August 24, 2022

Kathy L. Moe

Regional Director

Janet R. Kincaid

Deputy Regional Director

Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation

25 Jessie Street at Ecker Square, Suite 2300

San Francisco, CA 94105

Re: Interagency Charter and Federal Deposit Insurance Application for Ford Credit Bank, a Utah State-Chartered Industrial Bank, Submitted to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation and the Utah Department of Financial Institutions

Dear Deputy Regional Directors Moe and Kincaid:

Please accept this comment on the application for deposit insurance from Ford Motor Company (“Ford Motor”) as a part of its charter application to establish the Ford Credit industrial loan company.

The National Community Reinvestment Coalition and its grassroots member organizations create opportunities for people to build wealth. We work with community leaders, policymakers, and financial institutions to champion fairness and end discrimination in lending, housing, and business.

Since 1969, the nonprofit National Consumer Law Center® (NCLC®) (on behalf of its low income clients) has worked for consumer justice and economic security for low-income and other disadvantaged people in the U.S. through its expertise in policy analysis and advocacy, publications, litigation, expert witness services, and training.

Americans for Financial Reform is a nonpartisan and nonprofit coalition of more than 200 civil rights, consumer, labor, business, investor, faith-based, and civic and community groups. Formed in the wake of the 2008 crisis, we are working to lay the foundation for a strong, stable, and ethical financial system – one that serves the economy and the nation as a whole.

The Center for Responsible Lending is a non-partisan, non-profit research and advocacy organization working to promote financial fairness and economic opportunity for all, end predatory lending, and close the racial wealth gap.

We call on the FDIC to reject this application. Granting deposit insurance to this applicant creates a dangerous mix of commerce and banking, would permit a charter to an entity that has not made a community reinvestment commitment that is commensurate with its size and would create the grounds for a Big Tech data surveillance operation to break the barriers meant to protect consumer privacy.

I. The industrial loan company charter framework creates a dangerous mix of commerce and banking.

- Ford Credit is a source of strength for the parent company, not the other way around, as the FDIC requires.

- Ford Motor’s motives to obtain an ILC charter are distinct from its ability to produce EVs

- This application poses concerns for safety and soundness.

- Ford Credit is already a successful enterprise that fulfills its role of supporting the operations and profitability of Ford Motor Company.

II. Ford Credit’s community reinvestment plan is inadequate. The benefit conferred to Ford Credit by a charter would not be commensurate with the de minimis benefit to the public

- Ford Motor is already committed to the electrification of its car fleet; the decision to use that activity as a core component of its community reinvestment plan is disingenuous.

- The number of hours in its community volunteering plan is too low.

- The size of its commitment is not commensurate with the extent of the proposed ILC.

- The proposed set of business activities is inconsistent with the definition of a limited-purpose bank.

III. ILCs, by nature, are a threat to privacy. An ILC for an automaker will represent an extreme example of those conflicts.

- Ford Motor EVs are connected devices that can download and upload data. Consumer data is shared between Ford Motor and Ford Credit. Information is sold to third parties. Incursions on consumer privacy match the standard practices of Big Tech firms.

- Sharing occurs between Ford’s credit and commerce sides, with third-party affiliates, social media platforms, government agencies, and for collecting debts.

DISCUSSION

I. The industrial loan company charter framework creates a dangerous mix of commerce and banking.

In the United States, bright lines have existed to separate banking from commerce. The industrial loan charter is a problematic contradiction to that principle. If Ford Credit received an ILC charter, regulators would have little insight into its corporate parent’s operations even though they have many interdependent relationships.

The FDIC should be skeptical of tie-ups in this business sector. Automobile manufacturers rely on captive financing divisions to support retail sales. While the benefit of lower-cost deposits as a substitute for commercial debt and equity financing benefits manufacturers, it increases the interdependence between financing and manufacturing divisions, leading to correlated risks that undermine safety and soundness. Automobile manufacturing is a highly cyclical industry whose history demonstrates that it can lose money during recessions.

a) Ford Credit is a source of strength for the parent company, not the other way around, as the FDIC requires.

In its December 2020 final rule, the FDIC stated that it would ensure that a parent company is a “source of strength” to the covered industrial loan company.[1]

Ford Motor is supposed to be a “source of strength” for Ford Credit. However, the opposite tends to be true – Ford Credit is more likely to be a source of strength for Ford Motor itself because the sales and leasing of new cars are far more volatile than the performance of multi-year car loans and leases.

