Kelsey Lyles

Program Manager, Health Equity, The Greenlining Institute

As Health Equity Program Manager, Kelsey Lyles leads the Health Equity team’s workforce equity and inclusion advocacy efforts. Growing up in Chicago, she felt a strong commitment to social justice at a young age. Kelsey has extensive experience in public policy development, cross-sector collaboration, public health program design, and stakeholder engagement strategies. Prior to Greenlining, Kelsey was an Equity Specialist at the California Strategic Growth Council and managed a racial justice capacity building program for California state employees, with participation from 19 departments and agencies. Kelsey also served as a member of the California Health in All Policies staff team for five years, where she led multi-sector state government work groups, developed equity-focused work plans, provided health equity trainings, and promoted a culture shift towards equity and inclusion in state government. Kelsey received her bachelor’s degree in Sociology and Community Development from Howard University.

Adam Briones

Adam Briones, Director, Economic Equity, The Greenlining Institute

Adam Briones leads Greenlining’s banking, housing and economic development work. Prior to joining Greenlining, Adam was most recently a Vice President of Real Estate Development at the Genesis Companies in New York, one of the city’s most active African American-owned affordable housing developers. Previously, Adam was a Senior Analyst for HR&A Advisors, a leading national consulting firm specializing in real estate and economic development advisory services. Before that, Adam was a Housing Fellow with New York City’s primary affordable housing finance agencies, the NYC Housing Development Corporation and the Department of Housing Preservation & Development. Adam has also interned with the office of Congresswoman Maxine Waters and the House Financial Services Committee in Washington D.C. as well as with the community development finance group of a major California lender. Adam began his career at The Greenlining Institute, where he worked from 2006 to 2010 on issues including affordable homeownership, transparency in philanthropy, redistricting, and national banking policy. Adam holds a Master of Urban and Regional Planning from the University of California Los Angeles with a concentration in affordable housing development and finance and earned his Bachelor of Arts in Anthropology from UC Santa Cruz.

This is one in a series of essays accompanying NCRC’s 2020 analysis that showed more chronic disease and greater risks from COVID-19 in formerly redlined communities. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views or policy positions of NCRC.

By every measure, COVID-19 has exposed the structural inequality that communities of color face in our country. Here in California, African Americans and Latinos suffer disproportionately and data from the State Public Health Department shows that African Americans, Latinx and Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islanders over age 18 are dying at disproportionate rates. Across the U.S., we know that African American and Latinx deaths far exceed the average and even other communities of color.

We also believe that the true impact on Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) communities, especially immigrants, is being underestimated by a lack of clear data. Unfortunately, diverse and disparate Asian American communities still get lumped together in an artificially homogenous way that distorts the real impact of issues like income inequality, mortgage access and redlining on specific communities.

The COVID-19 pandemic has also created an economic crisis. While to date more than $650 billion has been set aside for federal small business support, estimates project that less than 10% of those funds will reach businesses owned by people of color. Based on anecdotal evidence, Greenlining believes that figure is closer to less than 5% in California. What makes this so tragic is that a decade ago, it was businesses owned by people of color that, despite suffering more than other businesses, carried our economy forward and out of the worst years of the Great Recession.

