— Key Takeaways

- Even after troubling findings from previous mystery shopper tests were published and in the news, financial institutions continued to create barriers for minorities and women business owners to access PPP loans.

- In a new round of tests at 47 different financial institutions in the Los Angeles region, Black female and Hispanic male testers were treated less favorably than White testers even though the minority testers had stronger financial profiles.

- The testing revealed the behaviors that financial institutions implement to discourage members of protected classes from applying for credit.

- The government should get serious about collecting lending data to detect demographic patterns and discrepancies; lenders should get serious about anti-discrimination training for their employees; and those that discriminate should face more serious consequences from regulators.

— Key FINDINGS

- Black female and Hispanic male testers received significantly less information about PPP loan products than their White male counterparts.

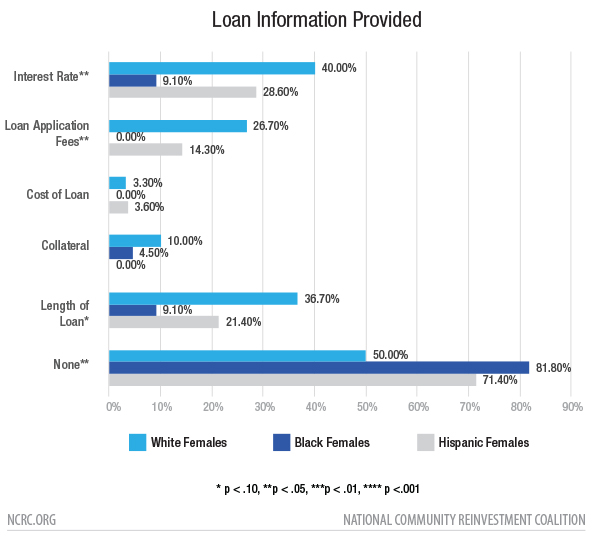

- Black female testers were provided less information about loan products and discouraged more compared to White female and Hispanic female testers.

- Under the fair lending review, we observed a difference in treatment of Hispanic females and Black females through overt statements, information asymmetry and discouragement to continue pursuing a banking relationship.

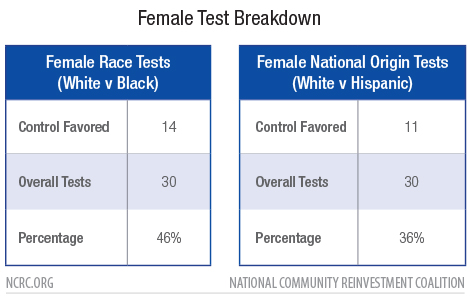

- Female multi-layered tests:

- 16 out of 30 (53%) tests revealed a difference in treatment based on race and/or national origin

- 46% of the Black female testers received worse treatment

- 36% of Hispanic female testers received worse treatment

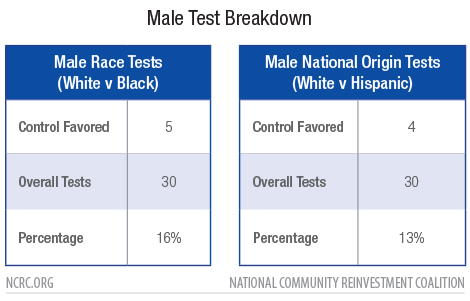

- Male multi-layered tests:

- 5 out of 30 (16%) tests revealed a difference in treatment based on race and/or national origin

- 16% of the Black male testers received worse treatment

- 13% of Hispanic male testers received worse treatment

Anneliese Lederer, Director of Fair Lending and Consumer Protections

Sara Oros, Program Coordinator, Fair Lending and Fair Housing

In collaboration with:

Dr. Sterling Bone, Professor of Marketing, Utah State University

Dr. Glenn Christensen, Associate Professor of Marketing, Brigham Young University

Dr. Jerome Williams, Distinguished Professor and Prudential Chair in Business, Rutgers University

Executive Summary

NCRC, in collaboration with our academic partners, conducted 60 pre-application mystery shopper tests by telephone with 47 different financial institutions in the Los Angeles, California, metropolitan statistical area (MSA) from July 27 to August 7, 2020, during the last two weeks that federal Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) loans were available to businesses impacted by the coronavirus pandemic. This study was to determine if financial institutions changed their behaviors after being made aware of our previous testing conducted in the Washington, D.C., MSA. The results of that testing were widely reported by the media, including The New York Times, Politico, The Hill and ABC News. The follow-up tests in Los Angeles revealed a combined 21 out of 60 (35%) tests where the White tester was favored over either or both of the Black and Hispanic Testers in violation of the Equal Credit Opportunity Act (ECOA) of 1974. For this round of testing, we conducted 60 multi-layered matched tests which consisted of a Hispanic, Black and White tester each contacting the same financial institution to request information. Thirty of these multi-layered matched tests were conducted by female testers and thirty by male testers. We tested 60 branches from 47 different financial institutions including some national institutions that we had tested in Washington, D.C., during the first round.