Table: Ford Credit is a source of strength for the parent company.

| Ford Automotive (operating) | Non-operating | Ford Credit | Dividends paid to shareholders | |

| 2021** | $13.4 | Not broken out | $4.51 | $0.40 |

| 2020* | 2.07 | $(4.31) | 1.92 | 0.60 |

| 2019* | 4.45 | (5.72) | 2.23 | 2.39 |

| 2018* | 4.70 | (2.73) | 2.22 | 2.91 |

| 2017 | 4.89 | (0.21) | 2.94 | 2.58 |

| 2016 | 6.31 | (3.02) | 1.32 | 3.4 |

Profit (loss) in billions of dollars. * Figures exclude the costs of the new mobility segment **mobility segment integrated within the automotive segment. Financial information is sourced from Ford’s Annual Reports.

In 2020, the auto desk at the Detroit News summarized the relationship between Ford Motor and Ford Credit: “Ford Credit, the lending arm that’s become accustomed to propping up the company in good times and bad, now generates about half the automaker’s profit, up from 15% to 20% in the past…The second-largest US automaker would be far worse off without its Ford Motor Credit Co. unit, effectively funding turnaround efforts by routinely borrowing in the debt markets and paying a dividend back to the parent company.”[2]

Before the pandemic, Ford Motor used profits from Ford Credit to pay its dividend. As a general rule, de novo banks are not supposed to pay dividends to shareholders. The deposit insurance application states that shareholders will not receive dividends.

Nonetheless, profits from Ford Credit are necessary for the ongoing financial stability of Ford Motor. Without earnings from Ford Credit, Ford Motor lost money in 2018, 2019, and 2020. Without funds from Ford Credit, Ford Motor would have had to seek additional external financing to pay its dividends in 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019, and 2020.

The possibility exists that even if shareholders did not receive a dividend from Ford Credit, the capital position of Ford Credit could be weakened by claims from outside parties for its profits. Ford Credit is the only shareholder in Ford Credit Bank. So, while Ford Credit Bank shareholders may not receive dividends – which would be sensible for a de novo institution – Ford Credit may have to devote at least a share of its profits to an independent entity. True, if Ford Motor is profitable enough, it will have cash flows to support its dividend from operations. However, if it is not, the firewall between Ford Credit and Ford Motor will have deleterious effects on the financial health of Ford Motor. A tie-up of this sort goes against the separation of banking and commerce and also undermines the FDIC’s rule that corporate parents should be a source of strength to the ILC.

b) Ford Motor’s motives to obtain an ILC charter are distinct from its ability to produce EVs.

Ford Motor has repeatedly tried to obtain an ILC, long before its commitment to manufacture EVs.[3] Access to credit for households or auto dealerships will not influence the transition to electric vehicles (EVs), but instead will provide cheaper wholesale financing for Ford. The key challenges in transitioning to an electric fleet are ones of battery supply and supply chain.

Additionally, through the ongoing provision of federal tax credits and new electric transportation provisions in the Inflation Reduction Act, Congress and the Biden Administration have supported auto manufacturers in their pursuit of the transition to EVs.

However, the FDIC should not permit an automaker to leverage a shift in strategic operations to secure the privilege of having a bank charter, and instead view this new messaging as the latest ploy to achieve a long-desired goal of Ford Motor.

Moreover, some claims that Ford Motor’s EV transition will benefit America’s economy are only half-truths. Ford Motor’s EV-related strategic initiatives still rely on supply chain inputs outside the United States. It has announced agreements to purchase nickel with producers in Canada and Indonesia and to source lithium from Brazil. It will buy batteries from China and build battery packs in Mexico. All commitments to on-shoring are non-binding MOUs. [4] To underscore the zero-sum nature of Ford Motor’s strategic direction, earlier this week Ford Motor announce plans to cut 3,000 salaried and contract jobs as part of its shift away from internal combustion engines.[5]

c) This application poses concerns for safety and soundness.

Ford Credit depends on numerous aspects of the attractiveness to consumers of Ford cars and trucks: “Though Ford Credit’s access to Ford’s dealers and retail customers provides it the opportunity to originate sizeable new retail loan volumes, its Ford product and dealer business concentrations expose it to Ford’s performance trends.”

For example, the profitability of Ford Credit’s leasing division (and the valuation of its asset-backed securities composed from lease contracts) deteriorates if leased cars depreciate at faster-than-expected rates, as the leasing model depends on Ford Credit’s ability to sell used vehicles to other buyers when they are returned at the end of their lease period.

