskiness of underwriting practices is likely to affect a broader swath of lending that poses a threat to the financial system as experienced during the financial crisis.

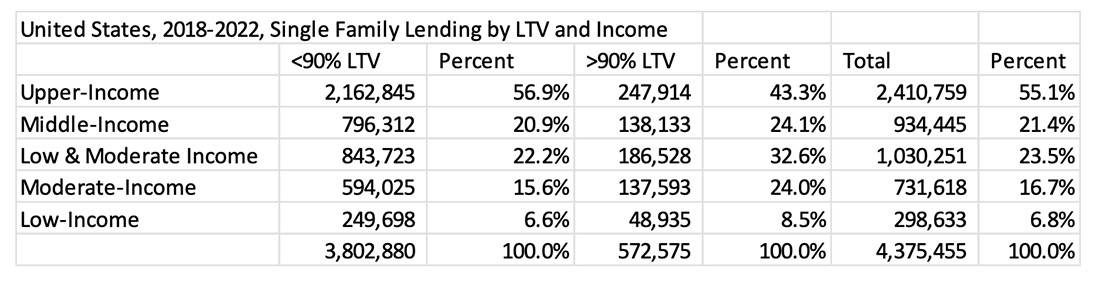

Extending our analysis, NCRC also considered first lien, single-family lending (home purchase and refinance) to owner-occupants on a national level from 2018 through 2022. The analysis included only banks with at least $100 billion in assets and subject to the proposed risk weights. The results were similar to those in Maryland. The share for LMI borrowers was once again higher for loans with LTV above 90%. Banks issued 22.2% of their loans with LTVs below 90% to LMI borrowers but 32.6% of their loans with LTVs above 90% to LMI borrowers as displayed in Table 4.

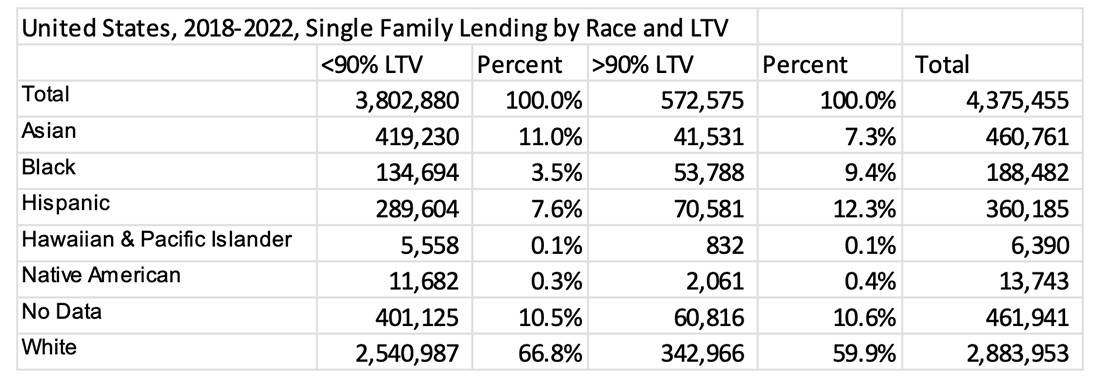

Table 5 shows that people of color would also receive a disproportionate portion of high LTV loans and be subject to the higher risk weights. In particular, banks issued 9.4% of their high LTV loans to African Americans but only 3.5% of their loans with LTVs below 90% to African Americans. For Hispanics, the disparity was almost 5 percentage points in favor of high LTV loans. In contrast, Asians and whites had a higher percentage of low LTV loans than high LTV loans. Thus, the proposed risk weights would translate into higher loan costs for African Americans and Hispanics, parts of the population with the least amount of wealth and least able to afford the higher costs that are not justified based on risk as revealed by the Urban Institute above.

When comparing the national and Maryland analysis, a major finding is that the disparity in terms of higher LTV loans for LMI populations is worse in home purchase lending only as shown above in the Maryland tables than when considering home purchase and refinance lending on a national level. The proposal would therefore likely impose the highest costs on many LMI borrowers who are first time homebuyers and are seeking entrance into homeownership and the lending markets. This is the population that public policy would want to avoid burdening. And in this case, it is feasible and possible to avoid burdening them and impeding their equity building.

Table 4

Table 5

5. The proposed rules will increase the utilization of mortgage insurance (MI). However, MI programs are not without their shortcomings.