We conducted two types of analysis to determine the level and manner of discrimination. The first data analysis approach employs statistical testing using the chi-squaredifference test to compare tester survey responses across the protected and control groups. This approach examines behaviors across the marketplace as a whole. To understand differences at the bank and branch level, we employ a second approach of a fair lending review. With this approach, fair lending experts review the different tests by the bank branch to determine differences in treatment.

The testing revealed a combined 21 out of 60 (35%) tests where the White tester was favored over either or both of the Black and Hispanic Testers in violation of ECOA. More specifically, we observed:

Female multi-layered tests:

- 16 out of 30 (53%) tests revealed a difference in treatment based on race and/or national origin

- 46% of the Black female testers received worse treatment

- 36% of Hispanic female testers received worse treatment

Male multi-layered tests:

- 5 out of 30 (16%) tests revealed a difference in treatment based on race and/or national origin

- 16% of the Black male testers received worse treatment

- 13% of Hispanic male testers received worse treatment

To combat these discriminatory behaviors, lenders should conduct additional training of staff and perform their own mystery shopping. Policymakers should allocate specific percentages of the remaining PPP funding to be originated by community banks, CDFIs and minority depository institutions, provide additional, ongoing support for small businesses facing continued hardship, and ensure that small businesses that received PPP loans are not saddled with long-term debt by automatically forgiving PPP loans under $150,000.

Introduction

In a perfect free market economy, everyone is openly provided with all the information needed to make an educated decision. However, we do not live in a perfect free market society because discrimination occurs and is often manifested through information asymmetry. In particular, information asymmetry occurs in lending when one tester receives more or better information from a financial institution than other testers. With this advantage, the tester with more robust information has more choices and opportunities to consider.[2] Matched-pair testing uncovers this asymmetry and reveals the barriers that women and minorities face in accessing capital. Historically, it has been difficult for women to obtain credit, resulting in the creation of fair lending laws and specifically, the Equal Credit Opportunity Act (ECOA) of 1974, which gave women the ability to obtain a credit card without the permission of their fathers or husbands. The ECOA applies to all forms of lending and makes it illegal to discriminate on the basis of a protected class.[3]

Women-owned businesses are vital to a strong economy. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, women-owned businesses employed 14% of the workforce, supporting over 16 million people. Between 2014-2019, the number of overall women-owned businesses grew at a rate of 21% compared to 9% of the overall private sector. The number of minority-owned women businesses grew even more, at 43%. About half of women-owned businesses are concentrated in three industries; Healthcare and Social Assistance, Professional/Scientific/Technical Services and Other Services. In 2019, a report commissioned by American Express stated that women of color operated 50% of all women-owned businesses and generated $422.5 billion in revenue.

Unfortunately, the impact of COVID-19 has hit small businesses especially hard. In response, Congress created the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) designed to provide a grant-like incentive for small businesses to keep their employees on payroll, and provide support for business mortgages, rent and utilities during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, if a small business does not use at least 60% of the funds to keep people on payroll and avoid layoffs, then the funding becomes a loan. This was a widely reported and promoted program by the current administration; however, with the closing of new applicants on August 8th, 2020, $133,987,798,876 of the slated funding remains untouched.

At its closing, 5,212,128 loans had been made by 5,460 lenders for a total of $525,012,201,124 in money distributed. The average loan size was $101,000. Borrower business name and street address data have still not been released by the U.S. Treasury Department or Small Business Administration for loans less than $150,000, which is 87.4% of the loans that were made. Furthermore, demographic information such as race, ethnicity and gender of the borrowers was not usually collected at the time of application. At the close of PPP funding, Health Care and Social Assistance and Professional/Scientific/Technical Services were the top two industries that received funding.

The state of California approved 623,360 loans that totaled $68,644,418,670, which is more than any other state or territory. NCRC tested in the Los Angeles MSA area during the final two weeks of PPP lending activity from July 27-August 7, 2020.

