In communities of all sizes across the U.S. and Canada, affordable housing is a persistent challenge. In New Jersey, for example, as housing prices rise and wages remain low, many New Jerseyans are struggling to find and keep affordable housing. Fifty-two percent of New Jersey renters are “housing burdened,” meaning they spend more than 30% of their income on rent—and 33% of owners face the same problem. Housing is becoming less and less affordable and long-time residents are facing displacement, and gaps in homeownership continue to be a reflection of deep, systemic inequality across our neighborhoods.

Elected officials know that the feedback they receive on housing development and other project proposals often don’t match the full diversity of their constituencies. Recent research confirms this—the majority of individuals who share comments at zoning and planning meetings are older, male and homeowners. This leaves out a huge swath of community members—particularly women, people of color, recent immigrants and renters. It also means that feedback on major public projects—like building new affordable housing—often doesn’t reflect the opinions of those who would benefit most from them.

Participatory budgeting (PB) is a democratic process in which community members decide together how to spend part of a public budget. PB is a structured and proven way to combat these shortcomings because unlike traditional hearings or engagement strategies, involving community members through PB means their input can shape projects from the beginning—rather than at the end of a process, where feedback is less effective. By making sure those impacted most by the issues faced by your community have their say, PB can make policy-making more effective and equitable.

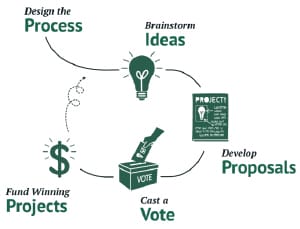

PB adapts to the needs of the community in which it is used, so while no two processes are the same, the overall process is comprised of 5 main elements:

- Design the Process: A steering committee that represents the community creates the rules and engagement plan.

- Brainstorm Ideas: Through meetings and online tools, residents share and discuss ideas for projects.

- Develop Proposals: Volunteer “budget delegates” develop the ideas into feasible proposals.

- Cast a Vote: Residents vote on the proposals that most serve the community’s needs. When a process is designed equitably, residents of all ages, backgrounds, citizenship statuses, etc. can be eligible to participate.

- Fund Winning Projects: The government or institution funds and implements the winning ideas.

PB is a growing practice across the U.S. and Canada. While it originated in Porto Alegre, Brazil, PB has been adopted by over 3,000 cities around the world where processes have resulted in more inclusive political participation, especially by historically marginalized communities and more equitable and effective public spending.

PB is a growing practice across the U.S. and Canada. While it originated in Porto Alegre, Brazil, PB has been adopted by over 3,000 cities around the world where processes have resulted in more inclusive political participation, especially by historically marginalized communities and more equitable and effective public spending.

In the United States, PB has been used as a tool for letting community members propose and prioritize the projects that can help keep or make their neighborhoods affordable and housing accessible. In Oakland, California, residents used Community Development Block Grant funds administered by the US Department of Housing and Urban Development

to invest in programs that provide fair housing counseling and legal advice to tenants at risk of eviction and predatory rent increases. Residents also prioritized programs that provide meals, sanitation kits, access to showers and health related services to homeless individuals and encampments using mobile services and complimentary programming.

In Rochester, New York, the Rochester-Monroe Anti Poverty Initiative used Community Services Block Grants to run a PB process where community members invested in developing a prototype for a tiny house project that would provide very low-income individuals, particularly veterans, with affordable permanent housing. Residents also invested in a housing fund to provide rapid response for community members facing homelessness, keeping people housed and improving coordination of resources for those in need of support.

Funding for PB and Additional Resources

A frequent question from government and community leaders is, “Where do we find the money to allocate via participatory budgeting?”

It is important to emphasize that communities do not need “extra” or discretionary funds to implement PB. Even in communities under the tightest of fiscal situations, many existing funding streams are subject to some degree of decision-making discretion — typically exercised by elected officials, agency heads and/or appointed commissions. Municipal charters and grant streams also typically have requirements for public engagement before major funding decisions are final. PB is an engagement strategy that identifies where shared decision-making can occur in planned budget decisions while also leading to more effective spending, broader political participation, support for new community leaders and stronger relationships between formal decision-makers and those impacted by these decisions.

Based on interviews and research conducted by the Participatory Budgeting Project in New Jersey, we now have new resources that outline funding that can be used for PB in the United States to specifically address affordable housing needs, funding that has not been used for PB before but has promise in expanding affordable housing and case studies that share more about how this has worked in practice.

Download our new guide to Participatory Budgeting for Affordable Housing and visit PBcan.org to learn more about how PB can address affordable housing and other related opportunities including transportation and climate resilience.

Participatory Budgeting is a key element of greater equity in our communities and creating a #JustEconomy.

Based in Oakland, CA, Kristania De Leon manages PBP’s network building and advocacy to increase the demand, visibility and impact of PB efforts across the U.S. and Canada. She brings over a decade of non-profit experience having worked with domestic and international teams committed to improving human rights, social determinants of health, and equity.

Photo by Tim Mossholder on Unsplash