The agencies have proposed that mortgages issued with Federal Housing Administration (FHA) or Veterans Administration (VA) guarantees would be weighted at 20%.

By itself, the lower risk weighting should ensure banks are not reticent to originate mortgages with government guarantees. However, this will only amplify some of the tradeoffs associated with government guaranteed loan programs.

FHA mortgage guarantees increase access to homeownership by permitting borrowers to buy homes with a lower down payment. However, borrowers pay more in fees when they have to purchase mortgage insurance as a condition of receiving a loan.

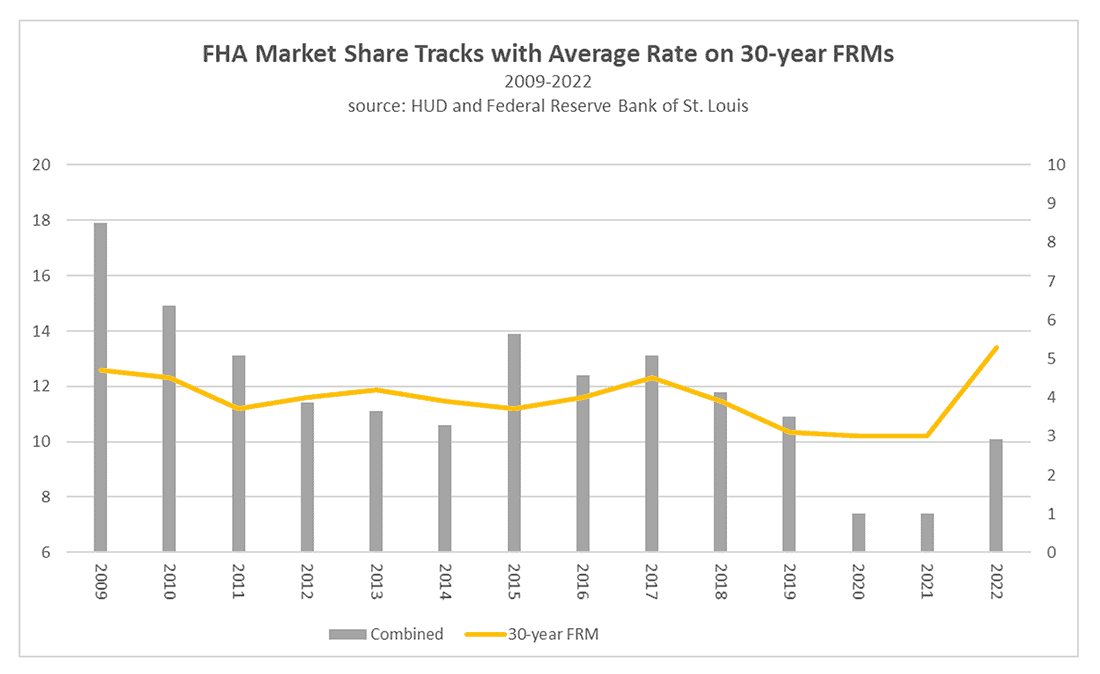

Additionally, only some financial institutions (FIs) participate in FHA or VA loan programs. The share of FHA originations peaked immediately after the financial crisis. However, use of FHA has fallen since 2015. Today, FHA accounts for 10 percent of all originations. During the low interest rate environment in 2020 and 2021, use of FHA plummeted to historic lows as shown in the table immediately below.

Between 2009 and 2022, FHA market share and 30-year FRM rates exhibited a correlation of 60.9 percent.

While there are many virtues of the support FHA contributes to homeownership, it is nonetheless the case that the all-in price of FHA loans is greater than conventional ones. The correlation between higher share of FHA lending and increases in mortgage interest rates suggests a near-future where more low-wealth borrowers turn away from conventional and shift to FHA particularly in higher interest rate environments. It is not clear why federal policy should further exacerbate this shift with lower risk weights for FHA lending when such lending is more expensive for low-wealth borrowers.

6. The actions of low-wealth borrowers did not threaten bank liquidity. In that context, it is wrong to penalize these households for the impacts of poor capital management by bank leadership. Regulators should hold banks accountable to make data available to the public on their share of uninsured deposits and duration risk.

Silicon Valley Bank failed because it did not manage interest rate risk and was not prepared to weather a sudden withdrawal of its deposits.