PPP Lending To Women And Minority-Owned Businesses

While accessing PPP funding during the first round of the program was challenging for all businesses, there is evidence that businesses owned by people of color and located in communities of color were less likely than White businesses to access PPP funds.

Small Business Majority, a network of small businesses focused on the promotion of equitable small business growth, conducted a survey from 374 businesses in their network between May 22 and May 27, 2020. Results from this survey revealed that of all respondents who did not apply for PPP, 19% said they were either told they would not qualify or believed they would not, and 12% could not find a bank to apply for a PPP loan. This supports frequent concerns that many banks prioritized servicing current clients during the first round of PPP funding.

Further research suggests that small business owners of color and businesses in communities of color faced challenges applying for and being approved for PPP funding. More detailed, loan-level analysis is difficult; however, due to frequent missing data on the race and ethnicity, gender and veteran status of the borrower available in the PPP data released to date. SBA program loan forms give borrowers the option to disclose race, ethnicity, gender and veteran status, although this disclosure is voluntary. However, in the collection of PPP data, the SBA excluded optional standard demographic variables in the initial application forms. While these variables were eventually included, the delay and optional disclosure requirements mean that only 23% of the loan records included race or gender data.

The SBA Inspector General released a report admitting that the SBA did not provide any guidance to lenders at the beginning of PPP lending to prioritize borrowers in underserved and rural markets. The House Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus crisis found that “…the Trump Administration and big banks failed to prioritize small businesses in underserved Markets, including minority and women-owned businesses.” This resulted in “longer waits” and “more obstacles to receiving PPP funding than larger, wealthier companies.” In addition, due to the lack of demographic data collected, there is no way for the SBA to adequately determine the loans that were distributed to those markets.

The public health crisis has already begun to show signs of disproportionately affecting women, and data proves that women are more vulnerable to discrimination in lending. Despite the lack of PPP borrower data, our mystery shopping during this time provides data on the availability of credit to different consumers. Our tests continue to reveal patterns of discouragement for minority and women-owned businesses. This paper focuses on the mechanisms of discouragement using both a statistical and fair lending analysis. Both analysis methods reveal that the minority female testers experienced a significant difference in treatment compared to White female testers when requesting information about loan products. In the fair lending analysis, the female testers also experienced this barrier of discouragement at a higher frequency than the male testers. Understanding the mechanisms of discouragement is vital to breaking down the barriers to accessing credit, as discouragement results in business owners not applying for credit when they should. Without equal access to safe credit products, our economy will not rebound from the devastating effects of this pandemic. COVID-19 is going to severely impact the growth and development momentum that women-owned businesses have had in recent years.

Testing Methodology

NCRC, in collaboration with our academic partners, conducted pre-application multi-layered matched testing for race and national origin in the Los Angeles MSA.[4] Multi-layered matched testing consists of a control and members of two different protected classes, contacting a bank branch to determine if there is a difference in treatment. The multi-layered matched testing only occurs in the pre-application phase with the tester requesting information about loan products. For this round of testing, we conducted 30 male and 30 female multi-layered matched tests consisting of White, Black and Hispanic testers. We had a total of 180 interactions with the bank branches.

In these tests, we contacted 60 bank branches representing 47 different financial institutions. The financial institutions were randomly selected from all small business lending institutions, both national and regional banks, and comprise over 50% of the institutions operating in the market. The sample of banks in the Los Angeles market were randomly selected to represent a broad cross-section of the small business lending marketplace. The banks selected ranged from lenders with assets over $10 billion to community banks. The purpose of the research is to determine the baseline customer service level that male and female testers of different racial and national origin backgrounds receive when seeking information about small business loans to help keep their businesses open during the COVID-19 crisis. NCRC started testing on July 27, 2020, and completed the testing on August 7, 2020, the day before PPP lending ended.

Testing is a critical tool for fair lending enforcement used to assess equal access to credit. Federal agencies also conduct similar testing to investigate when they have been alerted to suspicious behavior. Matched pair testing, such as this, is the only method to measure pre-application discrimination and discouragement since banks do not collect data on loan inquires prior to an application being submitted. The Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) partners with fair housing groups to do testing under their Fair Housing Initiatives Program (FHIP). The Department of Justice (DOJ) Civil Rights Division has taken on many cases developed from its testing program. Additionally, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) has taken enforcement action against Bancorpsouth after implementing testing that revealed multiple threats to consumers’ fair and equal access to mortgages. The U.S. Supreme Court has upheld testing as a crucial private enforcement tool in fighting against civil rights violations.

