Investing in a Just Economy

For over 27 years, NCRC has worked to create a just economy. We believe private capital of various forms – including a wide variety of financial institutions – must be engaged in building an equitable and fair economy. There is both a legal and a moral obligation for banks and other institutions to invest and lend in low- and moderate-income communities. This is particularly true in the wake of the last financial crisis, as the many borrowers, including African-Americans struggle to access homeownership.[1] The nation continues to rebound from a 40-year decline in business startup activity, and underserved communities struggle to attract private investment.[2]Homeownership remains the best vehicle for low- and moderate-income families and people of color to build wealth and enter the middle class. And small businesses and start-ups are an essential source of new job creation. To ensure the widest and most equitable access to credit across the country, the affirmative obligations, or Duties to Serve, of the nation’s financial institutions must be defended and expanded. Leading experts in affordable housing, Adam Levitin and Janneke Ratcliffe, summarized the vital role the Duties to Serve play:

“Fair lending concerns the obligation not to discriminate on unlawful grounds in the actual granting of credit and its terms. But, the Duties to Serve concept is broader and it recognizes that merely prohibiting discriminatory lending is insufficient to address the disparity of financial opportunity.”[3]

CRA: 40 Years of Fighting Redlining and Defeating Capital Export

October 2017 marked the 40th anniversary of the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA). CRA is an affirmative obligation in the primary lending market. Under CRA, depository institutions “have a continuing and affirmative obligation to help meet the credit needs of their local communities in which they are chartered.”[4] Those obligations are to be met “consistent with the safe and sound operations of such institutions.” The law was enacted to end redlining (the practice of banks refusing to consider mortgage applications from minorities based on the neighborhood they lived in rather than their personal credit and financial situation) and to defeat capital export (banks using the deposits made by persons from low-income neighborhoods to lend to persons in more affluent neighborhoods).[5]

CRA is implemented by the three federal bank regulators (the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, and the Federal Reserve System) through periodic lender examinations of all federally insured depository institutions. These CRA examinations vary in occurrence and detail based on lender asset size, with small lenders under $250 million in assets being evaluated less frequently (usually once every four or five years) and less thoroughly (one test area instead of the three applied to large banks). Upon completion of the examination, regulators award banks ratings based on their compliance with the CRA. Regulators can then use a poor rating to deny lender applications for such things as opening a new office or acquiring another bank.

In 1989, during the congressional debate to make a bank’s CRA rating public, former U.S. Representative Bob Walker (R-PA) repudiated redlining as “an abominable practice” and defended the law as “about opportunity and access.”[6] Rep. Walker’s defense of CRA continues to ring true today. Redlining is not an issue of the past: the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) alone brought nearly $40 million dollars in enforcement actions against institutions for redlining while Richard Cordray served as Director of the agency.[7]

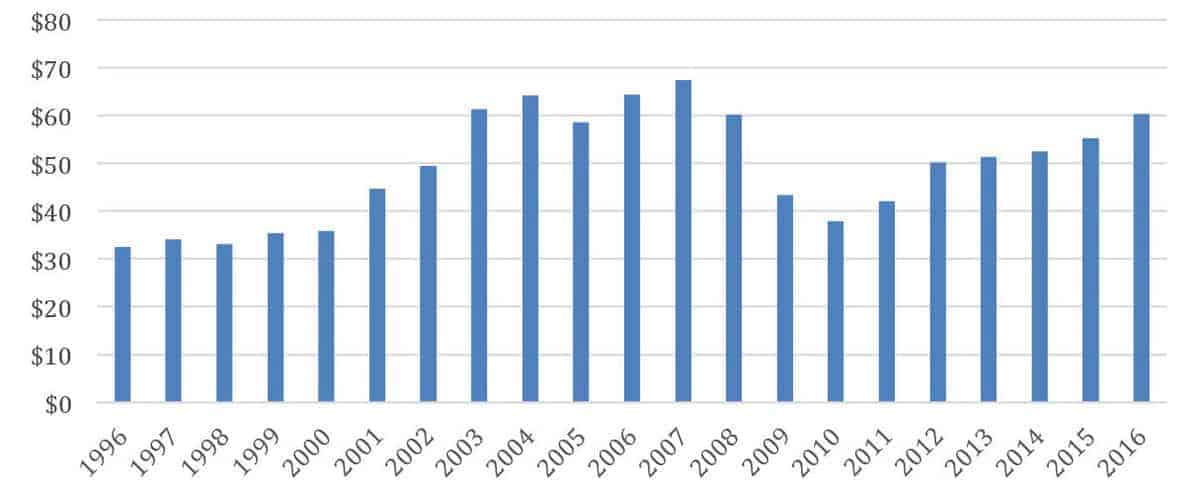

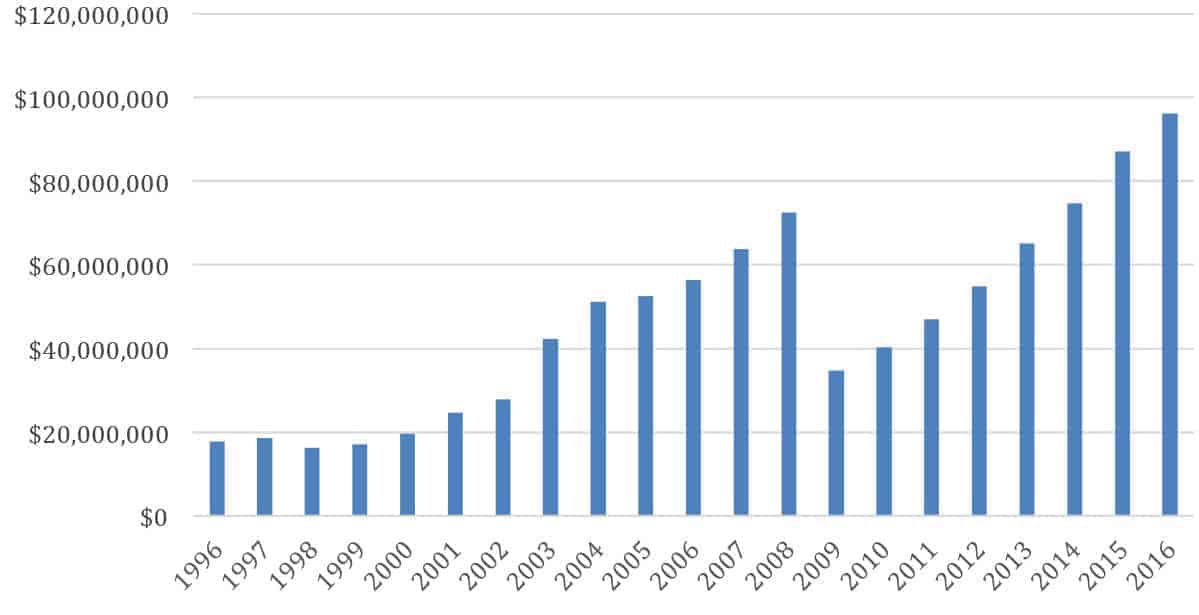

Together with anti-discrimination, consumer protection, and disclosure laws, CRA remains a key element of the regulatory framework for the nation’s banks, encouraging the provision of mortgage loans, small business loans, investments and other financial services in their local communities and for low- and moderate-income neighborhoods. According to data from the Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council (FFIEC), since 1996, CRA-covered banks issued more than 25 million small business loans in low- and moderate-income census tracts, totaling more than $1 trillion (see Figure 1), and made more than $980 billion in community development loans (see Figure 2).[8] Community development loans support affordable housing and economic development projects benefiting low- and moderate-income communities.

Dollar Amount of Small Business Loans in Low- and Moderate-Income Tracts (in Billions)

CRA Community Development Loans

Depository institutions are compelled to meet their affirmative obligation under CRA in exchange for taxpayer support, such as bank charter status and federal deposit insurance.[9] As the financial marketplace evolves, however, it is critical that the playing field be level for all financial institutions. Financial technology companies (FinTech) and other nonbanks have continued to gain significant market share since the financial crisis, doing more and more mortgage and small business lending. These institutions also have a responsibility “to provide fair access to financial services by helping to meet the credit needs of [their] entire community” and “promot[e] fair treatment of customers including efficiency and better service.”[10]

The Affordable Housing Goals

In the secondary mortgage market, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac (the Enterprises) also have “an affirmative obligation to facilitate the financing of affordable housing for low- and moderate-income families…while maintaining a strong financial condition and a reasonable economic return.”[11] The Enterprises have annual affordable housing goals, which require the Enterprises to purchase a set percentage of mortgages to finance single family and multifamily housing for low- and moderate- income borrowers.[12] Their 2018-2020 affordable housing goals require the GSEs to meet the same benchmarks as in 2015-2017, with the exception of the multifamily low-income goal benchmark, which increased from 300,000 units to 315,000 units.