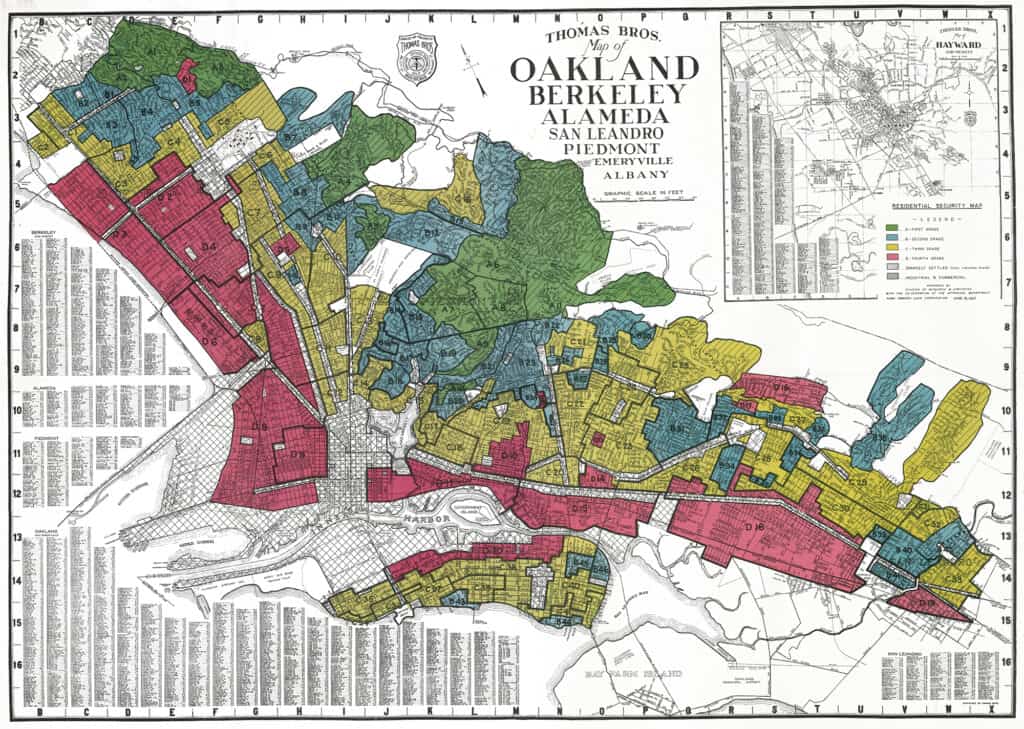

Unfortunately for California, this health and economic disaster is converging with an older, more insidious man-made disaster: redlining. For those unfamiliar, redlining is the historic practice where literal red lines were drawn around non-White communities by both public and private mortgage lenders and insurers in order to show that these areas were unsuitable credit risks. Of course, this designation was not based on economics or reality, but skin color and racist perceptions of non-White neighborhoods.

Even after explicit redlining ended, these targeted neighborhoods suffered disproportionately from lingering economic and social disinvestment. A newly released report by the National Community Reinvestment Coalition has found that more than a half-century after the practice became illegal, redlining lives on not just in our communities’ economies but in our communities’ bodies as well. The report found data to show statistically significant associations between greater historic redlining and increased rates of poverty, social vulnerability, high cholesterol and poor mental health.

Further, greater redlining was found to be correlated with pre-existing conditions for heightened risk of morbidity in COVID-19 patients like asthma, diabetes, hypertension, kidney disease, obesity and stroke. Perhaps most striking is that historic redlining has literally shortened the lifespans of families living in those neighborhoods today. On average, life expectancy at birth is reduced by more than three years in communities that experienced redlining.

Despite the fact that we know laws first passed a century ago are helping to drive poverty and inequality today, reparative policies targeted directly at the communities most harmed are outlawed in California due to Proposition (Prop.) 209. Prop. 209 passed in 1996 as part of a wave of regressive ballot initiatives that also included Prop. 187 (eventually blocked by the courts) which took away public benefits from undocumented immigrants, Prop. 227 which established English-only classrooms and Prop. 184 (“3-Strikes and You’re Out”) which filled our prisons, often with Black and Brown men accused of nonviolent offenses.

Prop. 209 is one of the last major remnants of this embarrassing period in California’s history and now more than ever we need to rebuild a 21st century California that reflects the values and diversity of our communities. We need to unite to put an end to the effects of redlining and ensure everyone has a fair shot in our state.

This November, California’s voters will have the opportunity to repeal Prop. 209 by voting Yes on Proposition 16. Redlining was expressed through geographically targeted policies, but the cancerous notions underlying redlining laws were always based on race and White supremacy. California needs to be able to consider race, ethnicity and gender when allocating resources and making public policy to ensure that folks that are most impacted by COVID-19 and systemic racism receive the support they need.

Californians deserve a state with public policies based on data, research and reality. To ensure that the sickest and most in need receive attention, we need targeted economic and public health policies. To ensure taxpayer money is well spent, we need the ability to direct scarce funds where they are most needed. To combat the lingering effects of redlining that show up in our communities even today, we need to pass Proposition 16.