NCRC and our academic partners conducted these tests as phone inquiries since many bank branches remain closed to in-person services due to the pandemic. Tester profiles were controlled with racially identifiable names and each tester was required to pass a voice panel test to determine whether or not their perceived race could be determined over the phone. Testers were only used if their voice was perceived to be racially identifiable by a blind panel. Research shows that the race of an individual can often be determined by their names alone. We selected profile names after researching names most often perceived with a particular race, and like testers’ voices, we presented those names to a national survey panel to identify names perceived to be highly correlated with gender (male and female) and race/national origin (Black, Hispanic, White). Research also reveals that linguistic profiling occurs over the phone, and that many Americans are able to accurately guess social demographics such as race over the phone after a few sentences.

As with our previous work, this study was designed to answer the following research questions: Are minority and non-minority small business owners with similar economic and business profiles:

- Presented with the same information?

- Required to provide the same information?

- Given the same level of service quality and encouragement?

The matched-pair mystery shoppers had nearly identical business profiles and strong credit histories to inquire about small business products to maintain their business during the COVID-19 pandemic. The profiles of all testers were sufficiently strong that, on paper, they would all qualify for a loan. Furthermore, the protected Black and Hispanic tester profiles were intentionally designed to be slightly better than their White counterparts in terms of income, assets and credit scores. This was done to make it a more conservative test of any differential treatment. Immediately following the interaction, testers were asked to answer either yes or no about whether specific behaviors, queries and comments were made by bank employees. They were also required to provide a narrative of the interaction.

Analysis of the data was done under two different reviews: chi-square statistical difference tests and a fair lending review. For the chi-square difference, we applied statistical analysis in evaluating whether differences in the interactions between White testers, Black testers and Hispanic testers, were significant across all of the banks visited. The chi-square test for independence, is a particularly robust way for social scientists to evaluate whether or not there are substantial differences in outcomes between groups. Testers were asked simple “yes or no” questions in a survey about their interaction with bank personnel and the number of interactions observed ensures a high level of validity. To make certain we were analyzing and comparing cases that reached a similar point-of-contact with the bank, we only included in these analyses those cases where the tester was able to speak to a bank representative regarding their small business loan request. In total, there were 22 White male, 27 Black male, 27 Hispanic male, 30 White female, 22 Black female and 28 Hispanic female tests that met those requirements and were analyzed using Chi-square difference tests.

For the fair lending review, each of the narratives were analyzed independently by two fair lending experts as a matched-pair set (White to Black and White to Hispanic) to determine a difference in treatment under fair lending standards. We used four categories to determine a difference in treatment: lack of encouragement, difference in products, difference in information provided and difference in information requested. For each case where one of these differences was identified, we added a tally to report a total number of discrimination counts. The testing once again revealed major differences in treatment.

Any differences in treatment between White and Hispanic/Black testers are particularly troubling because the combined effect of these various differential treatments may lead to feelings of discouragement and despondency among minority entrepreneurs in the financial marketplace. There is some evidence that this may already be happening. The Federal Reserve Small Business Credit Survey 2019 Report on Nonemployer Firms states that 13% of all small business owners do not apply for credit because they are discouraged. However, in the same report, the rate of discouragement among minority entrepreneurs is markedly higher at 27% for Black entrepreneurs and 21% for Hispanic entrepreneurs.

For our fair lending review, we looked to the Equal Credit Opportunity Act (ECOA), the fair lending law that applies to small business loans. ECOA makes it illegal for a member of a protected class to be discriminated against in any aspect of a credit transaction, which includes the pre-application arena. Protected classes under ECOA include: race, color, religion, national origin, sex, marital status or age (provided the applicant has the capacity to contract); to the fact that all or part of the applicant’s income derives from a public assistance program; or to the fact that the applicant has in good faith exercised any right under the Consumer Credit Protection Act. Discrimination occurs when a protected applicant is offered different products, provided different information or experienced discouragement to apply or pursue a loan compared to the non-protected applicant.

Discrimination can be found through either overt statements, disparate impact or disparate treatment. Disparate impact is a neutral policy that has an adverse disproportionate effect against a protected class. This can be shown through the use of statistical tools. Disparate treatment compares the treatment between two individuals with one of the individuals being a member of a protected class. Disparate treatment can range from subtle differences in treatment to more overt cases. The chi-square analysis revealed statistical significance and supported the analysis that disparate impact was seen across the marketplace, which will require large-scale reform. The fair lending analysis of the individual matched-pair tests revealed disparate treatment between classes, which can be addressed individually through cases filed under ECOA.