The profitability of Ford Motor correlates with risks to Ford Credit because the performance of auto loans mirrors the cyclicality of the broader economy. Demand for new cards rises and falls in sync with the financial health of American households. Similarly, Ford Credit performs well when there is high employment and households have positive cash flows. The same fidelity means that default rates rise during downturns.

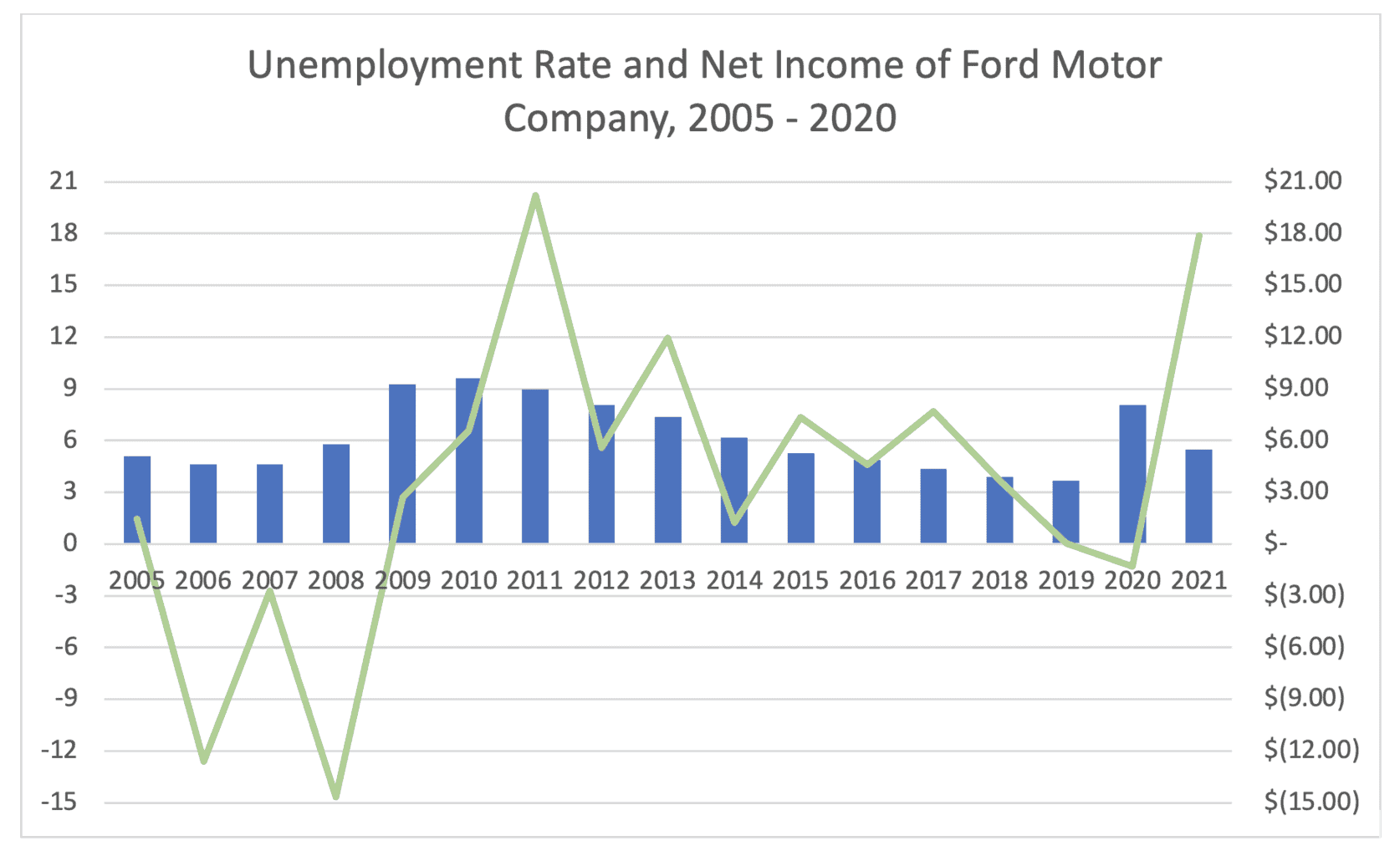

Chart: Domestic sales of cars and trucks in the US and Net Income of Ford Motor Company, 2005 – 2020

Left axis: US Unemployment Rate. Right Axis: Net income (loss) in billions of dollars, Ford Motor Company Annual Reports.