For decades, the Enterprises have provided leadership in developing loan products and flexible underwriting guidelines and have taken other steps to increase the flow of responsible mortgage credit to low- and moderate-income borrowers and communities. For example, the willingness of the Enterprises to purchase three-percent down payment mortgage loans from financial institutions in the primary market over the years has provided homeownership opportunities to millions of working families across the country.

The Duty to Serve Rule, Housing Trust Fund and Capital Magnet Fund

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac have other affordable housing responsibilities as a result of the affirmative obligations in their charters and the law. In January 2018, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac began targeted work to encourage mortgage financing in three underserved markets: manufactured housing, affordable housing preservation, and rural housing. This work stems from a new Duty to Serve rule finalized in 2017.[13] Both Enterprises can receive Duty to Serve credit by developing mortgage products, purchasing mortgage loans, doing outreach and making investments in the three underserved markets.[14]

The Enterprises also dedicate a portion of their revenues to the Housing Trust Fund (HTF) and the Capital Magnet Fund (CMF). The HTF and CMF provide grants to states and state housing agencies and competitive grants to Community Development Financial Institutions and nonprofit housing organizations to increase affordable housing for low-income families and areas.

The Challenge Post-Crisis and in the Current Political Climate

NCRC and consumer advocates are facing enormous challenges in ensuring that low- and moderate- income borrowers and underserved communities have access to affordable and sustainable credit and that homeownership remains accessible. In response to the financial crisis of 2007-2009, many traditional banks have restricted credit to small businesses and homebuyers. Homebuyers, consumers and businesses, for example, have trouble accessing safe and sustainable small-dollar loans. Credit score standards remain extraordinarily high by historical standards, placing homeownership out of reach for many potential buyers. Challenges with access to credit also help explain a 40-year decline in business start-up activity.

In addition, critical trends in the financial marketplace have escalated in the primary lending market. The rising market share of FinTech, including online lending platforms and other nonbanks, have meant that there is a rising segment of the primary market that have no affirmative obligations – no duty to serve low- and moderate-income borrowers in the way that CRA requires of banks. They also have varying levels of legal and regulatory requirements that create competitive advantages in the financial marketplace.[15]

Changes in the nation’s federal tax code and federal budget policies also pressure homeownership, affordable rental housing and economic development. With the passage of federal tax reform in 2017, the nation now has a flatter tax code with fewer direct incentives for low- and moderate-income households to buy a home. A lower corporate tax rate has diminished the value of key tax credits that have long facilitated affordable housing projects and other community and economic development investments in underserved communities. In addition, tight federal spending caps have resulted in cuts and slower growth in domestic programs critical to local community development efforts, such as the Community Development Block Grant (CDBG), Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFIs), and HOME Investment Partnership, to name a few. With fewer valuable federal tax credits and declining “soft subsidies” in the federal budget, it could be far more difficult to finance affordable housing and economic development projects in underserved/disinvested communities.

The Trump Administration and the 115th Congress

The Trump Administration has taken several steps to roll back, undermine and reshape the nation’s financial regulations, including fair lending oversight and enforcement. The U.S. Treasury Department issued three reports on the financial regulations of banks, credit unions and other financial institutions.[16] The Department is also expected to release a set of CRA recommendations. In perhaps an early sign, then-Acting Comptroller Keith Noreika issued a policy change on the 40th anniversary of the CRA that limits the regulator’s ability to downgrade a bank’s CRA ratings for fair lending and other consumer law violations.[17]

In November, President Trump appointed Mick Mulvaney as the Acting Director of the CFPB, and he has taken swift action to undermine the supervisory and enforcement powers of the agency. In one step among many, Director Mulvaney stripped the Office of Fair Lending & Equal Opportunity (OFLEO) of its supervisory and enforcement role. OFLEO had been central to the CFPB’s recent fair lending enforcement actions and multi-million dollar settlements with Hudson City Bank and Bancorp South for redlining. Under the stewardship of its first Director, Richard Cordray, who was appointed by President Obama and served from 2012 to November of 2017, the CFPB’s supervisory and enforcement work provided nearly $12 billion in relief to consumers.[18]

The U.S. Congress is also considering legislation to repeal and limit key provisions of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (Dodd-Frank Act), as well as the related regulations by the CFPB. The Senate passed S. 2155, a bipartisan bill that would undermine several provisions of the Dodd-Frank Act. Among other provisions, the bill exempts the vast majority of the nation’s banks from having to update reporting about their mortgage lending under the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA). Following a surge of predatory and subprime lending in the lead-up to the financial crisis, the Dodd-Frank Act required that financial institutions report more loan-level detail about loan features and borrowers.

Both the House and Senate are considering legislation to overhaul Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac and the nation’s housing finance system in ways that eliminate the affordable housing goals and other key mandates on financial institutions to serve low- and moderate-income borrowers and communities.

With the changing financial marketplace and the new political landscape, NCRC’s advocacy has gained a new urgency: to protect and strengthen the CRA; to preserve the affordable housing goals and the broader affirmative obligations on financial institutions to serve low- and moderate- income borrowers and underserved communities; to ensure enforcement of the nation’s fair housing and fair lending laws; and to protect federal funding for key affordable housing, community development, small business, and social safety net programs.

Invest Local

The duty that financial institutions have to invest in their communities must be expanded and enforced. The more all financial institutions invest in and serve the local economies where they sell their products and services, the more those communities can keep financial resources circulating through their businesses and neighborhoods, building wealth and prosperity for years to come.

Invest Forward

Building community prosperity requires a long-term plan to expand and preserve access to credit and capital. We must commit to thoughtful legislative and regulatory reforms and promote policies that not only stabilize our communities, but also position them for future growth. As more lending shifts to online platforms, nonbanks, credit unions and others, the challenge is to ensure that all new forms of lending have the same affirmative obligations to serve their communities.

Invest Fair

Every person in a community, regardless of their race, age, or socioeconomic status, should have the opportunity to build wealth. Equal access to financial products and services is critical.

Invest Period

Funding plays a critical role in building community prosperity. The President, the U.S. Congress, regulators, and the financial services industry must continue the nation’s economic recovery by investing in communities.

Invest Local

ISSUE: Defend CRA From Efforts to Weaken it

The Department of Treasury has announced plans to issue a set of recommendations to overhaul the CRA. Community banks and others are once again proposing to raise the “small” and “intermediate small” bank asset thresholds in order to limit the extent and frequency of CRA examinations.[19] Under the Bush Administration in 2004-2005, the federal regulatory agencies amended the CRA regulations to replace comprehensive CRA exams with streamlined exams that focus on the lending and community development activities of intermediate small banks with assets between $250 million and $1 billion (these thresholds adjust annually for inflation).[20]

Financial institutions are also advocating other changes to CRA, such as: allowing banks to get more CRA credit for investing outside their local community and assessment areas; expediting bank mergers and acquisitions in ways that limit community input; changing the CRA Service Test in ways that might place less emphasis on bank branches and more emphasis on online banking; and reducing data reporting requirements.[21] The 2004-2005 amendments to the CRA exams exempted small business from lending reporting requirements for intermediate small banks.

Who Can Act:

The Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), the Federal Reserve System, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), the U.S. Congress

NCRC’s Position:

NCRC opposes any efforts to make exams easier for subcategories of banks. A recent NCRC report found that intermediate small banks issue about $3 billion of community development financing annually, which is a level similar to the Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) program. Further weakening the CRA exams of intermediate small banks would significantly reduce their level of community development financing.[22] NCRC has also found that when exams are made easier, bank activity in underserved communities is reduced, including a decline in the dollar amount of community development lending and investing.[23] Financial institutions of all sizes, including small and intermediate small banks, are also important small business lenders in smaller cities and rural areas.

We also oppose expedited mergers that limit public input from local communities on the impact, and proposals that reduce the emphasis on bank branches as well as banks’ lending and investing in the local communities they serve.

NCRC also opposes any further efforts to lessen data reporting requirements. Without regular access to their small business lending data, CRA examiners, community groups, and interested members of the public cannot hold these lenders accountable for lending to small businesses.