Results

Overall, the analysis revealed statistically significant differences in how the male and female testers were treated throughout the interaction. Our chi-square analysis revealed that the Black female testers, across the marketplace as a whole, were treated significantly worse compared to the Hispanic and White female testers. While the difference in treatment for male testers only rose to significance in a few areas.[5]

In addition to the statistical tests, the fair lending analysis of all the individual male and female matched-pair multi-layered tests found that a combined 21 out of 60 (35%) tests revealed a difference in treatment with the White tester being favored over either or both of the Black and Hispanic testers in violation of ECOA. There were 57 different instances of discrimination in this round that the Black and Hispanic testers experienced.

More specifically, in the fair lending analysis of the female multi-layered matched tests, we found that 16 out of 30 (53%) tests revealed a difference in treatment based on race and/or national origin. When we look at the specific tests by protected class, we found that the Black females received worse treatment in 46% of the female tests and the Hispanic females received worse treatment in 36% of the female tests. Combined, there were 44 different instances of discrimination that the Hispanic and Black female testers experienced.

In the fair lending analysis of individual matched-pair tests for male testers, we found that five out of 30 (16%) tests revealed a difference in treatment based on race and/or national origin. Black males received worse treatment in 16% of the male tests. Hispanic males received worse treatment in 13% of the male tests.

Of the 47 different financial institutions tested in this audit, 19 (40%) institutions had at least one test that showed the control tester was favored.

While we identified concerning behavior among the male-controlled tests, our statistical tests and fair lending review found that the female testers were more likely to be discouraged in this round of testing. We found that the Black and Hispanic female testers received worse treatment through overt statements, information asymmetry and discouragement. We found that these different types of discouragement occurred for women throughout the interaction with the loan officer. Male testers experienced this type of discouragement as well, but at a lower frequency rate. Therefore, the majority of the remainder of this paper will focus on female tester experience.

Overt statements

An overt statement of discouragement in the pre-application process occurs when the applicant who is a member of a protected class is bluntly told while information gathering only, that they will not qualify for a loan or should not apply for a loan at this financial institution or at other financial institutions. The fair lending review reveals these types of statements.

- At one financial institution, the Black Female tester was told “that my business was not the type of business they would do loans for and he stated that [X type of business] was not a stable business to be in. He spoke in a negative manner about my business saying that I would probably have some difficulty getting a loan.”

The bank officer’s statement is overt as he is outright discouraging her from not only applying for a loan at their bank but also discouraging her from inquiring about a loan at another institution by telling her that she will probably have difficulty getting a loan. The Black tester’s financial profile was stronger than the White tester, who had a business in the same industry and was informed about a business loan and given information about the application process and interest rates.

- At another financial institution, the Black Female tester was asked questions about business income and told “that if my business was not doing well, at this time I would not qualify for any type of loan.” The White tester in contrast, was never asked for her business income; instead she was recommended a line of credit and given information about interest rates and fees.

This statement is overt as the bank officer is discouraging the Black tester from applying as he has informed her that she will not qualify for a loan because she has been impacted by the pandemic. The Black tester’s financial profile was better than the White tester’s profile; furthermore, the purpose of this testing is to inquire about products due to the negative economic effects of the pandemic.

Information Asymmetry

The purpose for the interaction between business owner and bank employee is the collection of information. The more information a business owner receives from the bank employee the more complete their decision making can be. Information is not limited to the number of products being offered but also to the details about these products like interest rates, fees and collateral requirements.

The offering of different products to applicants who have financially similar profiles is an ECOA violation. During the testing period, one of the lending products available was a PPP loan. The testing revealed a statistically significant difference across the banks tested with the Black female testers and Hispanic male testers provided less information about PPP loans than their White and Black counterparts. There was no significant difference between the White and Black male testers or White and Hispanic female testers in this area.

We also tested the consistency of information surrounding basic elements of a loan — the interest rate offered, loan application fees, cost of the loan, need for collateral and loan length — being provided by bank employees. There was also a “None” variable for no information provided. We found that across the marketplace a statistically significant portion of Black female testers are either not provided with any information about loan products and their features, or the information provided is limited. Asymmetric information gathering impacts the Black tester’s ability to make an educated decision compared to both the White female and the Hispanic female testers. A decision made with partial information disadvantages the borrower to such a degree that it may potentially harm the business.

Under a fair lending review at one financial institution, all three female testers spoke to the same loan officer within three days of each other about products to help their business. Each tester was told about a few products but then the loan officer steered each tester in a different direction regarding recommendations.

