Statement of the National Community Reinvestment Coalition

U.S. House Committee on Financial Services

Subcommittee on Housing, Community Development and Insurance

May 8, 2019

Chairman Clay, Ranking member Duffy and members of the Subcommittee on Housing, Community Development and Insurance:

The National Community Reinvestment Coalition (NCRC) commends you for holding this review on the state of and barriers to minority homeownership and we are pleased to submit this statement for the record of today’s hearing.

NCRC and its more than 600 grassroots members include community reinvestment organizations; community development corporations; local and state government agencies; faith-based institutions; community organizing and civil rights groups; minority and women-owned business associations, as well as local and social service providers from across the nation. We work with community leaders, policymakers and financial institutions to champion fairness and fight discrimination in banking, housing and business. In brief, NCRC member organizations create opportunities for people to build wealth.

We at NCRC recognize that both growing economic inequality and the ongoing racial wealth divide derive from and are perpetuated by regressive public policies. Public policy advancing homeownership and affordable housing to low-wealth Americans are fundamental to maintaining and advancing our country’s middle-class economy. Recently, NCRC has taken two steps to advance our work in addressing affordable housing and asset building. We helped form the Affordable Homeownership Coalitionwith industry stakeholders that include a wide array of organizations – community and civil rights advocacy groups, lenders, home builders, real estate professionals and trade associations. The Coalition is building a broad consensus around a set of national, state and local laws, policies and business practices that enable more families to access affordable homeownership. We are also working throughout all of our departments to strengthen our racial-wealth-divide analysis so our policies and programs can better address the growing challenge of racialized-asset poverty. As part of this effort, we have hired Dedrick Asante-Muhammad, a known and long-time national expert on racial economic inequality, as our new Chief of Equity and Inclusion.

I. Minority Homeownership and Wealth-Building

We at NCRC recognize that no investment is more significant to building wealth for low-wealth Americans than owning a home.

For proof, look no further than the latest edition of the Federal Reserve’s Survey of Consumer Finances which reported that the median net worth of a homeowner was $231,400 in 2016, a 15% increase since its previous survey in 2013. Meanwhile, the median net worth of renters decreased by 5% to just $5,200.[1]

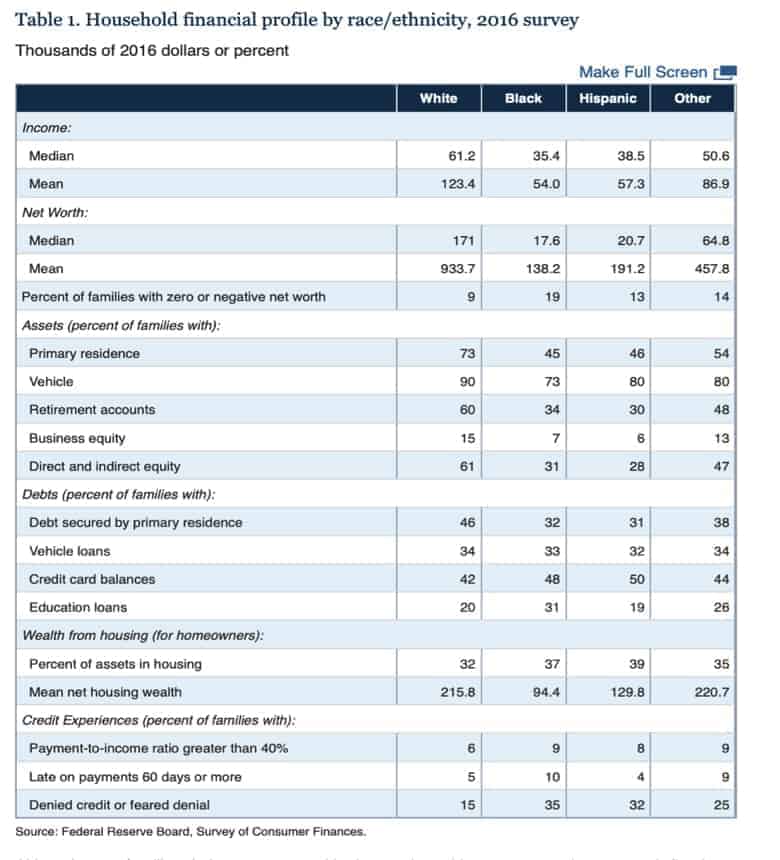

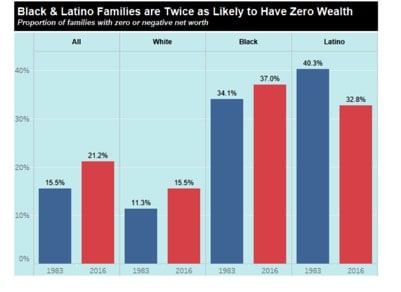

White households already held a significant wealth advantage over minorities, reflected in the huge historic gap in homeownership rates among races. According to the Federal Reserve Board, the net worth of a typical Black family was $17,409 in 2016 compared to $171,000 for a typical White family, a roughly 10-fold difference.[2]