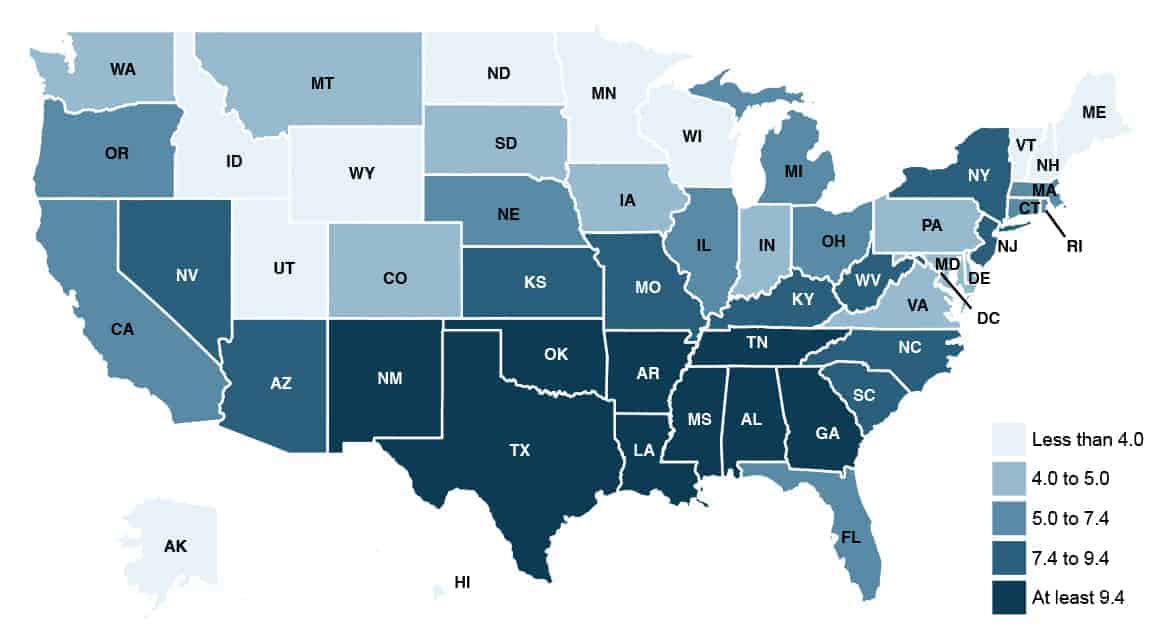

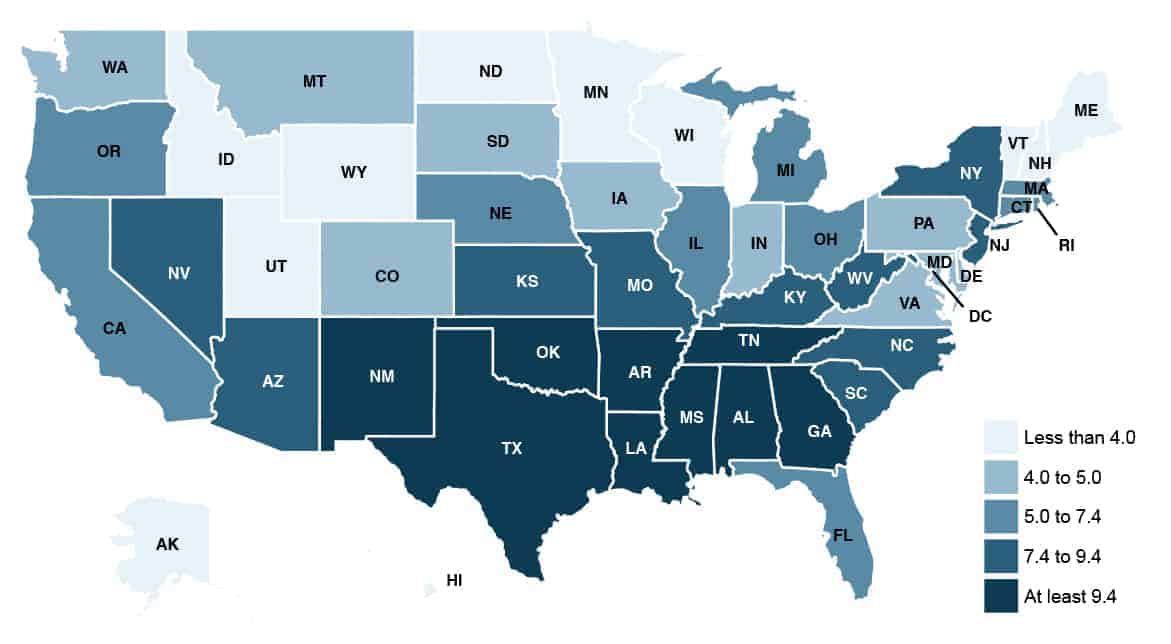

ISSUE: Improve Accountability for CRA Activities With Tougher Bank Examinations and Timely Release of CRA Ratings

CRA is key to driving better basic banking services, increased mortgage and business lending, and improving community development in low- and moderate-income communities nationwide. Across the country, numerous examples of financial disinvestment and malpractice highlight the need for strong enforcement of CRA and improvement in CRA exams and ratings. There is a sizable segment of U.S. households going unbanked and under-banked and relying on alternative financial services (e.g., money orders, check cashing services, pawn shop loans, auto title loans, paycheck advance/deposit advances, or payday loans).[24] (See Figures 3 and 4.) Wide swaths of communities in the U.S. lack adequate small business lending.[25] And recent investigations and enforcement actions by the CFPB and the Department of Justice (DOJ) have exposed ongoing redlining. However, over 98 percent of banks examined by federal regulators from 2012 to 2014 received a passing grade on their CRA exams.[26] In comparison, in the 1990s – a period of significant investment in low- and moderate-income communities – many more banks failed. When ratings first became public in 1990, around 10 percent of banks failed their CRA exams.[27] During the first five years of the public availability of CRA ratings, more than five percent of banks failed their CRA exams every year. That number has steadily trended downward, but the higher ratings are not reflected by the experiences of low- and moderate-income, economically distressed, and rural communities.

Who Can Act:

The Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), the Federal Reserve System, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC)

NCRC’s Position:

CRA examinations should provide a more accurate measure of lending, investment and the provisions of basic banking services in low- and moderate-income communities by ensuring bank examiners:

- Weigh loans originated by a bank more heavily than purchased loans;

- Conduct more rigorous fair lending reviews, and better coordinate with other federal banking regulators and the CFPB;

- Provide easier ways for the public to provide input;

- In addition to analyzing lending in areas with bank branches, examine lending in areas where banks are making significant amounts of loans but do not have bank branches;

- Maintain an emphasis on branches and collect more data on the provision of bank accounts to low- and moderate-income customers;

- Collect better data on the number and percent of deposit accounts and basic banking services that are offered to low- and moderate-income customers;

- Better review for harmful practices (e.g., excessive overdraft fees);

- Examine for loss mitigation practices, particularly with the expiration of the federal Home Affordable Modification Program (HAMP) and Home Affordable Refinance Program (HARP);

- Ensure examinations are conducted regularly and released timely. Of the top 100 banks by asset size, 35 have not had a CRA exam since 2012. Of these, nine have not had an exam since 2010 and seven since 2011. Out-of-date CRA exams contribute significantly to lenient oversight of banks and diminish expectations of continued and affirmative responses to credit needs.[28]

Unbanked Rates by State, 2015

Unbanked Rates by State, 2015

ISSUE: Identify and Enforce Public Benefits Claimed by Banks in Mergers and Acquisitions and Require Specific Description of Public Benefits of Mergers

For 50 years, the law has required federal regulators to consider the public’s interest when approving bank mergers and acquisitions. Both the Bank Holding Company Act and the Bank Merger Act require regulators to consider “the convenience and needs of the community to be served.”[29] Regulators must assess whether mergers provide benefits to the public beyond the gains for financial institutions through increased profits and market power.

If mergers only benefit financial companies while communities suffer through plummeting loan levels, branch closures and increased prices, then society has been made worse off, since inequality will increase, employment will decrease, and economic activity in communities will be depressed.

The only way to assess the potential public benefits of a merger is through a specific and concrete plan described in the bank’s application regarding future levels of lending, investments, and services in low- and moderate-income communities. But the regulatory agencies do not regularly require submission of these plans.

Who Can Act:

The Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), the Federal Reserve System, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC)

NCRC’s Position:

To benefit communities, federal agencies must clarify the public benefit standard so that both the public and financial institutions can better understand this factor’s importance and its requirements. After mergers, regulators must also consistently monitor and enforce banks’ claimed public benefits to ensure that institutions fulfill their promises. The regulatory agencies could:

Offer a template for banks to outline the public benefits of a proposed merger;

Require specific descriptions with verifiable performance measures of how future CRA and fair lending performance will improve. The public must have an opportunity to comment on these public benefit plans during the merger application process.