The bank had made a “duration bet” that soured when their positions in long-term bonds fell in value in response to increases in the Federal funds rate (FFR). The lack of foresight over interest rates made the bank vulnerable. Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) had to sell $21 billion in bonds, at a loss of $1.8 billion, to meet demands from depositors for funds.[20] Account holders withdrew $40 billion in one afternoon and were prepared to withdraw even more on the following business day, but regulators stepped in to take over the bank.

The problem was exacerbated by the fact that an unusually high share of SVB’s deposits were uninsured. Eighty-eight percent of SVB’s deposits were uninsured. At Signature Bank, approximately 90 percent were uninsured.[21] These were disasters waiting to happen. While the data existed to document the problems, the data was buried deep in obscure government data websites and not where the public could readily find it.[22]

Consumers express trust when they deposit their dollars into a bank. For the most part, consumers perceive all banks to be equally sound. That is largely because of the faith held by the public in the FDIC’s deposit insurance program. Thus, it was a surprise for many to learn that such a high share of deposits was uninsured, and to learn the extent of insurance coverage varied greatly among banks. Nonetheless, this was not a surprise to analysts and regulators, because they knew to access call report data.

Two simple fixes could empower the public to identify when a bank is taking unnecessary risks.

First, regulators should inform the public when banks have high rates of uninsured deposits. Consumers deserve to have this information. Regulators can do this without additional data collection – as the Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council (FFIEC) already collects and publishes the information on a quarterly basis.

Releasing and publicizing this information would benefit competition in the marketplace. If a bank felt its reliance on high-dollar deposits might lead to doubts about its safety and soundness, it could respond by increasing efforts to attract deposits from lower-wealth consumers. The benefits to the public would be manifested in higher interest paid on deposits and better terms for checking as banks competed more vigorously for deposits from the public.

Second, regulators should require banks that want to access the Fed window to reveal the amount of interest rate risk held on their balance sheets. By revealing the average duration and yield of their held-for-investment portfolios to the public, bank managers would face accountability from investors, policymakers, and other stakeholders. Actions called for in the proposed rule will give regulators this information, but there would be incremental benefit if a simplified but uniform set of numbers were released publicly.

III. The Agencies should not go forward with proposed rules that may undermine important financial inclusion and community reinvestment activities.

The proposed rule may undermine efforts to support homeownership, small business development, and community development activities. Unless altered, the new requirements will not distinguish between socially-beneficial lending and traditional lending.

The agencies are cognizant that lending programs and products associated with the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) often involve low down payments as well as grants and subsidies to cover closing costs and reduce down payments. Thus, CRA loans are often high LTV loans. The agencies do not want to reduce safe and sound CRA-related lending. They ask for views regarding alternatives to risk weighting based on LTV.[23]

1.The agencies should reduce risk weighting for loans originated to a borrower who has completed a housing counseling program or if the loan includes down-payment assistance from a state housing finance agency.

Research by the Urban Institute has illustrated the benefits of housing counseling. Their findings are the product of a wide variety of sources, including data from the NeighborWorks programs, Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA), and proprietary information. Using data from 2010 through 2012, Urban Institute researchers found that borrowers using the NeighborWorks programs had delinquency rates 16% lower than comparable borrowers that did not use NeighborWorks programs.[24] An earlier Urban Institute study revealed that the rate was about one-third lower during the years of 2007-2009.[25] These were years of high levels of irresponsible and high-cost subprime loans. During a time period of deregulation and abusive lending, counseling played an important role in protecting safety and soundness.

Providing an implicit support for loans made through housing counseling programs will directly support efforts to foster racial equity and to close gaps in black-white homeownership.

Relatedly, many states housing finance agencies (HFAs) offer down payment assistance to borrowers who meet means tests. Typically, these programs include some kind of homeownership education program. While many work through relationships with HUD-certified housing counselors, such partnerships are not mandatory. Nonetheless, relief from increased risk weightings would be consistent with counseling programs operated by HFAs.

Mortgage loans originated to borrowers who have received pre-purchase housing counseling perform well.[26] The Agencies should distinguish those loans from other loans. Conventional loans made through housing counseling should have a risk weight of 50 percent or less.

2. The Agencies should also reduce risk weightings when the loan has qualified for CRA credit, and for loans that are qualified residential mortgages.