In important research, Demos and the Institute on Assets and Social Policy (IASP) projected the impact that equal homeownership and home appreciation would have on closing the racial wealth divide for African Americans and Latinos.[3] It noted that parity in homeownership for Blacks and Hispanics would increase and help close the racial wealth divide by about $30,000 and that equalizing returns in homeownership would increase Black wealth by another $17,000 and Hispanic wealth another $42,000. Expanding homeownership levels and increasing returns of homeownership for Blacks and Hispanics promises to increase wealth levels many times over.

Rates of homeownership for all races began to climb in 1994 and continued through the mid-2000s. Homeownership rates for Whites and Blacks peaked in 2004 when 76% and 49.1% were homeowners, respectively, a 26.9 percentage-point gap. Hispanic homeowners were one point behind Black homeowners in 2004 but passed them the next year and have continued to widen the gap.[4]

The Great Recession hit many homeowners hard but Blacks and Hispanics far worse. Those borrowers were more likely to have held subprime and predatory loans, suffered from foreclosure and lived in neighborhoods ravaged by vacant and abandoned homes, all of which wreaked havoc on nascent, wealth-building efforts.

Here we are, just a few months away from the longest peacetime economic expansion in our nation’s history and Black and Hispanic families still have yet to see the majority of their populations become homeowners. Hispanic homeownership is only at 46.5% – below its pre-recession level of 48.5% in 2007- and African Americans have a homeownership rate of 41.1%, the lowest since the passage of the Fair Housing Act in 1968. The gap between White and Black homeownership has soared to 32.1 percentage points.[5]

II. The Barriers: The legacy of redlining and modern-day cases

In a 2018 report, NCRC researchers found that economic and racial segregation created by “redlining” persists in many cities.[6] While overt redlining is illegal today, its enduring effect is still evident in the structure of U.S. cities. Part of the evidence of this enduring structure can be seen in the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) maps created 80 years ago, and the economic and racial/ethnic composition of neighborhoods today. The maps were created by the HOLC as part of its City Survey Program in the late 1930s. Neighborhoods considered high risk or “Hazardous” were often “redlined” by lending institutions, denying them access to capital investment which could improve the housing and economic opportunity of residents.

NCRC took these maps and compared the grading from 80 years ago with more current economic and demographic status of neighborhoods as low-to-moderate income (LMI), middle-to-upper income (MUI), or majority-minority. To a startling degree, the results reveal a persistent pattern of both economic and racial residential exclusion. They provide evidence that the segregated and exclusionary structures of the past still exist in many U.S. cities. Descriptive analysis indicated a high degree of correspondence between HOLC high-risk grading of 80 years ago and a persistent pattern of economic inequality and segregation today. A regional analysis showed that the South and West had the highest correspondence for HOLC high-risk grades and majority-minority neighborhood presence, while the South and Midwest had the most persistent economic inequality.

Redlining is not just a matter of is history. In recent years, the CFPB, HUD, and DOJ have settled several multi-million dollar redlining cases.[7] And, this committee recently heard testimony from Aaron Glantz who documented redlining against Black and minority communities in 61 cities as part of his Reveal reporting for the Center for Investigative Reporting.

A. Breaking down redlining and credit access barriers….erecting new ones?

Legislation pending before the Committee make important strides forward by removing some cost barriers in the FHA programs (e.g. The Making FHA More Affordable Act of 2019), establishing basic requirements around land installment contracts and clarifying rules for mortgagors that are DACA recipients (e.g. The Homeownership for Dreamers Act). In addition to acting on new legislative proposals to address existing or longstanding barriers to minority homeownership, the Committee’s oversight and input will be critical as today’s regulators reshape interpretations of current laws in ways that can either mitigate barriers or create new ones.