The merger application time periods must not be shortened for banks with Outstanding ratings as some in the industry periodically propose. Although a bank may have an overall Outstanding rating, its performance in some or many of its assessment areas may not be at an Outstanding level or may have deteriorated since its last CRA exam. The merger application time period must be sufficient to identify and rectify inconsistencies in performance.

ISSUE: Reduce FHA’s Mortgage Insurance Premium to Make Homeownership More Accessible

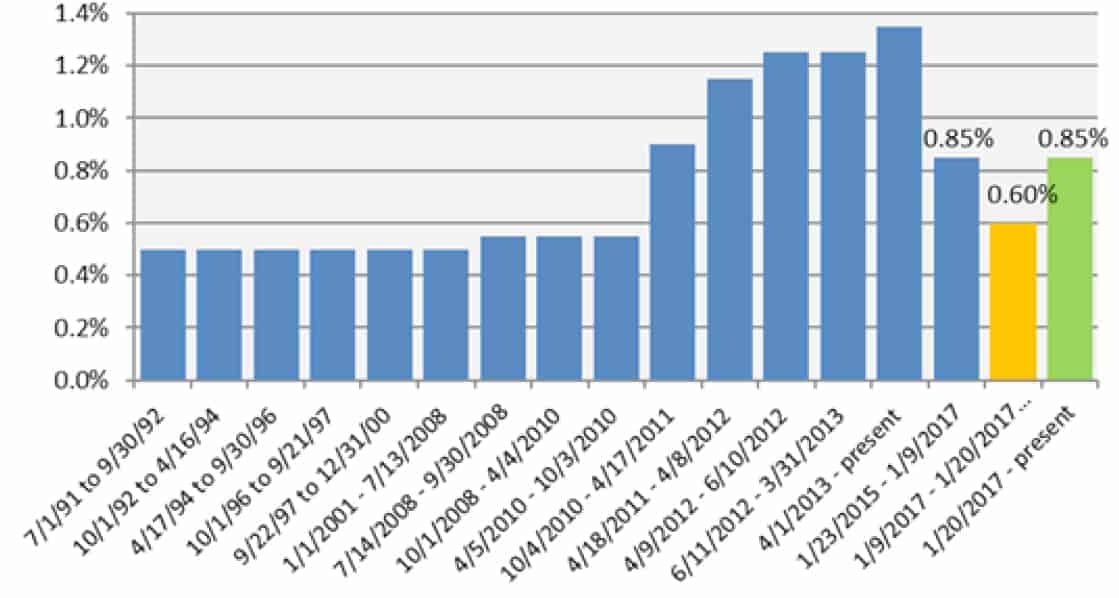

Following the financial crisis, the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) served as the key stabilizing force in the mortgage market that it is intended to be. As financial institutions restricted lending and made it extraordinarily difficult to obtain a home mortgage, FHA stepped in so that many responsible, hard-working, creditworthy Americans had a path to homeownership. Among homebuyers, FHA increased its market share from 4.5 percent of purchase loans in 2006 to 33 percent in 2009.[30] This dramatic increase following the crisis, combined with an economic recession, placed extraordinary pressure on the FHA Mutual Mortgage Insurance Fund (MMI) Fund. In 2010, FHA made the first of several increases to FHA’s Mortgage Insurance Premium (MIP) to shore up the program’s reserves – raising premiums 145 percent (see Figure 5).[31]

As the economy improved, foreclosures declined, and the health of the MMI Fund rebuilt capital reserves, FHA began to reduce their historically high premiums that were limiting affordability for borrowers and almost certainly discouraged some first-time homebuyers from entering the market. In early 2015, FHA reduced the premium that borrowers pay for mortgage insurance, providing an annual savings of $900 for nearly two million FHA homeowners.[32] The National Association of Realtors (NAR) estimated that in 2014, between 234,000 and 255,000 creditworthy borrowers were priced out of the market because of high premiums.[33]

On January 27, 2017, FHA was to reduce the premium that borrowers pay for mortgage insurance closer to historical norms, as the MMI Fund met the congressionally mandated capital reserves needed to pay claims on defaulted mortgages. Upon taking office, the Trump Administration halted the planned MIP reduction. Estimates of the impact of this reversal showed roughly 750,000 to 850,000 homebuyers faced higher costs, and 30,000 to 40,000 new homebuyers would be left on the sidelines in 2017 without the cut.[34] One week after the reversal total mortgage applications fell 3.2 percent, with a 13 percent drop in FHA applications being a strong driver of the decrease.[35]

Homeownership remains the best vehicle for low- and moderate-income families and people of

color to build wealth and enter the middle class. Not only is FHA essential for first-time homebuyers, but it is also central for minority borrowers – both of which are experiencing historic declines in homeownership. FHA has supported more than half of all first-time homebuyers and half of all African American and Latino homebuyers in recent years.[36]

Annual Insurance Rate for FHA Borrowers

Who Can Act:

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), the U.S. Congress

NCRC’s Position:

NCRC urges HUD Secretary Ben Carson to reinstate FHA’s MIP reduction so that homeownership will be within reach of more first-time and underserved borrowers. FHA’s MMI Fund is well-funded and actuarially sound and can support a rate cut.

NCRC also urges Congress to resist efforts to change the accounting treatment or capital ratio of the FHA MMI Fund – either step would further restrict access to homeownership for the borrowers that rely on the program. Congress mandates that the MMI Fund capital reserves must be above two percent. The MMI Fund now stands at $25.6 billion, a decrease of $1.9 billion from Fiscal Year 2016.[37] The program’s capital reserves decreased from 2.3 to 2.09 percent.[38]

ISSUE: Continue to Improve the FHA Quality Assurance Framework to Ensure Greater Lender Participation and Better Access to Homeownership

With its low down payment requirement, the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) mortgage insurance has served as an important pathway to homeownership for first-time homebuyers, as well as many low- income, rural, and minority homebuyers. In Fiscal Year 2015, 82 percent of all FHA purchase originations were to first-time homebuyers and over 33 percent of FHA endorsements went to minority borrowers.[39]