The table above highlights the cyclicality of Ford Motor’s business and shows how the company’s profits rise and fall with the state of the workforce. The high degree of change in the company’s profits and its consistent correlation with broader trends in the company underscores the risk in the corporate parent of the applicant.

ILCs have a demonstrated record of failure. These problems have occurred consistently across many periods. Twenty-one ILCs failed before 2004.[6] During the financial crisis, several ILCs failed or came close to failure. General Motors Acceptance Corporation, an ILC that provides car loans for General Motors, transferred from ILC status to a bank holding company structure and later received $17 billion in Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) funds to rectify its balance sheet. Other ILCs also received TARP relief.[7]

In 2008, Ford Credit reported $2.6 billion in losses. The poor performance of Ford Credit coincided with fundamental problems at Ford Motor. The immediate decline in sales at the outset of the pandemic, before the federal government intervened with financial relief, underscores how quickly the fortunes of an automotive manufacturer can suffer from a downturn in the economy. Sales of cars and trucks fell 23 percent in March 2020 compared to the month before, but after state and federal governments distributed relief payments, sales rose 39 percent.[8]

By some accounts, Ford Credit drives the profitability of Ford Motor itself. In 2020, profits from Ford Credit made up approximately half of profits across the entire company. Credit rating agencies are skeptical of the company’s long-term horizon, as evidenced by its loss of an investment grade rating in 2020. Moody’s rates Ford’s senior unsecured debt at Ba2 – two tiers below the minimum threshold of investment grade status.

d) Ford Credit is already a successful enterprise that fulfills its role of supporting the operations and profitability of Ford Motor.

We do not see grounds to support the claim that the approval of an ILC charter for Ford Credit will lead to benefits to the public. In any measure, Ford Credit fulfills the needs of Ford Motor at an enormous scale and earns a consistent and substantial profit.

In its “detailed credit considerations” of Ford Credit’s bonds, an analyst at Moody’s emphasizes the foundational contribution that Ford Credit already contributes to the profitability of its corporate parent. “Ford Credit’s franchise position is based upon its utility in helping its parent Ford to sell more vehicles. Its activities include offering loans and leases that provide liquidity and support to buyers of Ford’s products. Ford Credit’s strategic importance to Ford is in particular demonstrated by the critical inventory financing the company provides to Ford’s dealers.”

The comment of this analyst underscores how non-bank Ford Credit already meets the credit needs of Ford Motor.

Ford Motor has no liquidity problem because it can access incredible funding from corporate bond markets. It can receive billions of dollars in financing by issuing corporate bonds, notes, and commercial paper. When Ford Motor needed to invest $11.4 billion in EV infrastructure in 2021, it immediately sold new debt. In March of 2021, it took advantage of low interest rates to sell $2 billion in convertible zero-coupon bonds to pay down some of its existing debt. In September, it completed a transaction to secure a $15.5 billion revolving line of credit. The latter was the most significant “green” credit facility ever. In November, it used some of that new debit to pay down another $5 billion in outstanding debt that it had issued at a higher rate in 2020. Then, in the same month, Ford sold another $2.5 billion “green” bond, whose proceeds were used for investments in EV and EV networks, and at a premium to par.[9]

At the end of 2021, Ford Credit held $12.9 billion in “retail deposits.”[10] It takes uninsured deposits through its Ford Interest Advantage (FIA) program. The FIA prospectus calls the investments a floating rate demand note. Ford Credit promises to pay at least 25 basis points above the average yield of taxable money funds.[11]

Ford Credit reported returns on equity of 15 percent in 2020 and 32 percent in 2021.[12]

II. Ford Credit’s community reinvestment plan is inadequate. The benefit conferred to Ford by a charter would not be commensurate with the de minimis benefit of its community reinvestment plan to the public.

a) Ford is already committed to the electrification of its car fleet; the decision to apply that activity as a core component of its community reinvestment plan is disingenuous.

Receiving a charter is not a necessary step for Ford Motor to realize its intentions to shift to an all-EV product lineup. As mentioned above, Ford has already secured the financing to pay for its transition toward sustainable manufacturing. Yet Ford dares to suggest that there is a quid pro quo: if it receives a charter, it will confer the benefit of green enterprise on the public.

