This essay is part of a series that accompanies NCRC’s 2019 study on gentrification and cultural displacement. The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the views of NCRC.

Gentrification is a policy-driven process that begins with targeting low-income, urban communities for discrimination and neglect and ends with “improvements” that exacerbate vulnerabilities that culminate in displacement, according to conclusions offered by historians and social scientists who have examined the role of racist, housing discrimination – specifically redlining, restricted covenants and blockbusting.

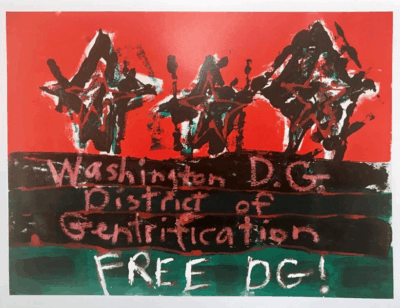

Generated and subsidized by public and private sector coalitions, gentrification is also a form of uneven development that benefits influential segments of urban populations.The tens of thousands who have migrated to the Washington, D.C., over the last five years live in a city that rolled out the proverbial red carpet for their arrival. Infrastructure has been altered, public property has been privatized, the will of voters has been rescinded, minority-owned businesses have been shuttered and the bodies of people of color have been stopped and frisked to accommodate and enhance the respective presence and comfort of newcomers.

Shifting neighborhoods: Gentrification and cultural displacement in American cities

- Overview

- Read the full report

- Interactive map and stories

- Local view: Philadelphia

- Local view: Portland, Oregon

- Local view: Richmond, Virginia

- Local view: Washington, D.C.

- Download the full report (PDF)

Dog parks, bike lanes, condominiums and expensive restaurants now predominate along the local landscape, but these additions are not viewed as assets across the board. Variations in cultural practices intersect with social hierarchies to differentiate views on what does and does not constitute a community benefit. Meanwhile the hopes, dreams and needs of low-income and working class residents – which include truly affordable housing, safe and reliable child care, food justice, the ability to attend houses of worship and the unencumbered use of public spaces – do not diligently appear on the local legislative body’s list of pending priorities.

It is within this context of governmental insufficiency and asymmetrical assistance where studies reveal that the false promises of “trickle-down” economic policies are emerging. Since 2000, the gap between the highest- and lowest-income earners in the city has ballooned. A quarter of the children living in Washington live in poverty[1] . As irrefutable as these numbers are, statistics only reveal a portion of gentrification’s impact. The qualitative data that social anthropologists gather as we sit in the kitchens, living rooms and backyards of long-term residents, tell uniquely compelling stories of alienation and vulnerability in the nation’s capital.

Becoming estranged from one’s home place is a process that unfolds gradually. It happens when low-income and/or residents of color lose more than they gain from top down redevelopment. When trusted and relied upon local businesses close or relocate, crucial services and outlets for sociocultural expression evaporate. Pro-gentrification strategies also thwart access to convenience for low-income residents, creating additional errands and expenses for the heads of households in the gaps left by the loss of neighbors and social networks. As the assistance of trustworthy neighbors disappears, both ephemeral and tangible damages to belonging are generated and forms of isolation begin to proliferate.

On the public housing front, the specter of demolition hangs over populations living in the most affordable accommodations that the city has to offer. Residents of Section 8’s Brookland Manor in Northeast, Greenleaf in Southwest and Park Morton in Northwest are all contending with a capricious housing market as developers drive to create more high-income housing that disregards the pre-existing, socio-economic diversity within their communities.

The Barry Farm housing complex is emblematic of these issues. This historic community was built in the 1940s for lower income families, including those displaced by nearby construction. Over decades, it was home to a broad spectrum of people, including employed and unemployed persons, the disabled, recipients of college degrees, large families, returning citizens and elder retirees. In 2013, Empower DC and residents organized to oppose the planned redevelopment of Barry Farm, which today sits in a prime location near the metro with easy access to downtown D.C. The demolition of Barry Farm threatens to displace hundreds of families that have no other place to go with only a vague promise that they will have a spot in one of the few affordable units that will remain after redevelopment.

Across the city, as the threat of displacement looms for these diverse populations, public housing residents also face unaddressed and unsafe conditions associated with pest infestations and leaking pipes, as well as humiliating forms of over policing that criminalize young people’s use of shared, outdoor spaces.

Low-income residents are particularly vulnerable but moderate-income Washingtonians of color are also at risk for displacement. Decades of job and housing discrimination have fostered a segmented work force hindering the ability of all African Americans to accumulate wealth — that invisible resource that can be a key mitigating factor preventing displacement.

The unfairness has not gone overlooked by Empower DC, the organization for which I work as membership and political education coordinator. Empower DC is a city-wide, membership-based grassroots organization that operates on a community organizing model. Our goals include improving and preserving public housing, preventing the displacement of residents, promoting community-based development and fighting for environmental justice. As one of six staff, we work to establish relationships with directly affected residents in order to build their capacity for leadership by harnessing their collective power and fostering self-confidence.

As an Empower DC staff-member and urban anthropologist with decades of activism and qualitative research under my belt, I have observed the dire impacts of inequality and gentrification first hand. Since powerful public and private forces are aligned against the collective efforts of anti-gentrification/anti-racism organizers, our work continues. The severely alienated and acutely vulnerable are among the descendants of early Washingtonians – women, men and children whose forebears left the southern farms and domestic sphere in search of freedom and opportunity. These are Empower DC members – laborers, teachers, medical assistants, social workers and so many others — including the legions of the unemployed. We are in this fight with them for the long haul!

Dr. Sabiyha Prince, cultural anthropologist, author, artist and activist who currently coordinates membership and political education for Empower DC; @SabiyhaP

[1] https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/education/it-feels-great-to-go-back-the-districts-students-return-to-school/2018/08/20/e2d4f528-a491-11e8-8fac-12e98c13528d_story.html?utm_term=.a5d45988cd4c

Photo by Charles Etoroma via Unsplash

Involuntary displacement is a terrible thing. In most of the country, it manifests itself as “demolition by neglect.” Indeed, this was the predominant form of involuntary displacement in DC until DC became one of the few places in the country to have a robust job market, particularly for high-tech and intellectual workers. Then gentrification took hold, first in white working class neighborhoods in Ward 3 and then moving east. In some neighborhoods (like Shaw), demolition by neglect had removed most of the low-income and working-class folks before the affluent folks moved in.

Although some people think that demolition by neglect and gentrification are totally different, they have a common foundation. That foundation is land speculation. Land speculation is a parasitic activity that creates nothing of value. But it inflates land prices, pushes affordable development away from good schools and transportation, and creates periodic booms and busts in the economy which are horrendous for most residents and businesses.

For info about a cure, see http://solidgroundcampaign.org/blog/want-affordable-housing-look-land .