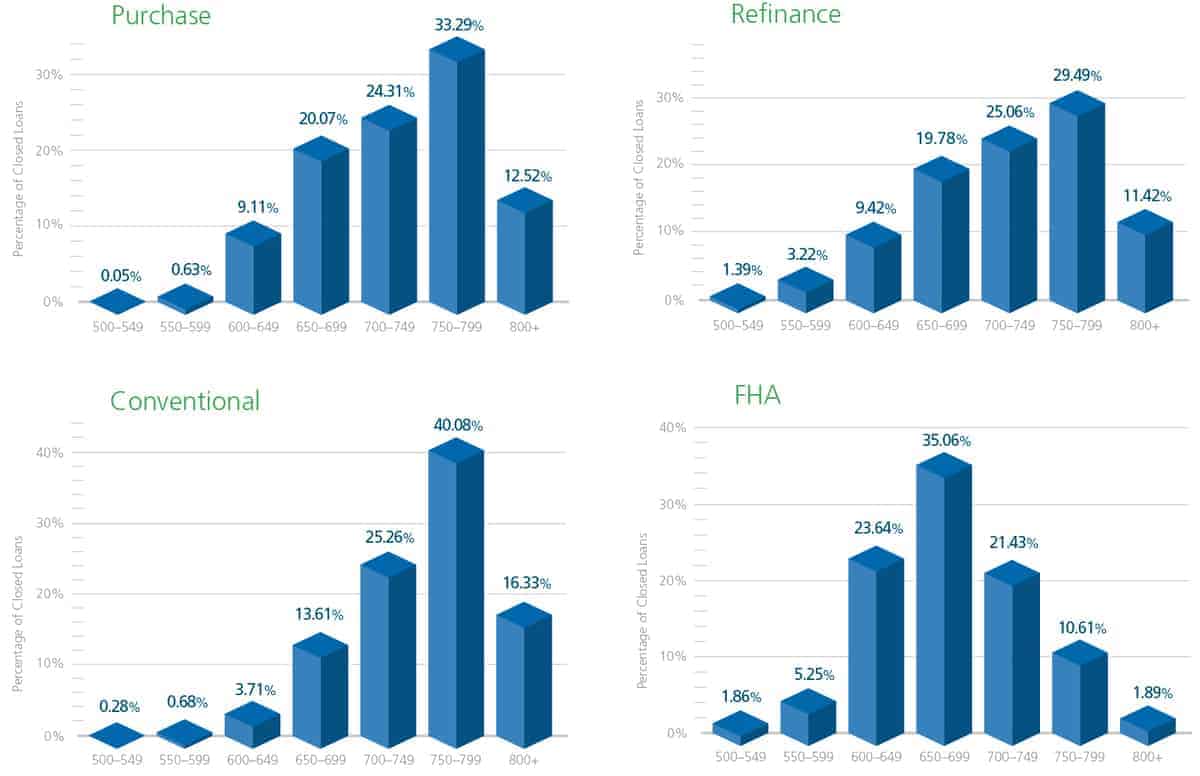

Nonetheless, several large banks around the country have been decreasing their participation in the FHA program and raising their borrower credit score requirements and pricing above the requirements to obtain FHA insurance. In November 2017, the average FHA purchase FICO score was 680,[40] well above the 580 minimum credit score allowed to qualify for FHA insurance (see Figure 6). Nonbanks now dominate the market for home purchase loans insured by FHA. In September 2012, banks originated 65 percent of the purchase-mortgage loans insured by FHA; today, however, that number has more than flipped: nonbanks originate 73 percent of the loans, with banks’ share dropping to 18 percent. The figures are more spectacular for refinanced mortgages, where nonbanks now make up 93 percent of loans.[41]

Lenders have cited three reasons for pulling back from the FHA lending: the risk that they will be required to indemnify or pay back FHA if a loan defaults; the high costs of servicing delinquent loans; and the risk of lawsuits due to recent enforcement actions by both the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) under the False Claims Act and the Financial Institutions Reform, Recovery, and Enforcement Act (FIRREA) that have resulted in large settlements and damages awards.[42]

Who Can Act:

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD)

NCRC’s Position:

FHA should clarify the types of loan defects that will trigger the agency taking enforcement actions against lenders by improving the loan-level certifications and annual certifications that they require lenders to sign. Currently, they contain very broad language, which doesn’t inform those lenders of the type of defects that will trigger liability and enforcement action. FHA has the ability to expand credit access to traditionally underserved borrowers by providing greater certainty for lenders as to which defects will lead to lender buybacks and enforcement action by HUD and/or DOJ.

Improved transparency in loan-level certifications could facilitate strong lender participation in the FHA insurance program and greater access to mortgage credit for borrowers.

November 2017 Average FICO Score Distribution

ISSUE: Protect Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac’s Affordable Housing Mission and Affordable Housing Goals in Any Reform of the Enterprises

Both Sen. Mike Crapo, Chairman of the U.S. Senate Banking Committee, and U.S. Rep. Jeb Hensarling, Chairman of the U.S. House of Representatives Financial Services Committee, have indicated that their committees will once again consider housing finance reform.

Many in Congress have discussed intentions to reform Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac (the Enterprises) and the way the secondary mortgage market functions. The Housing and Economic Recovery Act of 2008 (HERA) enacted the first set of reforms to the Enterprises following the financial crisis, and was the culmination of almost a decade of work by Congress, the Federal Reserve Board and other stakeholders.[43] The law significantly reformed their supervisory and regulatory framework, creating the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA) as Enterprises new regulator. FHFA was given broad new authority over their prudential management and operations, including to set and adjust their capital reserves and to regulate their loan portfolio and the credit risk they take on and hold. Senators Corker and Warner are actively working on legislation to reform Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, and have expressed an intention of moving away from the explicit Affordable Housing Goals for a more incentive-based approach. As it stands, this legislation is insufficient and threatens access to both affordable rental properties and affordable homeownership.

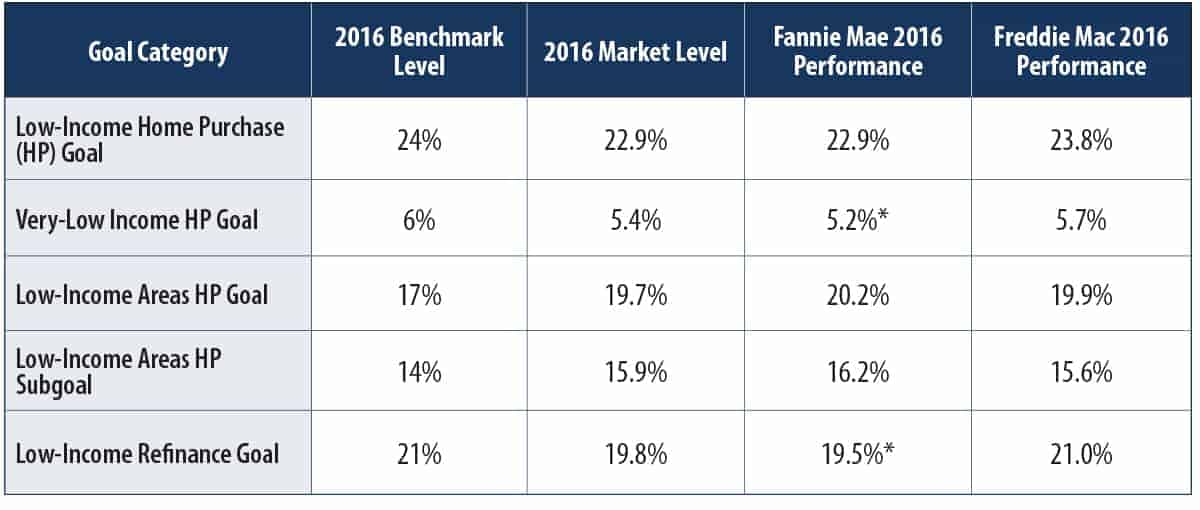

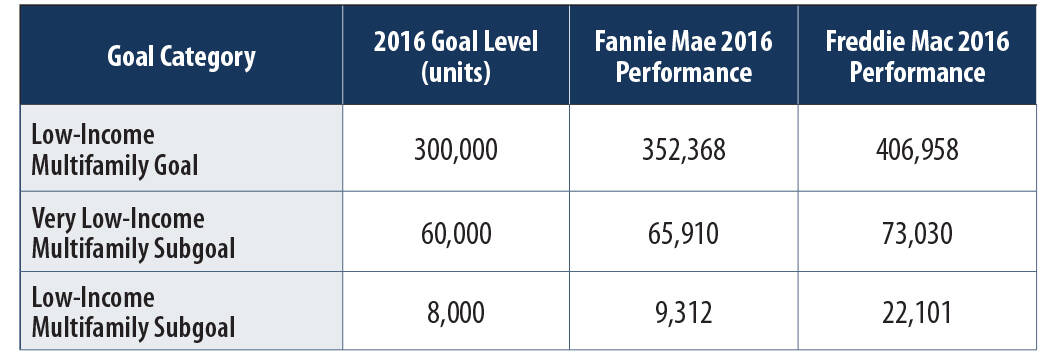

The Enterprises and Affordable Housing: The Enterprises play a critical role in housing finance, supporting over $5 trillion in mortgage loans and guarantees.[44] The Enterprises have an affirmative obligation in their charters to facilitate affordable housing that has been essential to ensuring access to affordable conventional mortgage credit for traditionally underserved borrowers and markets, including those in low-income, rural and minority communities.[45] The Enterprises’ affordable housing goals require that the Enterprises guarantee a set percentage of single-family and multifamily mortgages in low- and moderate-income communities every year. Right now, they are not being utilized to their full potential. Since 2010, one or both Enterprises have failed to purchase enough loans from lenders to meet one or more of their “benchmark” single-family housing goals on several occasions. The benchmark goal is set in advance by FHFA. On several occasions, they have lagged “market” performance on their goals. The market goal is the actual number of loans that were originated in the market and eligible for the Enterprises to purchase.[46] (see Figures 7 and 8).

