The government’s Paycheck Protection Program data is so flawed it is virtually useless to the public, consumer advocates or public officials who want to know who received money from the program, if there was any bias in how the money was distributed, or how much money went to specific communities. But the data gaps could be corrected if the government moves quickly to ensure more demographic information is gathered when small businesses apply to have their PPP loans forgiven.

Introduction

On July 6, 2020, the Small Business Administration (SBA), bowing to pressure from Congress, community groups and the public, released a more detailed view of loans made under the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) between April 3, 2020, and June 30, 2020. Under this program, businesses can apply for a loan which will be forgiven once they fulfill the requirements of the program.

The massive scale of the economic fallout brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic has created a profound anomaly, leaving millions unemployed and stagnating small business growth across the U.S. Main Street needed a bailout. Congress created the PPP to provide that help. However, the focus at the federal level did not initially consider transparency. This mistake has damaged public trust in both the program and the SBA.

The decision to release PPP data followed weeks of Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin steadfastly refusing to disclose what he felt was “proprietary” information. White House economic adviser Larry Kudlow went even further, noting that the administration “never promised” to release detailed information about the loan recipients. Neither Mnuchin nor Kudlow seemed aware that the SBA advises loan recipients that their information would be released and that the agency has released detailed loan level data about their borrowers for years for the public to analyze.

The reaction to the new PPP data released earlier this month has not been very positive. With over $100 billion dollars still available, business owners complain that they are still waiting for their applications to be processed and many complain that they were denied loans they needed to sustain their business. Some businesses have complained that they are listed in the data despite never having applied for a PPP loan. The term “PPP shaming,” referring to when businesses are deemed unworthy of receiving the program’s grants, has entered the lexicon. Despite reports that suggest some borrowers might have had alternatives to a PPP loan, the data simply doesn’t allow us the ability to determine much about who got the loans or what the loans paid for.

After reviewing the data, NCRC has found significant flaws that preclude a useful analysis. Here we discuss these problems and offer solutions that might help the SBA make PPP data more effective for the public, business owners,consumer advocates and policy makers.

The data was divided into two files based on the dollar amount of the loan. One included 661,218 loans for $150,000 or more and the other had 4,219,761 loans for less than $150,000. Both sets of data differed slightly, but they both included the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) number, the name of the lender, certain demographic data, number of jobs retained and the type of business entity (corporation, LLC, etc).

Combined, these files included records on over 4.8 million individual loans made by banks since the PPP began. Use the table below to see what top lenders made PPP loans in your community.

Total Number of PPP Loans by Lender

Use the filters to see which banks were the most active in your community.

This data is vital because we have very little information about business lending in the United States. In 2010, the Dodd-Frank Act required the Consumer Finance Protection Bureau (CFPB) to collect data from lenders on lending to businesses. Ten years later the California Reinvestment Coalition (an NCRC member) finally won a court case to compel the CFPB to do just that.

Problems with the Data

Unfortunately, missteps by Secretary Mnuchin, the Treasury Department and the SBA have made the data largely unusable by the public and consumer advocates.

To begin with, in the initial loan application form, the SBA did not ask for any demographic data from PPP applicants. This is a radical departure from normal SBA practice, and it leaves the collection of this vital data up to the individual lender.

