An NCRC evaluation of small business loan applications from a sample of seven banks in Washington, DC, revealed that some lenders discriminate against applicants who have been charged at any time in their lives with a criminal offense. An applicant is considered a lending risk for having been “ever charged” with any crime, other than a minor vehicle violation, no matter when it occurred. This practice is not only factually suspect, it is discriminatory.

There is an important distinction between being charged with a crime and being convicted of a crime. A conviction occurs when a person is found guilty of committing a crime by a judge or jury, or pled guilty. Being charged with a crime means there is evidence for a prosecutor to say that the defendant has possibly committed a crime, and to then have that evidence evaluated by the court system. People are often charged with crimes to later have them dropped, or they are found not guilty.

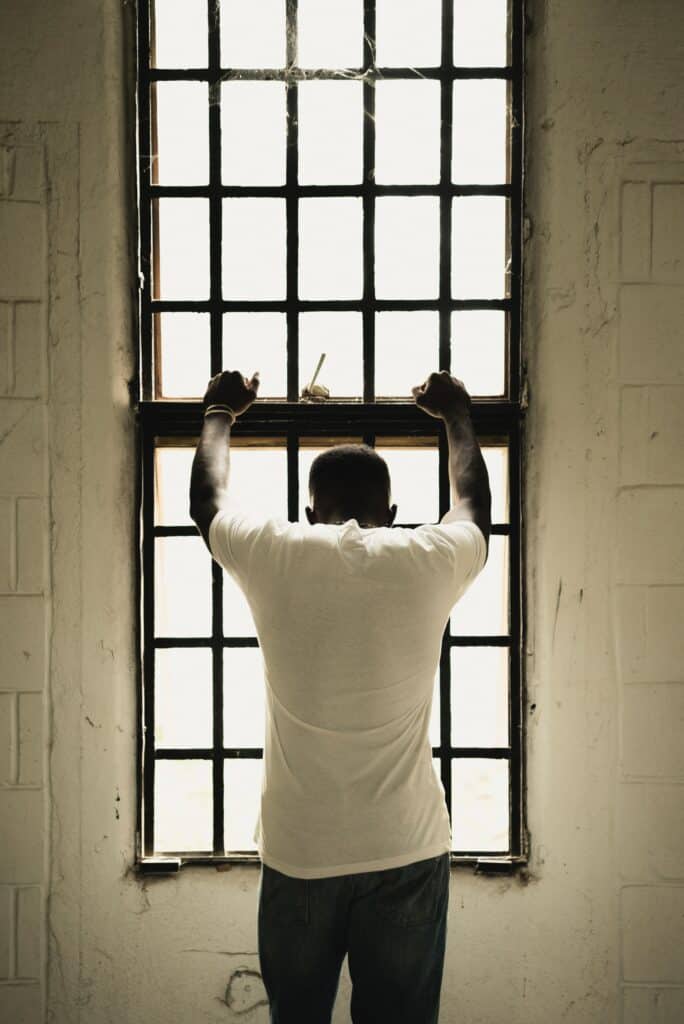

Interactions with the justice system have lasting implications. It is known that having a criminal record is a barrier to both housing and employment. There are few protections for people with a criminal record.

But what about for people who have been charged and found not guilty, or their charges were dropped? What barriers do they face? Unfortunately, they face similar barriers as people who have a criminal record, especially in the small business lending arena.

Small business loans administered by the Small Business Administration (SBA) have broad criminal history restrictions. Analysis conducted by the Collateral Consequences Resource Center (CCRC) found that no statute requires criminal history to be used as a factor in determining creditworthiness. Instead, the Small Business Act uses the words “may verify the applicant’s criminal background.” Furthermore, many restrictions that the US Small Business Administration (SBA) implements on interactions with the justice system are not codified. These restrictions are “either unannounced or only disclosed through FAQs published on the agency’s website…..[or] through policy statements and application forms.”

Some commercial loan applications require an applicant to answer yes or no to a question about their criminal history. The question asks the applicant if they have “ever been charged with a crime.” This language is too broad and violates the Equal Credit Opportunity Act. This language does not recognize situations where charges were dropped, or the person is found not guilty. For these types of situations, the applicant would still be required to respond yes. Otherwise, they are lying on their application, resulting in the applicant not qualifying for the loan. This question violates fair lending laws for the following two reasons.

- It causes a disparate impact based on race

- It discourages applicants from applying

Disparate Impact

Disparate impact occurs when a neutral policy has a disproportionately negative effect on a protected class. The disclosure language “ever been charged…for any criminal offense” results in a disparate impact on the protected status of race for Black applicants. Black people are disproportionately charged for crimes at a higher rate than White people. The New York Times highlighted that “African-Americans make up only about 6 percent of San Francisco’s population, [yet] they accounted for 38 percent of cases filed by prosecutors between 2008 and 2014.”

This disclosure language includes people who are falsely charged. More Black people are falsely charged than White people. The NAACP found that “[a]s of October 2016, there have been 1900 exonerations of the wrongfully accused, 47% of the exonerated were African American.”

Furthermore, the language on these applications does not distinguish between: a felony vs. a misdemeanor; the type of crime committed like a financial crime vs. assault; if the applicant was a minor when the crime was committed; or length of time since the crime was committed.

Financial institutions will assert a business justification for criminal history as it can significantly impact a person’s ability to repay the loan. Under the effects test, financial institutions can fulfill this business justification in a less discriminatory manner by adding language that does not leave the time period open-ended, distinguishes between a felony and a misdemeanor, distinguishes if the applicant was a minor at the time the crime was committed, and provides a list of crimes that require disclosures.

Discouragement

The presence of this question can result in potential applicants being discouraged from applying. Discouragement occurs because applicants believe that answering this question will deny them credit. Therefore, they do not apply. Discouragement is a form of discrimination under ECOA and its implementation of Regulation B, section 1002.4(b).

Moving Forward

Financial institutions need to review their applications to ensure that they are not violating fair lending laws. But this is only part of the solution. Fair lending compliance programs need to ensure that when criminal history is used for credit decisions, its use is narrowly tailored in both time limit and specific crimes that are connected to financial risk, money laundering or terrorism. Financial institutions should not harm potential applicants who are creditworthy simply because they had some engagement in the past with the criminal justice system.

Anneliese Lederer is NCRC’s Director of Fair Lending.

Photo by Karsten Winegeart on Unsplash