Ford Motor will move to electrification with or without a charter. In its 2022 Annual Report, the company states:

“Ford has announced its intent to continue making multi-billion-dollar investments in electrification and mobility. Ford’s plans to manufacture electrified versions of many of its vehicles, including the F-150 Lightning and E-Transit. If the market for electrified vehicles does not develop at the rate Ford expects, even if the regulatory framework encourages a rapid adoption of electrified vehicles, there is a negative perception of Ford’s vehicles or about electric vehicles in general, or if consumers prefer its competitors’ vehicles, there could be an adverse impact on Ford’s financial condition or results of operations.”[13]

Ford Motor has already built NA’s most extensive public charging network (“BlueOval Charge”) with 70,000 charge plugs and Ford Pro Charging for software for fleets. But BlueOval Charge (BOC) is a service provided exclusively to owners of Ford cars and trucks. While buyers may receive initial discounts on using the BOC network, there are subsequent costs. Its Electrify America partner also charges 43 cents per kilowatt – much higher than the national average for kilowatts at home.

These announced plans demonstrate that green investment is already on the table. That leaves an essential question: What additional benefits will Ford confer to the public to justify a charter?

Ford Credit has not claimed it will provide special auto lending programs to underserved communities because that is not a likely outcome. As long as the company packages its loans into asset-backed securities, it will take its directives for how it underwrites its retail auto installment loans from the preferences of those investors. The other use for credit is to create liquidity for dealerships that hold cars on inventory. New car dealerships are not the kinds of small businesses for whom the CRA was intended to support. Instead, they are among the most profitable and highest-revenue companies in many communities. In 2021, the average new car dealership made more than $7 million in profits.[14] The Hendrick Automotive Group, a nationwide set of dealerships, reports revenues of $1.9 million per employee.[15]

Similarly, the primary source of Ford Credit’s demand deposits will come from Ford’s network of auto dealerships. It will attract time deposits by issuing certificates of deposit. The former will certainly not meet goals for financial inclusion, whereas the latter is at best indifferent and most likely somewhat exclusive of reaching low-wealth households. Most of the market for CDs will come from commercial investors. Ford may also use its charter to hold brokered deposits.

b) The number of hours in its community volunteering plan is too low.

As a component of its plan, Ford Credit has promised that its Salt Lake employees will volunteer for between 7 and 10 hours per year. If a bank counts volunteer activity as an element of its community reinvestment plan, it should commit to more than one day of volunteer work per year. Consistent with how Ford has sought credit for green investments that it would have done, its plans to use volunteer hours are another instance of work that would have occurred without a charter. Ford’s Volunteer Corps already engage with communities in low-income schools and health care clinics.

c) The size of its commitment is not commensurate with the extent of the proposed ILC.

Ford Credit is a non-bank with assets of $139.4 billion at the end of 2021. It holds over $10 billion in cash and $92.4 billion in receivables from outstanding retail installment loans, dealer financing, and leases.[16] If Ford Credit’s assets were held in the proposed Ford Credit Bank, the new entity would become, by asset size, the 26th largest FDIC-insured institution in the US and the country’s largest industrial loan company.

Despite that potential size, Ford Credit has proposed performance goals of either $56 million or $74 million in community development loans and investments across its assessment areas (AA), including its broader regional service area (BSRA) and designated disaster areas (DDAs). The first figure corresponds to their proposed performance for a “Satisfactory” grade. The latter would, in Ford Credit’s plan, deserve an “Outstanding” grade. As a percentage of its assets, the 2024 goal for an outstanding rating would be approximately 1/10th of 1 percent of assets.

Table: Ford Credit Goals for CD Lending and Investments in AA, Broader Service and Regional Area, and Designated Disaster Areas

| Year 1 (2024) | Year 2 (2025) | Year 3 (2026) | |

| Outstanding | $13.08 | 25.022 | 36.206 |

| Satisfactory | 10.039 | 19.203 | 27.786 |

$ in millions

Those numbers are minimal inside the context of Ford Credit’s financing activities.[17] As mentioned, Ford Credit earns billions of dollars in profit every year – more than most regional banks. In 2021, Ford Credit reported earnings of $4.51 billion. Some of the largest banks in Michigan earned far less: Fifth Third earned $2.67 billion,[18] Comerica earned $1.12 billion,[19] and Flagstar Banker earned $533 million.[20] Ford Credit is larger and more profitable than all of these banks. Yet, it proposes a community reinvestment plan of a smaller scope, with fewer financial commitments, and across a narrow assessment area.

d) The proposed set of business activities is inconsistent with the definition of a limited-purpose bank. Ford Credit should expand its community reinvestment plan to reflect the scope of the proposed business plan.

In addition to the disconnect between the potential size of Ford Credit Bank and its commitment to community development activities, Ford is also seeking to limit the scope of other types of reinvestment programs. Ford Credit is applying as a limited-purpose bank.