2016 Single Family Housing Goals Performance

2016 Multifamily Housing Goals Performance

The Enterprises and Blame for the Financial Crisis: For years, opponents in Congress and some of the largest financial players in the private market, who view them as government-sponsored competitors, have blamed the Enterprises as well as their affordable housing goals for the financial crisis. Opponents have advocated for diminishing their role in the secondary mortgage market or scrapping them entirely, including their affordable housing goals.[47] The U.S. Financial Crisis Inquiry Report found, however, that although the Enterprises participated in the expansion of subprime and other risky mortgages, they followed rather than led Wall Street and other lenders – they were not the primary cause.[48] In the midst of an overall housing bubble and housing market meltdown, the loans purchased or guaranteed by the Enterprises generated substantial losses, but delinquency rates for the Enterprises’ loans were substantially lower than loans securitized by other financial firms.[49]

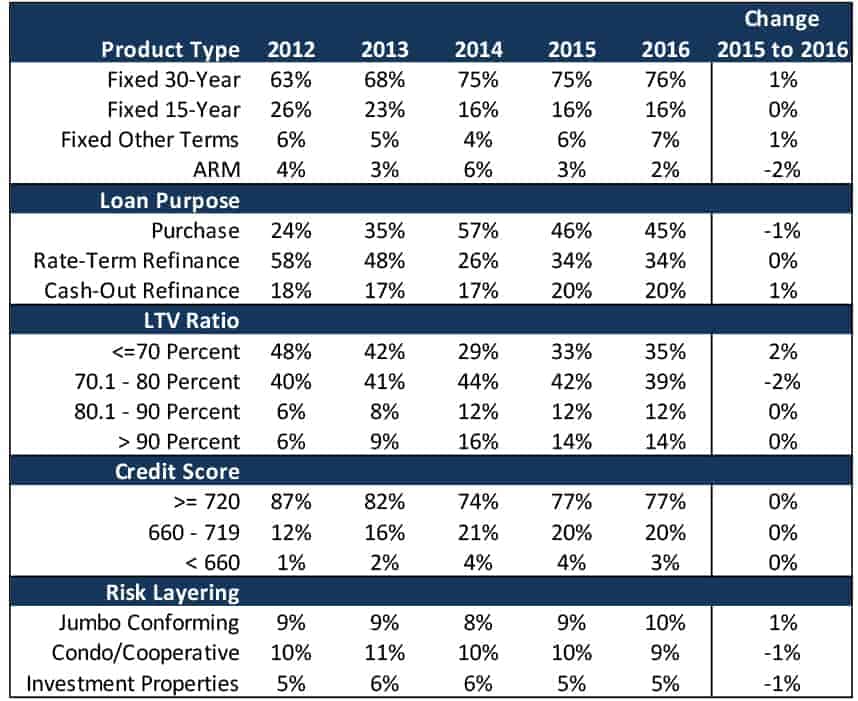

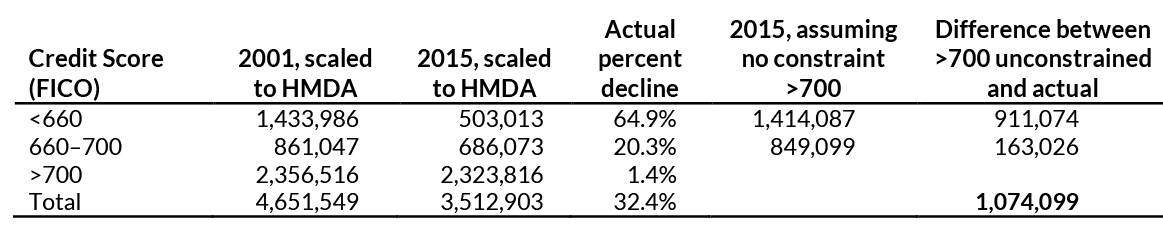

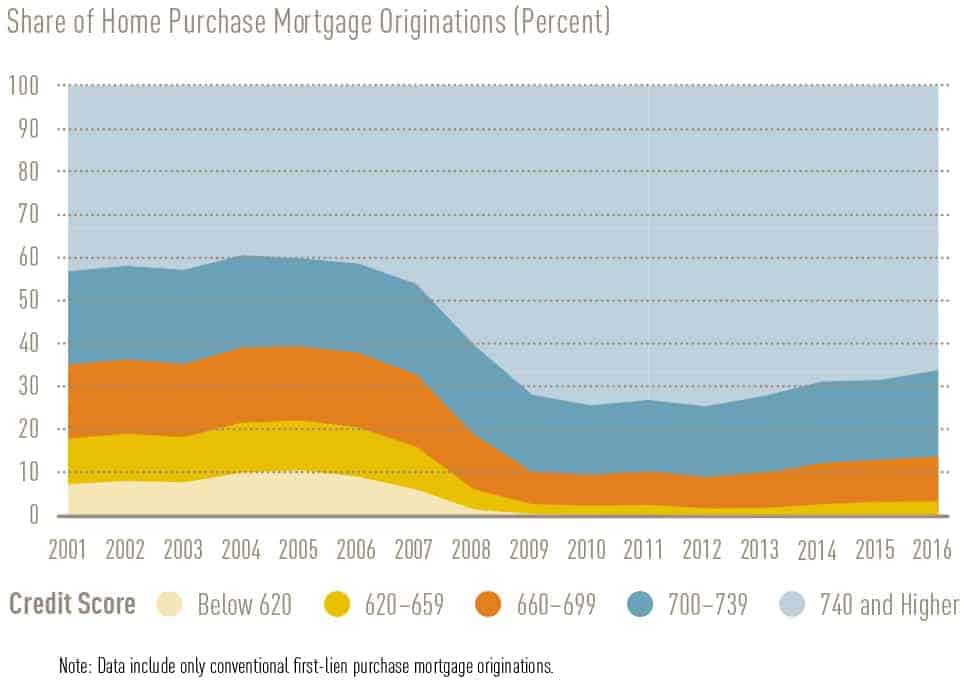

Tight Credit Access and the Enterprises in Conservatorship: In 2008, former FHFA Director Ed DeMarco placed the Enterprises in conservatorship, and both were put on a path to wind down their operations – their capital reserves, their loan portfolios and to shrink their role in holding credit risk in the secondary mortgage market. Since that time, both Enterprises have implemented risk-based pricing and increased their guarantee fees by 250 percent – fees that are passed on to homebuyers. Also, their credit score requirements have risen substantially – 77 percent of their mortgage guarantees are for borrowers with an average credit score at or above 720 (see Figure 9).[50]However, the average FICO score nationally is 700,[51] and a relatively small share of new mortgages are being originated to that share of creditworthy borrowers. Across the mortgage market, tight credit standards are estimated to have prevented 6.3 million mortgages between 2009 and 2015 if compared with standards during historical periods of safe lending (see Figures 10 and 11).[52] As a result, the wealth-building tool of homeownership is now out of reach for too many borrowers.

Acquisition Share by Risk Profile

Who Can Act:

The U.S. Congress, the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA), the U.S. Department of the Treasury

NCRC’s Position:

NCRC urges Congress to protect, defend and strengthen the affordable housing goals and affordable housing mission at the Enterprises. The Enterprises’ goals and mission are critical incentives in the law that facilitate conventional mortgage credit to underserved communities. The U.S. Financial Crisis Inquiry Report, research from the Federal Reserve Board of Governors, several Federal Reserve Banks and academics have all found that the housing goals should not be blamed for the financial crisis.[53]

Regardless of how Congress proposes to reform the secondary mortgage – with Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac or without – any new government-sponsored entities as well as any publicly financed securitization infrastructure must be subject to the affordable housing mandates and goals that the Enterprises have.

After nine years, it is time for FHFA and the U.S. Treasury to end the conservatorships of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. FHFA should also allow the Enterprises to increase their affordable loan product offerings, improve their pricing for low- and moderate-income borrowers, and improve marketing and outreach to African-American borrowers and other underserved communities and markets that are suffering specific setbacks in access to homeownership.

How Many Purchase Loans Are Missing Because of Credit Availability?

Tight Lending Standards Limit Mortgage Access for Households with Lower Credit Scores

ISSUE: Protect Funding of the National Housing Trust Fund and Capital Magnet Fund Even as the Enterprises Remain in Conservatorship

After the Enterprises were placed in conservatorship in 2008, former Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA) Director Edward DeMarco suspended the allocation of funds to the National Housing Trust Fund (NHTF) and the Capital Magnet Fund (CMF). On December 11, 2014, current FHFA Director Melvin L. Watt lifted the suspension, and directed the Enterprises to begin setting aside and allocating funds to the NHTF and the CMF.[54] In May 2016, HUD allocated $174 million through the NHTF[55] and in September the CDFI Fund awarded $91.5 million in CMF grants.[56]

The NHTF and the CMF were both created by the Housing and Economic Recovery Act of 2008 (HERA) to increase affordable housing opportunities and promote community development investments for underserved and distressed communities, consistent with safety and soundness.[57] The law requires the Enterprises to set aside 4.2 basis points for each dollar of unpaid principal balance on total new loan purchases, which are then allocated to the two funds.[58]

Following Director Watt’s decision to fund the NHTF and the CMF in 2014, critics in Congress attempted to block funding for the NHTF. Most recently, H.R. 4560 proposed suspending contributions by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to the NHTF. It should be noted that both FY2018 and FY2019 budgets from the Trump Administration proposed eliminating the NHTF and the CMF.