Many CRA-qualifying mortgage loans permit low or no down payment. Often, such exceptions to traditional underwriting are necessary to qualify otherwise creditworthy LMI income applicants.

CRA-related lending has served as a shield against higher delinquency and defaults, particularly during years of market volatility and abusive lending. Reid and Laderman compared the performance of CRA-covered banks to non-CRA covered mortgage companies, using the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA) data and proprietary data to control for a wide range of lender, borrower and loan characteristics. They found that loans issued by banks in their assessment areas were about half as likely to result in foreclosure as loans issued by non-CRA covered mortgage companies during 2004-2006, which was the height of subprime and irresponsible lending.[27]

A significant amount of CRA-related lending made to LMI borrowers are likely to involve LTVs of 90% or more. It is counterproductive to weigh these loans more heavily and make them costlier for banks to originate when the research demonstrates that over time CRA related lending has had a good safety and soundness track record.

In addition, NCRC urges the federal bank agencies to better coordinate their proposed capital rule with the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau’s Qualified Residential Mortgage (QRM) rule. In the NPR, the agencies suggested that mortgage-backed securities consisting of qualified residential mortgages (QRM) with prime rates would carry low credit risk, as opposed to non-QRM mortgages with higher subprime interest rates that would be considered higher risk.[28] This commentary implies that QRM mortgages would have lower risk weights than the non-QRM mortgages.

In the years leading up to the financial crisis, the product features causing delinquencies and defaults were unfair, deceptive, and dramatically increased the cost of loans for unsuspecting borrowers. These included adjustable mortgage rates with rapidly increasing interest rates, prepayment penalties, balloon payments, high fees, and no or limited documentation of borrowers’ incomes.[29] The CFPB’s QRM Rule generally limits or prohibits many of these features for loans considered QRM loans and which receive various legal protections.

As discussed above, the agencies reviewed alternatives to using LTV ratios to assign weights. One alternative was assigning a 50% weight to mortgages that were prudently underwritten. It would seem logical that the CFPB’s QRM definition would identify prudently underwritten mortgages. Moreover, the vast majority of CRA and SPCP mortgages would comply with the QM definition.

3. The Agencies should also reduce risk weightings for loans originated through a special purpose credit program (SPCP).

The ability of various factors such as good credit to compensate for higher LTVs further casts doubt on reliance on LTV for risk weighting in the case of affordable lending programs associated with SPCPs. To overlay SCPC programs with higher risk weights – which typically feature low down payments – would fundamentally undermine the availability of these products in the market. SPCPs, by their regulatory definition, are designed for loan applicants that would otherwise not qualify for a loan through a bank’s standard underwriting policies.[30]

The proposal should not change risk weightings for mortgage loans held-for-investment that were originated in the context of a HUD-certified housing counseling program, for QRM loans, for loans that received CRA credit, or for loans that were a part of an approved Special Purpose Credit Program.

IV. Aspects of how capital requirements are calculated will introduce sensible safeguards.

By applying Basel III standards to supervision of the US banking system, the Agencies are proposing to make a significant step to enhance safety and stability of our economy. By applying new levels of sensitivities to evaluations of risk, the Agencies’ proposal will give regulators better information. By making those standards uniform, it will prevent financial institutions from using opaque internal models.

We support the proposed rule, with one exception. Our comments above highlight places where we believe the Agencies will harm traditionally-underserved communities. Regardless, the problems leading to the recent bank failures must be addressed and the Agencies are directionally right for choosing to do so.

1.The NPR will prevent banks from substituting a regulator’s approach with an internal system.

We support the principle of preventing banks from choosing how their risk allocations will be reviewed. Because risk-based pricing permits lenders to increase interest rates for higher-risk loans, banks have an incentive to maximize risk on their balance sheets up to the level permitted by regulation. Because riskier assets carry a higher rate of expected return, banks can increase profits if they take more risk.[31] So, risk weighting is an essential tool to counter profit motives.

Proprietary risk models were one of the contributors to the financial crisis.[32] Because it is difficult to evaluate novel approaches to measuring risk, and because there is a payoff for banks to shroud their risk from supervisors, establishing standard approaches has the benefit of being simpler, uniform, and transparent as well as better protecting the safety and soundness of the banking system. As well, it improves the nature of competition in the market by removing a “race to the bottom” threat. Certainly, a bank may develop internal models that support their assessments of their risk-taking, but there must be standard models to permit regulators to determine how loss-absorption capacity is evaluated.