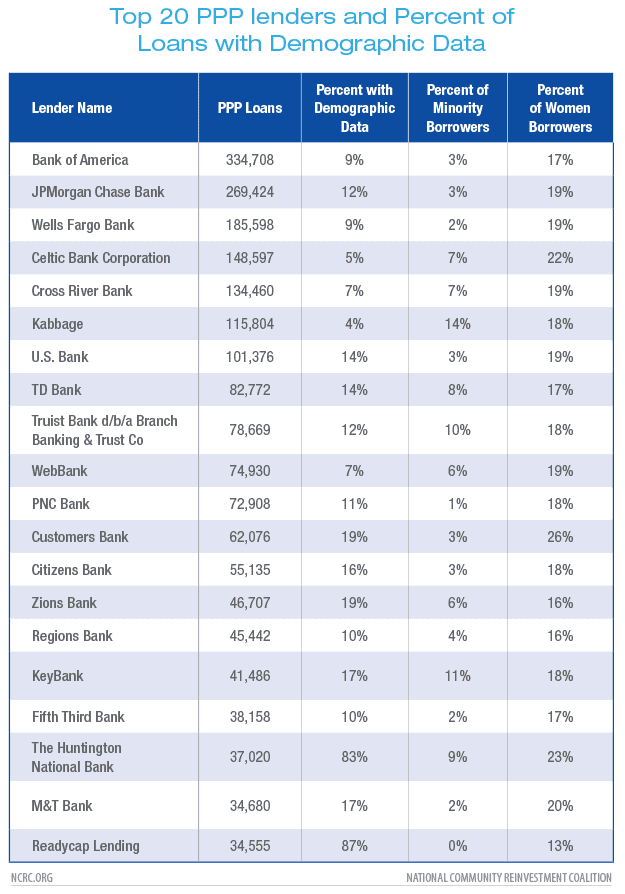

As a result of this, just 23% of the loan records included race or gender data. Much of the data collected is incomplete, with either gender or race but not both. The collection of this data varies widely by lender as well. Among the 20 lenders that made the most loans, Huntington National Bank reported demographic data on 83% of their loans. By comparison, many of the top lenders reported data on less than 10% of loans.

This means that the data is not a representative sample, but heavily favors those lenders that prioritized collecting vital information about who they were making loans to. The lapse in data collection by the Treasury department and SBA means that we are largely blind to the efficacy of the PPP program to reach small businesses in every community.

The SBA has included a demographic section on their application for loan forgiveness. But this form is at the end of the application and lacks clear directions to help borrowers understand how to fill it out. This is in stark contrast to the normal SBA practice seen in the 7(a) lending program, where demographic information is collected at the time of application.

In addition, the Treasury department made specific choices in how they released the data that reduce its effectiveness. Race and ethnicity data has been combined, eliminating any chance of measuring the impact of PPP lending on borrowers of mixed ethnicity or race. The racial categories do not allow for the disaggregation into specific and critical sub-groups. The Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA) data that the Consumer Finance Protection Bureau collects on mortgage loans allows borrowers to select from several different racial sub-groups such as Mexican or Chinese. Over 60% of eligible mortgage applicants in 2019 identified with one of those groups. The SBA data would be better if it allowed business owners this capability.

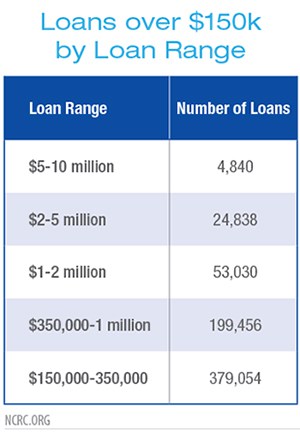

The data is inexplicably subdivided into one dataset of loans over $150,000 and individual files at the state level for smaller loans. For larger loans, the exact amount of the loan is not available, instead the loans are grouped into five large ranges.

The impact of this can be seen in the chart below. Overall, loan volumes can only be determined within broad ranges, which produce a grossly inaccurate picture of actual lender performance. For example, we know from the report released by the SBA that JPMorgan Chase made just over $29 billion in PPP loans, more than any other lender. But as the chart below shows, using the data released by the SBA and the Treasury, we can only determine that JPMorgan Chase made between $22 billion and $42 billion in total lending . For anyone who wants to analyze lending at the local level, or for smaller lenders not itemized in the SBA report, this data is useless.

Total PPP lending by lender

Total amount loaned is indicated by the range in blue. Hover over this chart for more information.

The Treasury department also greatly reduced the ability to use this data by redacting other information that is normally available to the public from the SBA. Smaller businesses were identified only at the ZIP code level, which is too broad to determine if those loans were made in low- and moderate-income (LMI) or minority communities. The standard for this level of data is to redact the address of the business but include the census tract location, which allows much more precise measurement of what communities are receiving these loans without raising privacy concerns. Many of the records lack business names or other information, which further raises concerns about the veracity of these applications. Even though most loans do include the business name, many businesses share the same name. Without a unique identifier, such as a tax ID, it is impossible to properly identify businesses that received a PPP loan with a high degree of certainty.

In addition, lenders are identified only by name, making it nearly impossible to understand if large banks, community lenders or non-banks have been more successful at reaching hard hit businesses.