FHFA’s Duty to Serve Rule: Under the 2008 HERA law, the Enterprises also have a Duty to Serve three underserved markets: manufactured housing, affordable housing preservation and rural housing. Unlike the affordable housing goals, the law prohibits the Enterprises from setting loan purchase goals or designating a specific percentage of their business to comply with their Duty to Serve.[59] However, the rule requires them to purchase loans, develop loan products, conduct outreach and/or make investments in the three markets to receive Duty to Serve credit. In January 2018, both Enterprises began work under their Duty to Serve plans.

Who Can Act:

The U.S. Congress, the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA) and the U.S. Department of the Treasury

NCRC’s Position:

NCRC continues to oppose any efforts in Congress to defund the NHTF or the CMF through the annual appropriations process. Both Enterprises should also continue to set aside and allocate funds to the NHTF and CMF even as they remain in conservatorship.

FHFA’s Duty to Serve in the three underserved markets is an important complement to the Affordable Housing Goals. However, the affordable housing goals are a broader and stronger mandate that ensure low- and moderate-income borrowers and underserved communities have access to conventional mortgage credit. Both the affordable housing goals and the duty to serve must be defended and protected.

ISSUE: Rethink Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac’s Backing of Private Equity Investors in the Single Family Rental Market

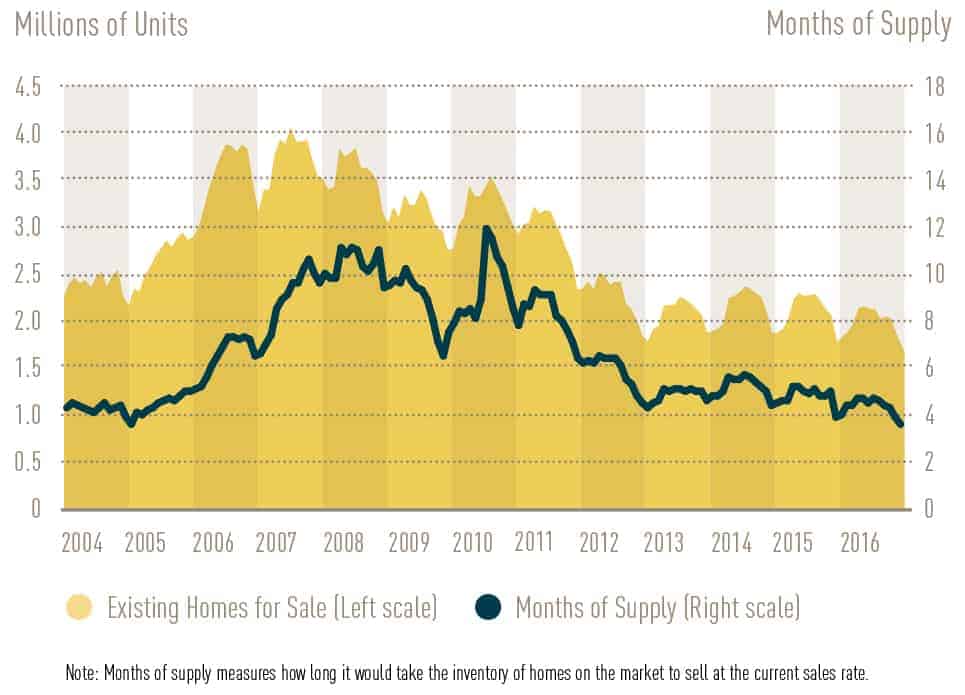

In 2017, Fannie Mae completed the first securitization of a single-family rental property by one of the Enterprises with a 10-year, $1 billion loan to Invitation Homes (IH), the country’s largest owner of single-family rental homes and a division of the private equity firm The Blackstone Group L.P.[60] This marks the first time that either Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac has guaranteed the debt of an institutional owner of single-family rental housing. The number of single-family rental units increased 35 percent from 2006 to 2016,[61] as Blackstone and other large institutional investors bought up hundreds of thousands of foreclosed single-family properties at rock-bottom prices and converted them to rentals.

U.S. homeownership has also fallen to a 50-year low since the housing crisis amid strict lending standards, mounting student debt, and would-be buyers’ savings and credit diminishing during the recession. (See Figure 12). Even as millennials and first-time homebuyers now enter the market, they are having difficulty finding affordable houses to buy.[62] IH homes are in the segment of single-family market suffering some of the tightest housing supply. The share of new homes 1,800 square feet or less (the typical size of entry-level homes) has fallen from 37 percent in 1999 to 21 percent in 2015.[63] IH single-family rentals average approximately 1,850 square feet and their portfolio of homes are in 13 desirable markets concentrated in the Western U.S and Florida.[64] IH and other institutional buyers of single-family homes compete with homebuyers seeking affordable homes to purchase.

Inventories of Homes for Sale Continue to Shrink…

Who Can Act:

The Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA), Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac

NCRC’s Position:

Fannie Mae should improve access to affordable homeownership in traditionally underserved communities instead of backing private-equity giants on Wall Street that are converting single family properties into rentals. Among other steps, the Enterprises should improve their pricing for low- and moderate-income borrowers, increase their affordable loan product offerings, and improve marketing and outreach to African-American borrowers and other underserved borrowers and markets that are suffering specific setbacks in access to homeownership. With regard to future deals, the Enterprises must attach affordability and tenant protections to these rentals.

ISSUE: Prioritize the Affordable Housing Needs of Rural Americans

Nearly 74 million Americans, including more than 15 million people of color, live in rural America where getting access to credit and capital for affordable housing is especially difficult.[65] The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) Section 502 Single Family Housing Direct Loan Program, the Section 515 Rural Rental Housing Direct Loan Program, and the Section 521 Rural Rental Assistance Program are all critical to homeownership and rental housing in rural communities.

The Section 502 Direct Loan Program offers mortgages for low-income homebuyers in rural areas.[66] At least 40 percent of the funds appropriated each year must be used to assist families with incomes less than 50 percent of area median income (AMI).[67] In the past 60 years, Section 502 Direct Loans have helped more than 2.1 million rural families buy homes and build their wealth by more than $40 billion.[68] The Section 515 Program has financed more than 550,000 decent, safe, sanitary and affordable homes, often the only such housing in rural communities.[69] USDA’s Section 521 Rental Assistance (RA) program helps tenants whose incomes are so low they cannot afford the rent in certain USDA-financed properties.[70]

Who Can Act:

The U.S. Congress House and Senate Budget and Appropriations Committees, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA)

NCRC’s Position:

Congress and the Trump Administration should prioritize and support capacity building for Section 502 Direct Loans so that more rural Americans can access and use the program. Although the program has recently been automated, it still takes far too long to process loan applications.

The House and Senate Appropriations Committees should also maintain funding for all USDA rural housing programs, including Section 502, 514, 515, 516 and 521. Congressional appropriators should also provide enough funding to renew all Section 521 rental assistance contracts, oppose implementing minimum rents in Section 521-assisted units or other USDA rentals, and work with USDA Rural Development to find positive ways to reduce Section 521 costs through energy efficiency measures, refinancing USDA mortgages, and reducing administrative costs.

FHFA’s Duty to Serve Rule: The Underserved Market Plans being executed by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac as part of their Duty to Serve obligations for the manufactured housing market should promote strong homeowner and tenant protections in the market, including long-term leasing, investments in mission-owned communities, safe and sound financing as part of the chattel loan pilot program, and no restrictions on the right to sell.