1. Regulatory rewrite of the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA)

As you know, the bank regulators are considering transformational changes to the regulatory framework for the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) – a remedial statute and a potent Congressional response to redlining. Proposed changes could impact the extent to which the law facilitates homeownership for low- and moderate-income borrowers and communities. How will single-family lending count in a reconfigured CRA exam? Will the CRA exams’ fair-lending reviews be further weakened or strengthened? Will regulators provide CRA examiners better guidance on bank lending that facilitates gentrification or displacement in minority and LMI communities?

Today, CRA examinations cover about 30% of all mortgages. Will regulators define bank assessment areas under CRA in ways that examine more of a bank’s lending – a step that would mitigate CRA grade inflation and help address some barriers to homeownership? Among other provisions designed to remedy historic redlining, H.R. 1737, the American Housing and Economic Mobility Act, would update and expand CRA examinations to more lending and more lenders.

2. Proposed changes to HMDA

The CFPB is currently considering a proposal that could exempt more than half of the nation’s banks from having to report basic information about their mortgage lending and could also require fewer independent mortgage companies and other nonbanks to report Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA) data than before the crisis. The agency could also trim enhanced data added to HMDA reporting by the Dodd-Frank Act and the CFPB’s 2015 rule implementing the law. Both basic HMDA data and enhanced HMDA data not only help regulators and other stakeholders better understand the barriers to homeownership and discriminatory lending patterns, but also helps public officials who use the information to develop and allocate housing and community development investments and to respond to market failures.

3. Housing finance reform on the horizon

The Presidential Memoranda on Housing Finance Reform issued broad directives to nine federal officials calling for a Treasury Housing Reform Plan and a HUD Reform Plan. These plans will inform or reflect Administration policy around Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac’s (the government-sponsored enterprises or “GSEs”) capital requirements, set our parameters around risk management and mitigation at the GSEs and other federal insurance programs, define the interplay between the GSEs and FHA, and overall, put a number of policies in motion that could really redefine how and to what extent LMI borrowers and communities access mortgage credit – borrowers who have access today or who have historically had some access to affordable mortgage credit to purchase and rehabilitate their homes. Important issues around accessibility and affordability on whether guarantee fees and other credit pricing is affordable, the extent of affordable loan products available, allowable debt-to-income (DTI) ratios and more could have real impacts for minority borrowers. The FHFA approach to the GSEs affordable housing obligations (e.g. level of annual affordable housing goals, rigor around Duty to Serve obligations, whether contributions to the Housing Trust Fund and Capital Magnet Fund are made) all play an important role.

III. The Barriers: Income inequality, neighborhood and broader challenges that impede minority homeownership

A family history of owning a home is another key indicator of the prospects for homeownership for young adults, a statistic that tilts decidedly in the direction of White households[8]. The homeownership rate of white millennials is 37 percent, compared with 27 percent for Asians, 25 percent for Hispanics, and 13 percent for blacks.[9] And while 18-to-34-year-old millennials in all racial and ethnic groups have experienced a drop in homeownership since 2005, the homeownership rate among black households headed by 45-to-64-year-olds (who are most likely to be parents of millennials) dropped significantly over the past 15 years.[10] Student debt is also a greater burden on minorities, as well. And, while a college degree generally enhances the possibility to own a home the stark reality is that Black households with a college education are less likely to own a home than White households whose head did not graduate from high school.[11] The factors behind these realities implicate a broader array of issues around income inequality, neighborhood and other barriers that also affect minority homeownership and asset-building.

In groundbreaking research, Harvard University Professor Raj Chetty mapped which neighborhoods in America offer children the best chance to rise out of poverty and found that the intergenerational persistence of disparities varies substantially across racial groups.[12]For example, Hispanic Americans are moving up significantly in the income distribution across generations because they have relatively high rates of intergenerational income mobility. In contrast, Black Americans have substantially lower rates of upward mobility and higher rates of downward mobility than Whites, leading to large income disparities that persist across generations. Conditional on parent income, the Black-White income gap is driven entirely by large differences in wages and employment rates between Black and White men.