- The Hispanic tester was told their best option would be to contact their current bank and seek out a PPP loan.

- The Black tester was told they could receive a line of credit and was provided information about interest rates and approval times.

- The White tester was told about an Economic Injury Disaster Loan (EIDL) and how it would be “quick to get, and did not use as much scrutiny as ordinary loans.”

The offering of different products to similarly situated potential applicants is a violation of ECOA as these testers all had similar financial profiles and should have been recommended the same products, as well as provided with similar information to make a decision.

Steering to HELOC

A major problem within information asymmetry is steering an applicant to a specific product. This suggests that the loan officer is able to make the judgement for the applicant about what is best for them without giving the applicant the choice to make their own decision. Steering is a violation of ECOA. In this round of testing, five testers were offered non-business loan products, specifically a Home Equity Line of Credit (HELOC).

The fair lending review revealed that two White male testers, one Black female tester, one White female tester, and one Black male tester were offered HELOCs.

- A White male tester was told he could borrow the full amount requested by applying for a HELOC compared to applying for a regular business line of credit which would qualify for a smaller amount. The Hispanic tester was told simply they would not qualify for the full amount requested and encouraged to try a different bank.[6]

- In three different tests, the White female, Black female and Black male testers were informed that a HELOC was the only product available.

Discouragement

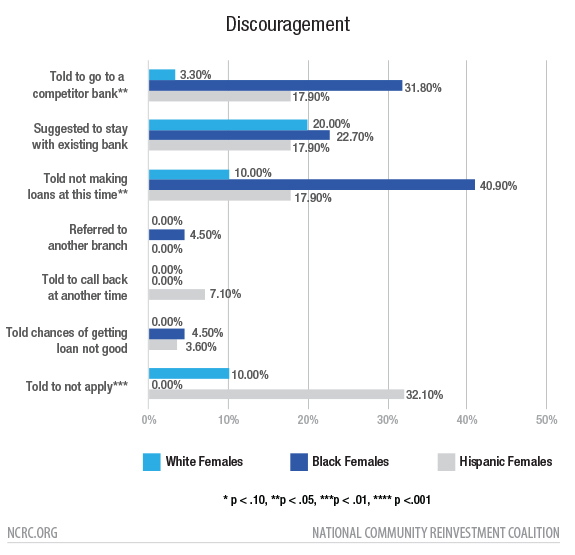

In our first PPP paper that focused on the Washington, D.C., marketplace, the fair lending review revealed that White testers were encouraged to apply for loans with thefinancial institution more often than Black testers. Encouragement to apply for a loan was revealed through statements made to different testers. In this round of testing in Los Angeles, we focused on determining if specific discouragement statements rose to the level of statistical significance. We added additional measures in the tester survey to determine if testers were being discouraged at equal levels from applying.

The collection of this new data, reveals that there are a number of mechanisms bank employees implement to discourage the Black and Hispanic female testers. Specifically, Black female testers were told to go to a competitor bank or that they were not making loans at this time. The Hispanic female testers were told not to apply. In both cases, there were statistically significant differences in treatment.

In addition to the statistical tests, the fair lending review revealed discouragement of the Black and Hispanic testers in the following ways.

- The White tester was given information about a business loan while the Black tester was “informed [that] their bank is not offering any type of business loans” and the loan officer suggested the tester go through a larger bank such as Chase, Wells Fargo or Bank of America.

This statement to the Black tester is a violation of ECOA because the tester is being discouraged from pursuing a loan at the tested financial institution as she is told that no lending is currently occurring which is not true as the White tester was told about loan products. Again, the financial profile of the Black tester was stronger than the White tester and she should not have been discouraged from pursuing a loan at the tested institution.

- The White female tester was encouraged to apply in the interaction while both the Black and Hispanic female testers were discouraged from applying at that bank. Specifically, the:

- White tester was able to receive information from the loan officer over the phone about a term loan including interest rates, approval times and fees.

- Hispanic tester was told “to go there to do a walk in or she could also give me the SBA department phone number.” She was also told that “due to COVID-19 they are currently not doing small business loans right now.”

- Black tester was told to go to the website for information. “She then began explaining that even though the bank has a business loan department, they too would recommend I go to the bank website for this is the only way to apply.”