The rule will ensure transparent and consistent approaches to risk mitigation across the banking industry. In doing so, the new rules will support competition in markets. It will prevent a “race-to-the-bottom” scenario where policies at banks encourage risk-taking. The recent bank failures attest to the truth of the idiom that some companies want to privatize profits but socialize losses.

By requiring a universal and consistent approach to risk-weighting, the agencies will prevent risk-hungry lenders from seeking to gain advantage in the market through evasions of compliance. Such a change will protect depositors and the overall economy.

2. The Agencies are correct to expand the universe of institutions to include those with between $100 billion and $250 billion in assets.

The proposal would revoke changes brought about by an Economic Growth, Regulatory Relief, and Consumer Protection Act (EGRRCPA) rulemaking. This rulemaking had reduced standards of supervision for Category IV institutions (between $100 billion and $250 billion in assets).

Silicon Valley Bank grew from $71 billion to $211 billion from 2019 to 2021, an expansion that occurred immediately after a rule change loosened supervisory standards on Category IV banks. Even though SVB had a higher-than-average share of uninsured deposits, a concentrated exposure to a volatile economic sector, and deficiencies in its interest rate risk management, it received satisfactory ratings on its safety and soundness reviews.[33] The right conclusion to draw from the events that followed, where a handful of other banks also experienced deposit outflows, is that even a bank with fewer than $250 billion in assets can pose a risk of contagion.

The SVB bank failure underscores why the agencies have taken the right step in proposing to apply heightened capital requirements (the expanded risk-based approach) to all financial institutions with more than $100 billion in assets and also to require them to calculate their regulatory capital using the same methods as Category I and II institutions.

3. Because online banking makes it easier to withdraw funds, supervision should adjust how banks can be prepared for sudden surges in withdrawals.

The SVB failure demonstrated how online banking has expedited the speed of banking runs. Within hours after news stories revealed SVB’s liquidity problems, SVB account holders withdrew $42 billion. Overnight, customers made withdrawal orders of another $100 billion. The Federal Reserve shuttered SVB at that point. These sums represented 81 percent of deposits.[34] In light of how quickly SVB deteriorated, regulators must conclude that digital banking has created a new challenge to prevent bank runs. Action must occur within hours rather than days or weeks. The issue underscores the importance not just of capital adequacy but also of liquidity.

We support the decision to increase capital reserves. The speed of deposit flight adds difficulty to preventing a bank failure. The fundamental response in this proposed rule is to force banks to build better defenses ahead of time. By requiring banks to hold more funds in reserve, and making risk-weightings more sensitive to complex business models, the proposal accomplishes this goal.

4. SVB failed because it had to sell assets at a loss to meet demands for depositor withdrawals. The proposed rule will ensure banking supervisors can consider the implications when assets held on a portfolio fall in value.

The proposal would require banks to adjust their balance sheets to reflect changes in the value of their holdings. The failure of SVB occurred because long-term mortgage-backed securities held by SVB lost value when interest rates increased. This outcome was entirely foreseeable, as the Federal Reserve had signaled its intent to increase its funds rates more than a year before SVB failed. The impact on its value presented risk. However, rules revised in 2019 constrained the ability of regulators to act.[35]

The proposed rule makes the logical response to fix the problem. It requires assessments of tier 1 capital to reflect all unrealized gains and losses on available-for-sale securities (save for those associated with hedged items) for banks in Categories III and IV. This will make treatment of smaller institutions consistent with larger ones. If this had been in place before, the gradual deterioration in SVB’s balance sheet would have been reflected in its regulatory capital ratios and would have provided a real-time understanding of bank liquidity.

We support the proposal’s intention to increase loss-absorbing capacity restrictions on less-liquid trading positions.

Conclusion

The recent bank failures illustrate the significance of deposit insurance to the stability of banks. When SVB was forced to sell bonds at a loss, it alarmed its depositors. But the degree of concern among those depositors pivoted on a single factor – the surety of their funds. Because almost 80 percent of SVB’s deposits were uninsured, the bank was vulnerable to any loss of trust among its customers.