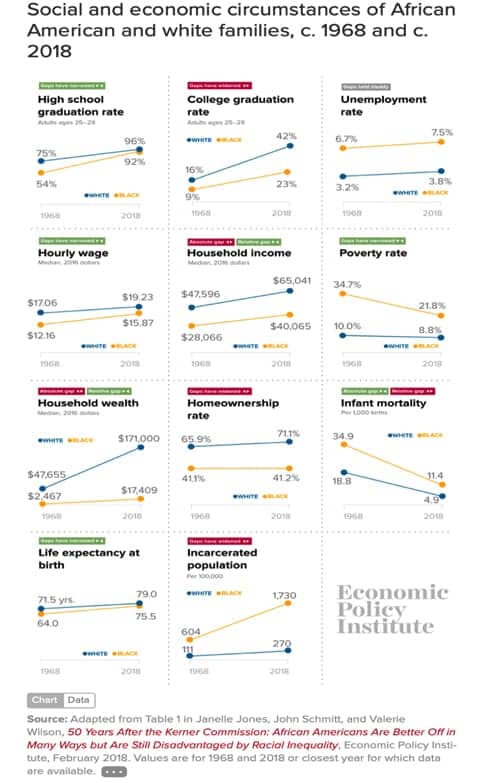

In other work, the Economic Policy Institute’s review of progress 50 years after the Kerner Commission documented in 11 diagrams the continuing racial inequality between Black and White families.

This research, as well as other evidence, tends to all reinforce that earlier interventions, place-based strategies and related approaches are critical to overcoming barriers to minority homeownership and asset-building.

A. Promising approaches on inequality and homeownership…but also policy challenges

A number of new initiatives and proposals are attempting to address a broader array of issues around financial access.

1. Baby Bonds and other possible solutions

The Institute of Policy Studies has proposed, and others have joined in supporting, 10 ways to address the racial wealth divide.[13] Some of these proposals fall within the Committee’s jurisdiction, such as a greater investment in affordable housing. Setting up baby bonds is another solution. They are federally managed accounts set up at birth for children and endowed by the federal government with assets that will grow over time. When a child reaches adulthood, they can access these funds to purchase a home, for example. One recent study shows that a baby bond program has the potential to reduce the current Black-White wealth gap by more than tenfold.[14] Another study shows that had a baby bond program been initiated 40 years ago, the Latinx-White wealth divide would be closed by now and the Black- White wealth divide would have shrunk by 82 percent.[15] Improving data collection on the breadth and scope of the racial wealth divide would also help inform the discussion and policy approaches.

2. Better access to housing counseling

Housing counseling is a very effective way to eliminate barriers for minority families and prepare them for responsible and sustainable homeownership, and loans to home buyers that have received counseling perform better.[16]In FY 2017, 74 percent of housing counseling clients were people of color and 73 percent were LMI households with incomes of 80% of median income or less.[17]H.R. 2162 improves the incentives for home buyers to use housing counseling by linking it to a discount on FHA mortgage insurance premiums, which also makes homeownership more affordable. Given the data about the advantages of parental homeownership, we recommend the sponsors consider adding a deeper discount for first generation home buyers.

3. Opportunity Zones…also challenges

Newly-created Opportunity Zones have created a new vehicle to invest in thousands of underserved communities across the country. Implementation of the program offers an opportunity to facilitate affordable homeownership for minority families, but done incorrectly, it could also facilitate widespread displacement in minority and LMI communities, and particularly in markets already grappling with affordable housing issues and with high levels of socioeconomic change – a proxy for gentrification and displacement risk.[18] Currently, the program has no real statutory data collection or reporting requirements on investments or outcomes. Both HUD and IRS have outstanding proposals on Opportunity Zones and, among other reporting requirements, regulators should track, collect and report data that evinces displacement risk. We urge this Committee to also consider how it might weigh in on Opportunity Zones policy around minority homeownership and affordable housing issues.

IV. Affordable housing inventory and other barriers affecting minority buyers and the broader market

There are a number of housing inventory issues that are inhibiting minority families and LMI families more broadly in their effort to own a piece of the American Dream – a home. NCRC, in conjunction with a number of industry stakeholders, as a part of the Affordable Homeownership Coalition, have identified a number of infrastructure, financing and other barriers, including:

- a historic low in the inventory of affordable homes for sale;

- household formation and demand for homes is outstripping the supply of affordable homes;

- some local zoning, land-use and permitting requirements are making it increasingly difficult to secure land and build homes affordable to LMI households;

- labor shortages and workforce training issues are also roadblocks to affordable homebuilding;

- financing small mortgages – for home purchase and rehabilitation – in large swaths of the country, including many traditionally minority communities, is near impossible;

- home appraisal issues have been identified in a number of minority and LMI communities across the country;

- issues around down payment – the difficulty of saving towards one and access to down payment assistance.