Double Impact: Discouragement and Different Products Offered

In our fair lending analysis, we observed a double impact in 13 out of 21 (62%) multi-layered matched tests where the White tester was favored. This double impact, discussed in our previous PPP report, occurs when the bank employee discourages the Black or Hispanic tester from becoming a customer of the bank while providing a similarly situated White tester with information about different loan products, and often also encouraging them to become a customer. The double impact is revealed when the totality of the test is analyzed under the fair lending review. We observe the double impact in the following manner:

- In one test, both the Hispanic and Black testers were discouraged from applying for products at the bank while the White tester was given detailed information about two different products. Specifically, the Hispanic tester was told they could not disclose product information over the phone, but the White tester had no barriers in receiving the information.

- The Hispanic tester was advised by the loan officer “to come into the branch because she was not able to provide me with the basic information I was requesting.” The tester pushed back over concerns with COVID-19 and was told that the loan officer “would prefer to go over those things in person.”

- The Black tester was told that the bank was “no longer doing the PPP loan but the SBA loan. Then she said someone will call me back.” But the tester never received any follow up.

- The White tester was told information about a line of credit and a flexible loan product including interest rates, monthly payments and approval times for each. At one point in the interaction the loan officer said they would need to look up additional information and return the call, and the tester received that follow up a few hours after and continued to get information on products.

- In another test, the Black and Hispanic testers were told they would not be able to receive regular business products from the bank and that they should go to their current bank for help. In contrast, the White tester was given information about traditional loan products and received two follow up emails from loan officers.

- The Hispanic tester was told “that it would be smarter to pursue a loan from the bank that I currently have a relationship with…He said they are currently only working with people that are existing clients.”

- The Black tester was recommended to try their current bank “because they [the tested bank] do not do loans that size.”

- The White tester was told “they were not doing PPP loans at the moment, but they were doing traditional loans.” The tester was told they would not likely be able to receive the full amount requested but could qualify for a smaller amount. Tester received two follow up emails from the bank afterwards requesting more information to start an application.

- In one test, both the Hispanic and Black testers were discouraged from applying for products at the bank while the White tester was given detailed information about two different products. Specifically, the Hispanic tester was told they could not disclose product information over the phone, but the White tester had no barriers in receiving the information.

In the Los Angeles testing, we observed a pattern of double impact in 13 out of 21 (62%) multi-layered matched tests where the White tester was favored, which is 21% of all tests. The female testers experienced this double impact more often than the male testers in Los Angeles, whereas in Washington, D.C., this behavior occurred more often to the male testers. In DC, we observed 12 out of 27 tests where differential treatment was identified which is 19% of all tests and 44% of differential treatment tests. The finding of the double impact effect in two large metropolitan areas highlights that this is potentially a widespread practice and fair lending violations are occurring more frequently.

NCRC Recommendations

The results of this testing demonstrate that women, and in particular, women of color faced challenges accessing PPP funding during a critical time in this crisis. Delays and discouragement in applying for critical revenue replacement funds have profound ramifications for the sustainability of those businesses, and their ability to remain open or reopen. Delays and discouragement could mean the difference between participating in an economic recovery or not reopening at all.

Improving data disclosure, strengthening the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) and addressing barriers to access to PPP and future revenue replacement programs must be addressed, along with improving lender testing, compliance, hiring and training practices. As the current economic and public health crisis continues to unfold, NCRC also supports continued efforts to ensure the financial stability of existing small businesses and the availability of credit to new small businesses that will help drive the recovery.

Policymakers should take steps to increase access to capital for small businesses owned by women and people of color.

Collect and disclose small business application and approval data to help identify fair lending concerns

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) should finish the rulemaking process implementing new small business data disclosure requirements without delay. On September 15, 2020, the CFPB took an important first step in implementing section 1071 of the Dodd-Frank Act by publishing potential proposals for public review and comment as required by the Small Business Regulatory Enforcement Fairness Act (SBREFA). If applied to all lenders consistently and if all types of small business loans are captured, the data provided under Section 1071 will provide the market-wide view of loans made to small businesses and will provide unprecedented transparency into how and where small businesses loans are made to women and business owners of color.

Modernize CRA and ensure that banks and other lenders serve the credit needs of small businesses, including those owned by women and people of color

CRA provides a powerful incentive to ensure that banks provide small businesses with access to capital. NCRC research has found that weakening CRA could reduce small business lending in low- and moderate-income communities by $8 billion to $16 billion over five years, and many non-depository small business lenders are exempt from CRA requirements all together. Efforts to expand access to small business credit, particularly for very small businesses and businesses owned by women and people of color must be included in efforts to modernize CRA. Proposals that weaken CRA and decrease the obligation of lenders to serve the credit needs of small businesses should be opposed.

