On a balmy Friday evening in the nation’s capital, Joe Talbot, Jimmie Fails, Tichina Arnold and Rob Morgan held the D.C. premiere of their newest endeavor, The Last Black Man in San Francisco. The movie, based partially on the life story of the lead actor Fails, is a story of friendship, love of a city and gentrification (with other struggles peppered in), combining for a beautiful, yet powerful, message of what many people of color are experiencing in America’s largest cities.

I was fortunate to be invited to the premiere, which could not have been held at a more perfect location. The Oprah Winfrey Theater at the National Museum of African American History and Culture was filled that night with a crowd as diverse as D.C. There wasn’t an empty seat and soon there wasn’t a dry eye either.

The movie, co-written by childhood friends and Bay-area residents Talbot and Fails, opens with a powerful message – environmental justice is often racial justice. As an African American preacher stands on a milk crate on the outskirts of the city, preaching to a crowd of two – main characters and best friends Jimmie and Mont – people in orange hazmat suits clean the area. The preacher asks, “Why are they in those suits, when we are expected to walk around here every day?”

And the powerful messages keep coming throughout the entire two hours. There are the stares the two men receive from obvious newcomers to the city as they travel through the heart of San Francisco, making them feel like outsiders in the city they grew up in. The group of young black males who hang out on the sidewalk in front of Mont’s house and whose own complexities and expressions of masculinity complicate the more common one-dimensional character development of black men and add to the poetry of the place they are from. The play put on by Mont where he chides the audience for putting people into “boxes,” because “people aren’t one thing.”

And then there is the house. A beautiful Victorian representing all that San Francisco architecture is supposed to be. Jimmie grew up in the house, which according to family lore was built by his grandfather in 1946 when he migrated from New Orleans. As the story goes, his grandfather wasn’t comfortable moving into a home left vacant after the Japanese Americans were rounded up and shipped to internment camps, so he built his own.

Although Jimmie’s family lost the house many years earlier to a white couple, – causing a division amongst family members, Jimmie and Mont still visit it regularly so Jimmie can care for it. The white owners don’t meet Jimmie’s standards of care, so he tenderly and intricately tends to the gardens and paints the trim. It is as if the house is tied to Jimmie’s identity and future.

And then he gets his chance. The owners move out, leave it vacant and Jimmie and Mont move in. The two friends spend hours restoring and reveling in it. But no vacant house worth $4 million will go unnoticed for long, and just as soon as Jimmie regains his spirit from having his childhood home back, he is lost again. Because even though Jimmie has a good job as a night nurse in a nursing home, the white bank lender ignores his request for a loan, forcing Jimmie to face the reality that the house and city he grew up in and loved his entire life no longer have a space for him.

Forced out – a reality for many black people in San Francisco. The statistics are alarming. In the 1970s, about one in seven residents was black. Today, it is more like one in 20.

However, it isn’t just African Americans, but rather all working class people. San Francisco has one of the largest disparities between rich and poor in the country, resulting in big changes in its charm and culture, according to the co-writers.

Those changes are not unique to San Francisco. Before the screening, there was a reception on the fifth floor of the museum overlooking the Mall and all the monuments that line it. A breathtaking view made even more poignant by the sounds of go-go music streaming up from a party on the Mall. Listening to go-go, a staple of D.C. black culture, was a reminder of the city’s own struggle with gentrification.

In a recent report from the National Community Reinvestment Coalition, D.C. was found to be the city with the most gentrifying neighborhoods in the country between 2000 and 2013. And just this past spring, after the report was released, gentrification was at the heart of a confrontation over go-go music being played at a storefront street corner. The store owner won, and for now, the music plays on.

[pexyoutube pex_attr_src=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C0FnJDhY9-0″ pex_attr_width=”700″][/pexyoutube]

Alyssa Wiltse-Ahmad is a social and environmental justice writer and editor, who currently serves as media manager for NCRC.

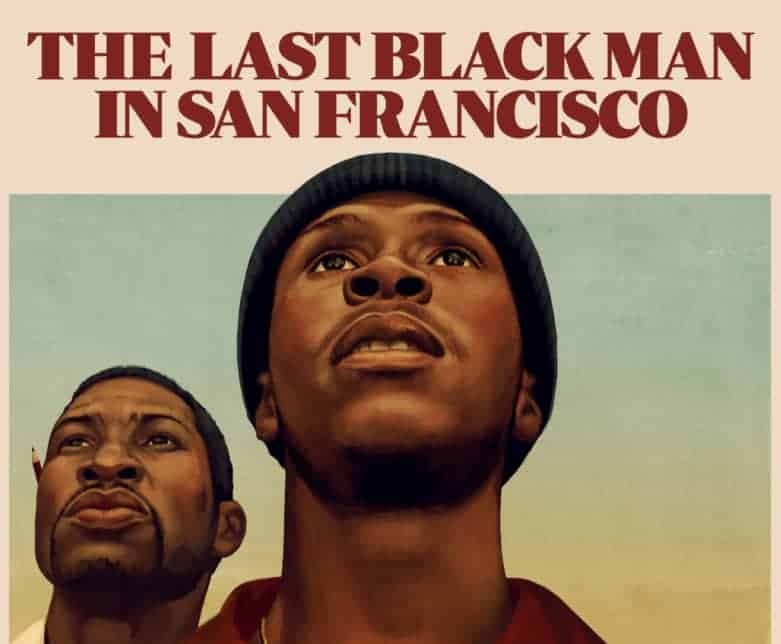

Top Image from A24