Ford Credit’s activities do not fit the narrow definition of a limited-purpose bank. Limited-purpose banks are monoline entities that perform a single function. For example, credit card banks do not take deposits and only extend a single form of credit. Banker’s banks act as correspondents to meet the payments needs of small financial institutions that would prefer to outsource their payments activities. Similarly, wholesale banks do not provide loans or take deposits from retail households.

Limited-purpose banks are evaluated solely for their community development lending, qualified investments, and community development services.[21]

In its application for deposit insurance, Ford Credit says that it will take deposits, issue retail consumer installment loans, and lease contracts, and provide floor plan credit to dealerships. It will take deposits from consumers and dealerships. It will offer negotiable order of withdrawal (NOW) accounts, savings accounts, and certificates of deposit. It may also arrange to hold brokered deposits from other financial institutions. Ford Credit will not have a limited purpose. Moreover, as mentioned earlier, Ford Credit will be a large financial institution.

It would be ironic if the moment when an interagency effort to modernize CRA introduced auto loans into examinations, the second largest automotive lender in the country received a charter and launched a community reinvestment plan that did not consider auto lending in its CRA plan. By applying as a limited-purpose bank, Ford Credit has sought to exploit that loophole. Instead of considering the allocation of credit in its consumer auto lending portfolio of $69.3 billion,[22] the application wants to emphasize the impact of $74 million in community development activities over three years.

Ford Credit’s application does not provide for an adequate community reinvestment exam. An application from a bank of this size and with this set of activities should be full scope. The FDIC must evaluate Ford Credit under a full-scope evaluation for lending, investments, and services if its deposit application is approved. As is, the poor community reinvestment plan should be grounds to deny the application.

III. ILCs may pose a threat to privacy. An ILC for an automaker will represent an extreme example of those conflicts.

a) Ford Motor EVs are connected devices that can download and upload data. Consumer data is shared between Ford Motor and Ford Credit. Ford sells this information to third parties. Incursions on consumer privacy match the standard practices of Big Tech firms.

To facilitate software updates, Ford Motor must have the ability to connect with individual cars. This singular aspect of EV cars creates an entry point into an entirely new relationship between car drivers and manufacturers. It has also fostered a wholly new set of business opportunities. Ford calls its program “Always On” because it gives Ford Motor a chance to have a continuous relationship with its customers, rather than one that goes dormant between car purchases.

While consumers derive benefits from connectivity, primarily by the ability to receive software updates and transmit information for diagnostics, in other aspects, those opportunities pit the interests of car manufacturers against the privacy of their customers. However, few consumers may understand the scope of data collection and sharing that comes with using an EV.

Ford Credit’s privacy policy details some of the information that it collects through factory-installed connective technology:

- Driving data: Information about a consumer’s driving habits (speed, use of accelerator, brakes, steering, and use of seat belts).

- Vehicle geolocation: Precise location/GPS information about the vehicle, including current location, travel direction, speed, charging locations used (if applicable), and information about the environment where the vehicle is operated (such as weather, road segment data, road surface conditions, traffic signs, and other surroundings).

- Audio/visual: Voice commands and other utterances are captured when the vehicle’s voice recognition system is in an “active listen” state.

- Media analytics: Information about what is listened to in the vehicle (such as radio presets, volume, channels, media sources, title, artist, and genre).

- Vehicle analytics: How drivers use vehicle features, services, and technology.[23]

These incursions mirror the surveillance procedures with services like Amazon’s Alexa or an intelligent home machine.

b) Sharing occurs between Ford’s credit and commerce sides, with third-party affiliates, social media platforms, government agencies, and for collecting debts.

Because ILCs are state-charted institutions that may not be defined as banks by the Bank Holding Company Act (BHCA), their corporate parents are not supervised by the Federal Reserve as bank holding companies (BHCs). Without the requirement to register, the Federal Reserve cannot enforce the limits on data sharing that it does for BHCs under Regulation V (Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act). The Federal Reserve can ask the FDIC, as the “functional regulator,” to supervise corporate parents akin to the supervision of BHCs, but this is not a practice.[24]

Ford Motor shares information between its corporate parent and Ford Credit. For example, if a Ford Credit customer falls into default, it can ask Ford Motor to share the vehicle’s location. Moreover, Ford uses a single sign-on, so all information captured by a Ford Credit account can be shared with Ford Motor.