The event illustrates the benefit conveyed to banks by deposit insurance. It should serve as a reminder that deposit insurance is a privilege, and it should underscore why this privilege makes it incumbent on insured depositories to meet their community reinvestment obligations. The aspects of the NPR that would make it more costly for banks to meet their reinvestment obligations and would either reduce access to credit for traditionally underserved borrowers or make the credit more expensive must be reworked.

Thank you for the opportunity to comment on this important matter. If you have any questions, please contact me at jvantol@ncrc.org or Josh Silver, Senior Fellow, at jsilver97@gmail.com.

Sincerely,

Jesse Van Tol

President and CEO

[1] Martin Gruenberg. (2023, June 22). Remarks by Chairman Martin J. Gruenberg on the Basel III Endgame at the Peterson Institute for International Economics. https://www.fdic.gov/news/speeches/2023/spjun2223.html

[2] Rosengren, E. (2013, February 25). Bank Capital: Lessons from the U.S. Financial Crisis. Bank for International Settlements Forum on Key Regulatory and Supervisory Issues in a Basel III World. https://www.bostonfed.org/news-and-events/speeches/bank-capital-lessons-from-the-us-financial-crisis.aspx

[3] Mortgage Bankers Association. (2023). Basel III Bank Capital Proposal – MBA Summary [White Paper]. https://www.mba.org/docs/default-source/policy/white-papers/mba_summary_of_bank_capital_proposal_august_2023-resi_cref_8-30-23.pdf?sfvrsn=efa961b8_1

[4] Laurie Goodman and Jun Zhu, Bank Capital Notice of Proposed Rulemaking: A Look at the Provisions Affecting Mortgage Loans in Bank Portfolios, Urban Institute, September 2023, https://www.urban.org/research/publication/bank-capital-notice-proposed-rulemaking, p. 4

[5] Goodman and Zhu, p. 6.

[6] Goodman, L., & Zhu, J. (2023). Bank Capital Notice of Proposed Rulemaking [Housing Finance Policy Center]. Urban Institute. https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/2023-09/Bank%20Capital%20Notice%20of%20Proposed%20Rulemaking.pdf

[7] Ken Lam, Robert M. Dunsky, Austin Kelly, Impacts of Down Payment Underwriting Standards on Loan Performance – Evidence from the GSEs and FHA portfolios, Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA) Working Paper 13-3, December 2013, https://www.fhfa.gov/policyprogramsresearch/research/paperdocuments/2013-12_workingpaper_13-3-508.pdf, p. 18.

[8] Research Report for Importance of Mortgage Downpayment as a Deterrent to Delinquency and Default as Observed in Black Knight (McDash) Servicing History, U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, April 2017, https://www.huduser.gov/portal/sites/default/files/pdf/Downpayment-FinalReport.pdf, p. 21.

[9] Lei Ding, Roberto G. Quercia, Wei Li, and Janneke Ratcliffe, Risky Borrowers or Risky Mortgages Disaggregating Effects Using Propensity Score Models, Journal of Real Estate Research (JRER) Vol. 33 No. 2 – 2011 p. 251, https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/6785666.pdf

[10] Ding, et. al, p. 253

[11] Ding et. al., p. 271

[12] National Association of Realtors Research Group, 2022 Home Buyers and Sellers Generational Trends Report, p. 85, https://www.nar.realtor/sites/default/files/documents/2022-home-buyers-and-sellers-generational-trends-03-23-2022.pdf

[13] Ellora Derenoncourt, Chi Hyun Kim, Schularick, M., & Moritz Kuhn. (2022). Wealth of Two Nations: The U.S. Racial Wealth Gap, 1860-2020 | Opportunity & Inclusive Growth Institute (Working Paper 59). Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. https://www.minneapolisfed.org/research/institute-working-papers/wealth-of-two-nations-the-us-racial-wealth-gap-18602020

[14] Racial Differences in Economic Security: Non-Housing Assets. (2023, August 28). U.S. Department of the Treasury. https://home.treasury.gov/news/featured-stories/racial-differences-in-economic-security-non-housing-assets

[15] Avery, R. B., & Rendall, M. S. (2002). Lifetime Inheritances of Three Generations of Whites and Blacks. American Journal of Sociology, 107(5), 1300–1346. https://doi.org/10.1086/344840

[16] Aibangbee, Y. (2023, September 30). The Basel Proposal: What it Means for Mortgage Lending. Bank Policy Institute. https://bpi.com/the-basel-proposal-what-it-means-for-mortgage-lending/

[17] Wei Li, Bing Bai, Laurie Goodman, and Jun Zhu, p. 7.

