The Alzheimer’s Association describes dementia as “a general term for loss of memory, language, problem-solving and other thinking abilities that are severe enough to interfere with daily life.” Dementia is a global health crisis affecting nearly 55 million people.

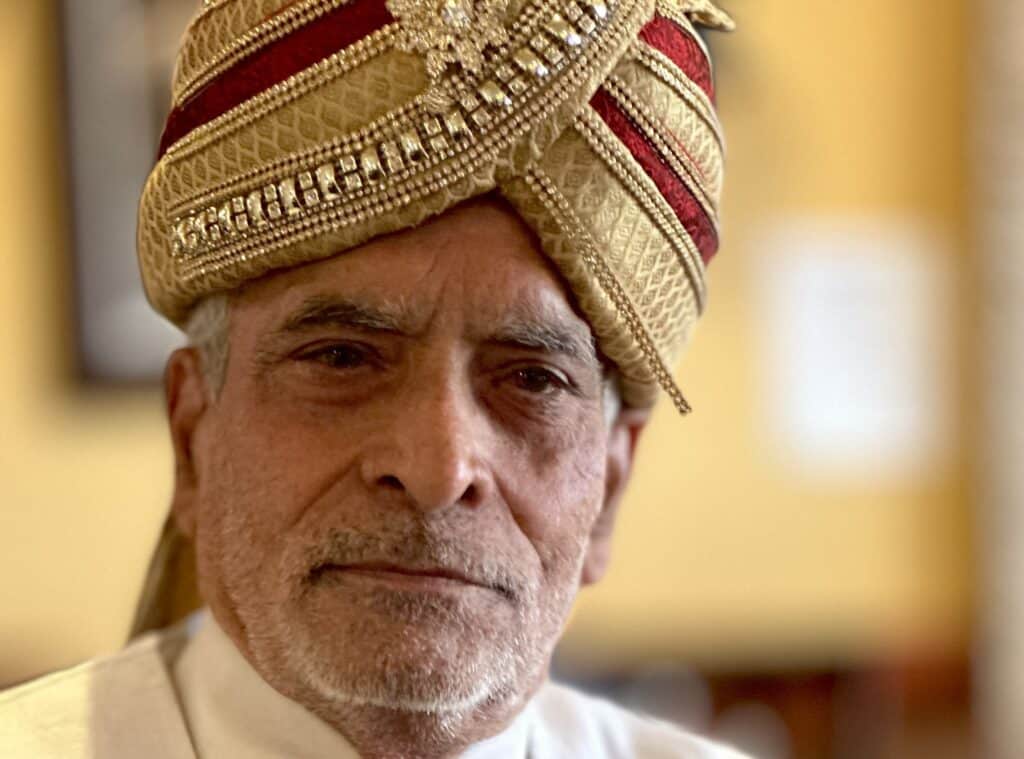

My father, an entrepreneur who ran a small community grocery, liquor store, and deli for half a century, was recently diagnosed with frontotemporal dementia (FTD), which causes a particular decline in behavior and personality.

My father’s diagnosis weighed heavily on my family. It seeped into the cultural fabric of our lives as Indian Americans. As we wrestled with the challenges of my father’s dementia and its manifestations, we found ourselves entangled in the complexities of Indian culture, the stigmatization of this neurological condition and the lack of understanding of the disease.

Last year, my father spent three months living with me and my family in Washington, DC, affording me a rare opportunity to reconnect with him. This time was bittersweet. Dementia seemed to transform my father into an unfamiliar figure at times, subject to bouts of irritability, confusion and restlessness.

I found myself assuming the role of a caregiver, a position familiar to approximately one-fourth of Alzheimer’s and dementia caregivers in the so-called “sandwich generation.” Juggling the responsibilities of caring for my father and two children became an overwhelming challenge, prompting me to take a leave of absence from my professional responsibilities. Realizing the limitations of my caregiving abilities, I began to research alternate elder care options.

I explored private home care service agencies that matched a Certified Nursing Assistant (CNA) with our family needs. The goal was to keep my father as independent as possible. I quickly found that home care didn’t support the spectrum of care needed for my father.

As I continued my search for care options, I found limited and costly senior living communities tailored to my father’s unique situation. Assisted living communities carry a high price tag and the cost of memory care is even greater. Many Americans experience financial ruin because of unsustainable elder care costs. And for immigrant families – even those who succeed in the uphill battles of small business ownership and maintain a healthy balance sheet for decades – that risk is compounded by the lack of financial literacy and planning that I have written about before. Despite a lifetime of hard work, I was afraid my parents could be headed down a financially challenging path, especially considering the unreliable nature of healthcare in the United States and their lack of long-term care insurance.

Navigating my father’s care was a costly maze. I visited nearly fifteen senior living communities and uncovered a system ill-equipped to handle high-functioning yet supervision-dependent individuals living with dementia. The lack of guidance from medical professionals, social workers and senior living community sales directors left me feeling more isolated and confused than when I began this journey. The Alzheimer’s Association became my lifeline; it emerged as an indispensable source of support, connecting me to experienced counselors, research, and education.

The decision to place my father in a senior living community became a careful and thoughtful choice aimed at prioritizing the well-being of my entire family. It was about preserving my father’s dignity and ensuring that he received the best care possible.

I hope that by sharing my personal experience, we can ignite conversations about the broader issues surrounding dementia care – from cultural sensitivities and the caregiver’s burden to unsustainable financial costs and systemic inadequacies in elder care. As we confront this global health crisis that affects millions, it is imperative that we collectively work towards a more compassionate, accessible, and supportive framework for individuals living with dementia and their families.

Monica Grover is the Director of the Executive Office at NCRC.

Photo courtesy of the author.