- Ford Motor shares information with third-party businesses. For example, in disclosing its privacy policies, Ford Motor notes that it shares contact information with Sirius XM.

- Ford Motor shares information with social media platforms. Ford Motor provides data from its marketing database to Facebook. Facebook uses that information to make inferences about Ford Motor customers through its Custom Audiences services. Ford Motor uses Facebook’s Custom Audiences service to place targeted Facebook ads to vehicle owners.

- Ford Motor shares information on a consumer’s car’s features and maintenance history with insurance companies, auction houses, potential purchasers, and analytics firms.

- Through an online account, Ford Motor places cookies on consumer browsers to track their online activities.

- Ford reserves the right to report consumer information to law enforcement agencies, courts, and regulators.

Ford denies responsibility for any harm a consumer might experience due to the activities of a third party with which it has shared information.

Ford Motor and Ford Credit can share data across their respective platforms. For example, Ford Motor will be able to collect information about a person’s driving habits, their geolocation, and their use of in-vehicle “infotainment.” They can use this information to make assessments of a driver’s behavior and to draw conclusions on their suitability for products and services. They can use this information for their purposes – such as to determine the risk of offering a new lease to a driver with known risk-taking habits – or sell it to third parties. Recently, “vehicle data hubs” have emerged that collect data from cars and integrate it with other sources in saleable formats. Data may be purely operational – such as the temperature of the car cabin or if the driver uses a seat belt – but it can also reveal inferences about shopping habits. Geolocation data – such as time spent parked at Whole Foods or the payday lender – is created in real-time and all the time.

Third-party corporations desire this information. Some companies that buy telematics data include Sirius XM, Allstate, Farmers Insurance, Xevo, Geico, and Telenav. Some data is sold on a subscription basis for real-time use cases. For example, Telenav uses data to support “in-car commerce.”[25]

CONCLUSION

We call on the FDIC to deny this application. Our comment highlights the wide range of reasons to support this decision. Recent historical examples demonstrate the risks of providing charters to commercial firms that offer credit for retail auto loans and dealer services. By granting deposit insurance, a necessary condition of charter approval, the FDIC would introduce risk to the banking system. Moreover, Ford Credit has put forth a community reinvestment plan that is wholly inadequate given its size and under the definition of a limited-purpose bank whose model guidelines it does not meet. Lastly, this is another example of a “Big Tech” applicant that, if permitted access to the banking system, would implement privacy practices that undermine the interests of consumer confidentiality.

NCRC believes the ILC charter is a loophole that facilitates dangerous interdependencies between commerce and banking. This application puts those concerns in clear and stark detail. The FDIC must deny this application for deposit insurance.

If we can answer additional questions or provide any clarifications to these comments, please reach out to Adam Rust (arust@ncrc.org) or me directly.

Sincerely,

Jesse Van Tol

Chief Executive Officer

National Community Reinvestment Coalition

[1] Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. (2020). Final Rule: Parent Companies of Industrial Banks and Industrial Loan Companies [Fact Sheet]. https://www.fdic.gov/news/fact-sheets/ilc-12-15-20.pdf

[2] Kevin Naughton, & Molly Smith. (2020, February 3). Ford’s lending arm is generating more profit than ever. The Detroit News. https://www.detroitnews.com/story/business/autos/ford/2020/02/03/fords-lending-arm-generating-profit-ever/41133523/

[3] Colin Barr. (2009, June 22). Closing the industrial bank loophole may face challenges. CNN Money. https://money.cnn.com/2009/06/22/news/banks.loopholes.fortune/index.htm

[4] Adam Jonas & Evan Silverberg. (2022). Ford Motor Company: Ford’s EV Strategy Gets Raw: ICE Paying the Battery Bill [Research Update]. Morgan Stanley. https://research.etrade.net/eqr/article/webapp/09e69684-0925-11ed-a95a-800d82b59ab4?ch=rpint&sch=sr&sr=1

[5] Joseph White. (2022, August 22). Ford cuts 3,000 jobs as it pivots to EVs, software. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/business/autos-transportation/ford-cuts-3000-jobs-it-pivots-software-future-2022-08-22/

[6] Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. (2004). The FDIC’s Supervision of Industrial Loan Companies: A Historical Perspective. Supervisory Insights. https://www.fdic.gov/regulations/examinations/supervisory/insights/sisum04/sisummer04-article1.pdf

[7] Arthur Wilmarth. (2017, August 2). Beware the return of the ILC. American Banker. https://www.americanbanker.com/opinion/beware-the-return-of-the-ilc