[18] Goodman and Zhu, p. 8.

[19] Additional specifications for the HMDA analysis included no open-end loans, no reverse mortgages, and no loans for property used primarily for business purposes.

[20] Barrett, J. (2023, March 13). Silicon Valley Bank: Why did it collapse and is this the start of a banking crisis? The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/business/2023/mar/13/silicon-valley-bank-why-did-it-collapse-and-is-this-the-start-of-a-banking-crisis

[21] Tennekoon, V. S. (2023, March 14). Analysis: Why Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank failed so fast. PBS NewsHour. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/economy/why-silicon-valley-bank-and-signature-bank-failed-so-fast

[22] Most members of the public would not know that call report data can be accessed via the FFIEC website: https://www.ffiec.gov/infosystem.htm#callTFR

[23] Proposed regulatory capital rule, p. 73.

[24] Wei Li, Bing Bai, Laurie Goodman, and Jun Zhu, NeighborWorks America’s Homeownership Education and Counseling: Who Receives It and Is It Effective? Urban Institute, September 2016, https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/84476/2000950-NeighborWorks-America%27s-Homeownership-Education-and-Counseling-Who-Receives-It-and-Is-It-Effective.pdf

[25] Wei Li, Bing Bai, Laurie Goodman, and Jun Zhu, p. VII in the executive summary.

[26] Li, W., Bai, B., Goodman, L., & Zhu, J. (2016). NeighborWorks America’s Homeownership Education and Counseling: Who Receives It and Is It Effective? [Research Report]. The Urban Institute. https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/2016/09/30/2000950-neighborworks-americas-homeownership-education-and-counseling-who-receives-it-and-is-it-effective.pdf

[27] Elizabeth Laderman and Carolina Reid, “CRA Lending during the Subprime Meltdown” in Revisiting the CRA: Perspectives on the Future of the Community Reinvestment Act, eds. Prabal Chakrabarti, David Erickson, Ren S. Essene, Ian Galloway, and John Olson (Federal Reserve Banks of Boston and San Francisco, February 2009), https://www.frbsf.org/community-development/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/cra_lending_during_subprime_meltdown11.pdf, p. 122.

[28] Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, Treasury, the Board of Governors of the

Federal Reserve System, and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, Proposed Rule: Regulatory capital rule: Amendments applicable to large banking organizations and to banking organizations with significant trading activity, https://occ.gov/news-issuances/news-releases/2023/nr-ia-2023-80a.pdf, pp. 325-327.

[29] Consumer Finance Protection Bureau, Final Rule, Qualified Mortgage Definition under the Truth in Lending Act (Regulation Z): General QM Loan Definition, https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/cfpb_atr-qm-general-qm-final-rule_2020-12.pdf, p. 8.

[30] Kathleen Kraninger. (2020, December 21). Consumer Financial Protection Bureau Issues Advisory Opinion to Help Expand Fair, Equitable, and Nondiscriminatory Access to Credit. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/cfpb_advisory-opinion_special-purpose-credit-program_2020-12.pdf

[31] Andrew P. Scott & Marc Labonte. (2023). Bank Capital Requirements: A Primer and Policy Issues (R47447). Congressional Research Service. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R47447

[32] Rosengren, E. (2013, February 25). Bank Capital: Lessons from the U.S. Financial Crisis. Bank for International Settlements Forum on Key Regulatory and Supervisory Issues in a Basel III World. https://www.bostonfed.org/news-and-events/speeches/bank-capital-lessons-from-the-us-financial-crisis.aspx

[33] Barr, M. S. (2023). Review of the Federal Reserve’s Supervision and Regulation of Silicon Valley Bank. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/files/svb-review-20230428.pdf

[34] Son, H. (2023, March 28). SVB customers tried to withdraw nearly all the bank’s deposits over two days, Fed’s Barr testifies. CNBC. https://www.cnbc.com/2023/03/28/svb-customers-tried-to-pull-nearly-all-deposits-in-two-days-barr-says.html

[35] Barr, M. S. (2023). Review of the Federal Reserve’s Supervision and Regulation of Silicon Valley Bank. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/files/svb-review-20230428.pdf