Ensure that existing and any future PPP or small business revenue replacement program supports small businesses owned by women and people of color and ensure that existing PPP loans are not converted into long-term debt

- Congress should allocate remaining PPP funding and additional funds to support small businesses, particularly businesses owned by people of color, woman-owned businesses and very small businesses that were unable to access funding in the first two rounds. Second loans should only be made available to those businesses that can demonstrate continued hardship, with priority given to underserved markets identified by the SBA Inspector General that were not prioritized during the first two rounds of PPP. Eligibility requirements should be amended further to ensure access for and justice to all involved business owners.

- Additional PPP funding or any new revenue replacement program should include set-aside for loans originated by Community Development Financial Institutions and Minority Depository Institutions that are well-positioned to serve the credit needs of small businesses owned by woman and people of color that were not well served by the initial rounds of PPP funding.

- Congress should act to streamline forgiveness for PPP loans less than $150,000. A streamlined, automatic forgiveness form would ensure that the forgiveness application process does not burden small businesses that may not have full-time accounting staff. This process would also ensure that borrowers would still have the opportunity to disclose important demographic data that was missing from the initial PPP application forms. Streamlined, automatic forgiveness would help ensure that an overly complicated forgiveness process does not result in these loans, intended as grants, being converted into long-term debt.

Increase Funding to Women Business Centers

- Congress should increase the yearly allocated funding for Women and Minority Business Centers. These institutions play a vital role in educating and guiding new business owners. They help to create healthy businesses that have the ability to create wealth for people and stabilize neighborhoods.

Enforcement Actions

The CFPB needs to initiate enforcement actions under ECOA. ECOA stipulates that the CFPB has the ability to conduct enforcement actions against financial institutions that are violating this act. Since its inception, the CFPB has not brought forth an ECOA case in the small business arena.

Lenders must take additional steps to prevent fair lending violations

Conduct Statistical Analyses of Denied or Not Fully Funded PPP Applications

Financial institutions should invest time into reviewing PPP applications they denied or did not fully fund to ensure there is no difference in treatment or disparate impact created by their decision making.

Strengthen Internal Compliance Programs

Financial institutions must strengthen their compliance programs to ensure that they follow ECOA and other fair lending laws. This compliance program must include matched-pair testing as it exposes weaknesses that need to be corrected through training.

Improve Hiring and Training Practices

Financial institutions need to train their employees better. Training is a valuable tool that provides employees with an understanding of protocol, expectations and laws. Additionally, they should seek to hire more diverse staff that represents the individuals in the community they are serving. Hiring a more diverse staff is essential, because it helps to limit biases.

PPP lenders should commit to increasing their annual support to small businesses affected by COVID-19 by at least the amount they received in PPP fees, compared to pre-pandemic levels.

Financial institutions that participated in the PPP program received billions in fees and, in many cases, expanded their customer base and established new relationships with small businesses. PPP lenders should commit to the continued support of small businesses approved for PPP loans through additional forgivable loans as available, grants and technical assistance to ensure they have the capital and expertise they need to participate in the recovery. At the same time, lenders should provide outreach to those small businesses that were denied loans during the application process and partner with direct services programs to help identify small businesses that may have been discouraged from applying at all.

Conclusion

Women-owned businesses are vital to the sustenance of a strong and growing economy. As the COVID-19 pandemic persists and the economy continues to suffer, our tests revealed that lending discrimination is still playing a role in minority and women-owned businesses not being able to access help from financial institutions to keep their businesses open. The differences in treatment observed in this round of testing confirm that there is still not enough being done to ensure that all equally qualified business owners have equal access to credit.

———

[1] We would like to acknowledge the help of Bruce Mitchell PHD, Alyssa McKenzie and Sean Ruddy.

[2]While information asymmetry is often defined differently in economic literature (Stiglitz and Weiss 1981)(Asiedu,Freeman, Nti-Addae 2012), we will be using the above definition for this paper.

[3] Protected classes under ECOA are: color, race, national origin, sex, marital status, religion, familial status, age, source of income, and retaliation under the Consumer Credit Protection Act.

[4] In 2018, NCRC conducted fair lending testing in the Los Angeles, MSA. Here is a link to the results from those multi-layered matched tests.

[5] See chart titled “Payroll Protection Plan (PPP) Information Provided”, we observed that Hispanic male testers received statistically significantly less information about PPP loans than White and Black male testers.

[6] The Black tester was not able to reach a loan officer in this test.