[8] US Bureau of Economic Analysis. (n.d.). Total Vehicle Sales. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Retrieved August 16, 2022, from https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/TOTALSA

[9] Tim Sifert. (2022, February 18). Corporate Issuer: Ford Motor Electric Year. Refinitiv International Financing Review. https://www.ifre.com:443/story/3197104/corporate-issuer-ford-motor-1jx1sm7kbt

[10] Ford Credit. (2022, July 27). Q2 2022 Earnings Review. https://s23.q4cdn.com/799033206/files/doc_financials/2022/q2/Q2-2022-Ford-Credit-Earnings-Final.pdf

[11] Ford Motor Credit LLC. (n.d.). Ford Motor Credit LLC $10,000,000,000 Ford Interest Advantage Floating Rate Demand Notes Prospectus. Ford Investor Center. https://www.ford.com/finance/content/dam/ford64/us/pdf/investor-center/ford-interest-advantage-details/Ford_Motor_Credit_FIA_Prospectus.pdf

[12] Ford Motor Credit Company LLC. (2022). Annual Report for the Year Ended 2021 (No. 10-k). Securities and Exchange Commission. https://d18rn0p25nwr6d.cloudfront.net/CIK-0000038009/eaa057fc-e459-4692-9924-1a806103a15a.pdf

[13] Ford Motor Credit Company LLC. (2022). Annual Report for the Year Ended 2021 (No. 10-k). Securities and Exchange Commission. https://d18rn0p25nwr6d.cloudfront.net/CIK-0000038009/eaa057fc-e459-4692-9924-1a806103a15a.pdf

[14] Patrick Manzi. (2022, January 11). NADA Issues Analysis of 2021 Auto Sales, 2022 Sales Forecast. National Automobile Dealers Association. https://www.nada.org/nada/nada-headlines/nada-issues-analysis-2021-auto-sales-2022-sales-forecast

[15] Zippia. (2021, December 14). Hendrick Automotive Group Revenue—Zippia. https://www.zippia.com/hendrick-automotive-group-careers-26053/revenue/

[16] Ford Motor Credit Company LLC. (2022). Annual Report for the Year Ended 2021 (No. 10-k). Securities and Exchange Commission. https://d18rn0p25nwr6d.cloudfront.net/CIK-0000038009/eaa057fc-e459-4692-9924-1a806103a15a.pdf

[17] Ford Credit. September 21, 2022. Ford Credit Auto Lease Trust 2021-B Prospectus. Ford Motor Credit Company LLC. https://www.ford.com/finance/content/dam/abs-reports-pdf/ford/us/public-lease-securitization/ford-credit-auto-lease-trusts/prospectuses/FCALT%202021-B%20Prospectus.pdf

[18] Fifth Third Investor Relations. (2022). Fifth Third Corporate Highlights 2021. https://s23.q4cdn.com/252949160/files/doc_financials/2021/q4/FITB-4Q21-Fact-Sheet.pdf

[19] Comerica Bank Investor Relations. (2022, January 19). Comerica Earnings Release. https://investor.comerica.com/presentations-events

[20] Flagstar Bank. (n.d.). Annual Report for the Year Ending December 31, 2021 (Annual Report No. 10-K). https://d18rn0p25nwr6d.cloudfront.net/CIK-0001033012/6f65f17e-81c2-4841-a597-63235fcb9621.html

[21] Federal Reserve Board of Governors. (n.d.). Community Development Test for Wholesale and Limited Purpose Designations. Community Reinvestment Act. Retrieved August 16, 2022, from https://www.federalreserve.gov/consumerscommunities/cra_wholesale.htm

[22] Ford Credit Investor Relations. (2022). Q4 and Full Year 2021 Earnings Review. Ford Motor Company. https://s23.q4cdn.com/799033206/files/doc_financials/2021/q4/2021-Q4-Earnings-Ford-Credit.pdf

[23] Ford Credit. (n.d.). Ford® Privacy Policy | Ford.com. Ford Motor Company. Retrieved August 17, 2022, from https://www.ford.com/help/privacy/

[24] Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. (2004). The FDIC’s Supervision of Industrial Loan Companies: A Historical Perspective. Supervisory Insights. https://www.fdic.gov/regulations/examinations/supervisory/insights/sisum04/sisummer04-article1.pdf

[25] Keegan, J., & Ng, A. (2022, July 27). Who Is Collecting Data from Your Car? The Markup. https://themarkup.org/the-breakdown/2022/07/27/who-is-collecting-data-from-your-car