One way to begin to address some of these inequities would be for Congress and the Administration to include select incentives for single-family residential construction and preservation as part of any national infrastructure plan to be considered.

V. Conclusion

We know there are no “silver bullets” to solve these vexing problems. Moreover, the crisis of affordable homeownership for minority and LMI families cannot be solved at the federal level alone, but must also find supporters in state and local governments who are eager to address existing barriers. It is why we are prepared to take our fight not only here to Capitol Hill but to statehouses and city halls throughout the nation so that the American Dream of homeownership can be a reality for families too often left behind.

The challenges of increasing access to affordable homeownership for the nation’s minority households, including eliminating existing barriers and defeating policies that could erect new ones, are considerable. But the risks to the social and economic well-being of the country of ignoring those challenges are even greater.

The nation can’t afford to fail in this effort. To do so would consign a generation of involuntary renters to a future free from financial security and hope for a better life and a racial wealth gap that could widen further. Rather, the country must do the hard work to create more affordable homes and more minority homeowners. A fairer and more prosperous nation awaits when we succeed.

[1] “Changes in U.S. Family Finances from 2013 to 2016: Evidence from the Survey of Consumer Finances,” Federal Reserve Bulletin, Sept. 2017, vol. 103, number 3, p. 13

[2]Recent Trends in Wealth-Holding by Race and Ethnicity: Evidence from the Survey of Consumer Finances, FedNote, Sept. 27, 2017. In 2016, White families had the highest level of both median and mean family wealth: $171,000 and $933,700, respectively. Black and Hispanic families have considerably less wealth than White families. Black families’ median and mean net worth is less than 15 percent that of White families, at $17,600 and $138,200, respectively. Hispanic families’ median and mean net worth was $20,700 and $191,200, respectively.

[3]“The Racial Wealth Gap: Why Policy Matters”Demos and IASP, 2015.

[4]U.S. Census Bureau, “Housing Vacancies and Homeownership” surveys

[5]U.S. Census Bureau, “Quarterly Residential Vacancies and Homeownership” survey for First Quarter 2019, April 25, 2019. NCRC has also found that the gap in Black and White homeownership has averaged 25 percent for 119 years. The gap has never been smaller than 22 percent and now stands at its largest at 32 percent.

[6]HOLC “REDLINING” MAPS: The persistent structure of segregation and economic inequality, NCRC, March 20, 2018.

[7]BancorpSouth entered a $10.6 million consent order with the CFPB and the DOJin 2016; Hudson City Savings Bank settled for $27 millionin 2015; DOJ entered a $9 million settlement with Union Savings Bank and Guardian Savings Bank in 2016; DOJ entered a settlement with Eagle Bank and Trust in 2015 to name a few.

[8]How your parents affect your chances of buying a home, Washington Post, May 4, 2016. See more at:

[9]Is homeownership inherited? A tale of three millennials, Urban Institute, August 2, 2018.

[11]Laurie Goodman and Christopher Meyer, “Homeownership and the American Dream,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, vol. 32, no. 1, January 2018, p. 32

[12]These findings suggest that reducing the Black-White income gap will require efforts whose impacts cross neighborhood and class lines and increase upward mobility specifically for Black men. See Opportunity Insights, Race and Economic Opportunity in the United States: An Intergenerational Perspective, Working Paper, March 2018.See also, See also, Black men face economic disadvantages even if they start out in wealthier households, new study shows, PBS Newshour, March 21, 2018.

[13]Dedrick Asante-Muhammad, Chuck Collins, Darrick Hamilton, Darrick Hamilton, Josh Hoxie,Ten Solutions to Bridge the Racial Wealth Divide, ISPS, April 2019.

[16]See, e.g., Neil S. Mayer & Kenneth Temkin, Pre-Purchase Counseling Impacts on Mortgage Performance: Empirical Analysis of NeighborWorks America’s Experience (p. iii) (March 7, 2013); Marvin M. Smith et al., The Effectiveness of Pre-Purchase Homeownership Counseling and Financial Management Skills (April 2014); and, https://www.huduser.gov/portal/sites/default/files/pdf/Housing-Counseling-Works.pdf

[17]National Housing Resource Center and HUD FY 2017 9902 Housing Counseling Data.

[18]See more at: 2019 NCRC Policy Agenda, p. 40, Issue: Encourage Responsible Investment in Opportunity Zones & Robust Data Collection, Including on Outcomes