Most egregious perhaps is that the Treasury department did not release the loan application records, making it impossible to determine whether businesses owned by people of color or women were denied loans more than other applicants.

All of these choices reduce the ability of the public to determine if the loans were broadly available to those businesses most in need.

Analysis

The lack of data creates a gap in our understanding of PPP lending and presents a challenge for understanding the impact of this program on communities traditionally excluded from access to business capital. However, due to the size of the program, even this offers a glimpse of the challenges faced by women and minorities who need access to business credit. NCRC has combined the files released by the SBA, including the state level files for loans of less than $150,000 and the national file for loans over that amount. While the smaller loan files include exact loan amounts, the larger loans are combined into five relatively large ranges based on the amount of the loan.

In this analysis, we have combined the absolute figure of smaller PPP loans with the range of amounts from the larger loans for a total range of lending that was made under this program. This limitation to the analysis is a result of the lack of specific loan figures released by the SBA.

Based on the NAICS codes included with each loan, we have identified the top industry sub-sectors that received PPP lending between April 3,2020, and June 30,2020.

Total PPP lending by industry subsector

Total amount loaned is indicated by the range in blue. Hover over this chart for more information.

More data on the industry sectors can be found here. https://www.census.gov/eos/www/naics/

Professional, Scientific and Technical services is a sub-sector that includes doctors, lawyers, accountants, dentists and many other highly compensated workers. This is generally the sector that received the most PPP lending in most geographical areas. Depending on the specific area of interest, the other major sectors include construction trades, restaurants, religious organizations and healthcare.

Lending to women and minority-owned businesses is a particular concern to NCRC and our member organizations. The overall lack of demographic data in a properly collected and presented format is a significant barrier to analysis. Overall, 1.1 million loans have some form of demographic data, yet we find that this varies widely by lender.

Top Lenders By the Percentage of Loans to Women and Minorities

Hover over the data for more information, including the percent of loan records with demographic data. Use the filters at the top to select a State, ZIP code or Congressional District.

The chart shows the 200 lenders with the most PPP loans total, and the percent of those loans to women and minority business owners.

Discussion

COVID-19 has halted business activity worldwide and is expected to severely curtail most businesses for some time. The PPP program is, at this time, the sole means by which we are offering support for small businesses and their employees. Though highly flawed, among the 1.1 million loans where demographic data exists, 25% indicated that the business was owned by a woman and 21% were owned by a minority. These figures are roughly equal to the number of businesses owned by women and minorities, according to the SBA. This suggests that PPP lending might be finding its way to businesses that truly need it.

Yet, the poor quality of the data and its paucity call these figures into question. The utter failure of the SBA to properly collect data on the borrowers and then to redact both the amount of the loan and the location of the business makes it impossible to track where the PPP money is going and what communities are reaping the benefits of it. The lack of loan application data prevents us from analyzing origination and denial rates. These choices by the SBA contravene its established practice in the 7(a) loan program, where detailed loan level data is available to the public for all borrowers.

Anecdotal data from NCRC members and our experience with testing and other research suggests that many of the loans missing demographic data were made disproportionately to White males.

SBA should implement changes to the program to encourage lenders and applicants to report demographic data both on the loan forgiveness form that they will be completing as well as on the application of any future PPP funding. Many lenders collected this data on a large share of their borrowers, which shows that applicants are willing to report this data.

SBA should immediately implement the following changes to protect the public interest and better support lending to underserved communities;

- Follow the SBA 7(a) program policy of collecting demographic data at the time of application for PPP loan forgiveness and for any future rounds of PPP lending that Congress might authorize and ask current borrowers for this information now.

- Establish clear directions to applicants to correctly identifying the race and gender that should be reported for their business, including in cases of partnerships or corporations where a group of people share responsibility for managing the business.

- Release the records for loan applications that did not result in an origination with the same information as those that were originated.

- Include the exact loan amount authorized by the SBA for all applications.

- Include the EIN or tax ID of the applicant or other unique identifier such as an LEI number so individual businesses can be properly identified.

- Provide census tract locations for the primary business location on each loan.

- Include an identifying number for the lending institution, such as the RSSD ID issued by the Federal Reserve so the type of lender and their size can be known.

Jason Richardson is NCRC’s director of Research & Evaluation.

Jad Edlebi is NCRC’s GIS specialist.