Invest Forward

ISSUE: Ensure that Innovative FinTech Companies Have Requirements Around Consumer Protections, Transparency and Affirmative Obligations That Mirror Those For Banks

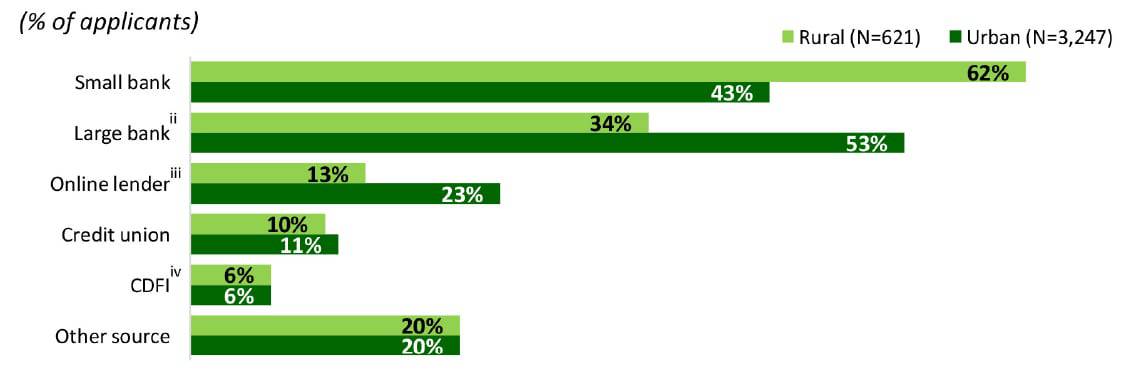

Financial technology companies (FinTechs) are non-depository institutions such as online marketplace lenders, payment processors and others nonbank providers that are growing at a rapid pace. Thirteen of the online lending sector’s largest firms made $15.91 billion in U.S. loans in 2014, up 700 percent from 2010, and in the first six months of 2015 the same firms extended $12.47 billion in credit nationwide.[71] Online lending has been growing as a credit source for small and microbusinesses (see Figure 13).

The growth of the industry has ignited the interest of several federal regulators. In December 2016, the OCC announced an intention to explore a national bank charter for FinTech companies and sought public comments. Among other issues, the OCC sought feedback on issues around financial inclusion for underserved borrowers and how obligations similar to those under CRA, that apply to the nation’s traditional banks, might be extended to FinTech and online marketplace lenders.[72]

Online marketplace lending involves the facilitation of loan originations outside of the traditional consumer banking system by collecting information from a borrower and underwriting a loan with a lender entirely over an internet platform, a process designed to be efficient and cost-effective for lenders and user-friendly for borrowers. Lending platforms typically issue loans in amounts ranging from $1,000 to $35,000 with maturities of three to five years, and may include fixed or variable interest rates, origination fees and/or other charges that may not all be apparent to the borrowers.[73]

While online lending platforms have the potential to expand access to credit for the underserved, several concerns have arisen around FinTech companies[74] and the prospects of the OCC extending a national bank charter to them, including:

- Whether FinTechs will be subject to requirements similar to those that banks must meet under CRA;

- Whether a national bank charter for FinTech companies will undermine or preempt stronger consumer protections in state law as well as state interest rate caps;

- Whether “rent-a-charter” schemes, in which FinTech companies lend and operate in partnership with a nationally chartered or state-chartered bank, allow FinTechs to get around state interest caps and other consumer protections;

- While innovative data-driven underwriting methods may expedite credit assessments for borrowers and reduce costs for lenders, they also carry the risk of disparate impact in credit outcomes and could hide the potential for fair lending violations;

- Many consumer protections that apply to consumers when borrowing through online lending platforms do not extend to small business borrowers;

- The lack of more transparent pricing terms for borrowers and standardized loan-level data for investors; and

- FinTechs remain untested through a complete credit cycle and higher charge-off and delinquency rates for recent vintages of consumer loans may be an early indication of larger risks should credit and economic conditions deteriorate.

Who Can Act:

The U.S. Congress, Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (the OCC), the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), the Federal Reserve System, the U.S. Department of the Treasury, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), the Federal Trade Commission, and others.

NCRC’s Position:

If the OCC develops a national bank charter for FinTech companies, the OCC must extend to them similar requirements around CRA that banks comply with today. It should not preempt stronger state law protections and interest rate caps. It must also establish stringent safety and soundness, and rigorous supervision and examination of compliance with fair lending and consumer protection laws for newly chartered institutions.

A national bank charter is a tremendous benefit for FinTechs since, among numerous other features, it allows them to lend nationwide without having to seek permission state by state. It has the potential to benefit consumers and communities only if it is accompanied by rigorous CRA-like obligations in addition to rigorous supervision and oversight. Safety and soundness reviews must also be stringent.

Application Rates By Credit Source

ISSUE: Improve Funding for HUD-Approved Housing Counseling Agencies to Support a Pathway to Homeownership

Pre-purchase housing counselors work to prepare families for responsible homeownership, and research consistently demonstrates that pre-purchase counseling works. Analysis by the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia in 2014 found that a two-hour pre-purchase homeownership workshop and one-on-one pre-purchase counseling improved the participants’ financial creditworthiness as they prepared to qualify for a home mortgage.[75]Homeowners and prospective homeowners who receive counseling have higher credit scores, less overall debt, and lower delinquency rates. A 2013 study that looked at 75,000 mortgages found that borrowers who received pre-purchase counseling and education were one-third less likely to become seriously delinquent than similar borrowers who did not receive pre-purchase counseling and education.[76] A 2017 report on housing counseling prepared by HUD found that pre-purchase education and housing counseling appeared to be associated with factors related to sustainable homeownership. [77]

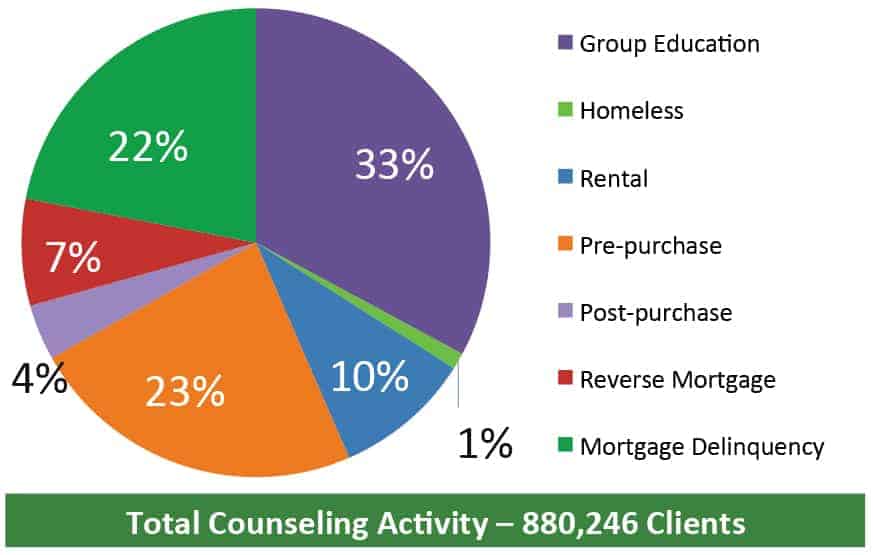

Whether preparing first-time homebuyers for the financial commitment of homeownership, helping homeowners to resolve mortgage delinquencies and avoid foreclosure, helping renters find affordable rental options, or working with older adults to help them stay in their homes, the services HUD-approved housing counseling agencies provide are essential to meeting the housing needs of families in communities all around the country. The federal funding provided for housing counseling is critical to ensuring that HUD-approved housing counseling agencies can continue to serve families in need. A recent report from the Urban Institute prepared for NeighborWorks America found that counseled clients were 2.83 times more likely to receive a loan modification and were 70 percent less likely to re-default on a modified loan than were similar borrowers who were not counseled. Counseled clients were given modifications that saved them $732 per year compared with modifications given to non-counseled borrowers.[78] It should be noted that with HUD focusing more on group education and financial capability and coaching than in previous years (Figure 14), and with the NFMC program winding down, there is a growing need for housing counselors to collaborate with banks for program funding.

Improve Funding for HUD-Approved Housing Counseling Agencies to Support a Pathway to Homeownership

Examples of how government funding can leverage the private market can be found in the partnerships formed between housing counseling programs and the private sector. Housing counseling services are vital resources in many underserved, but growing, communities across the country and a number of mortgage servicers have started to take notice. Lenders have learned they can reduce their costs by partnering with housing counseling agencies to help potential homeowners prepare their loan application documentation, which in turn increases the number of closed loans processed. Housing counseling agencies have also assisted mortgage servicers in reaching out to struggling homeowners to both prepare documents for loan modifications or to help transition homeowners into a more affordable rental option. It is examples such as these that show the importance of housing counseling in a still-recovering housing market.

Who Can Act:

The U.S. Congress, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), Financial Institutions

NCRC’s Position:

NCRC urges the House of Representatives and Senate Appropriations Committees to include $60 million for the HUD Housing Counseling Assistance (HCA) program. The HCA program funds critical services for homeowners and seniors at risk of foreclosure.

Recognizing the effectiveness and the need for housing counseling services, NCRC also urges financial institutions to partner with housing counseling agencies to make:

- Consistent referrals for potential homeowners to receive pre-purchase counseling.

- Referrals for denied applicants to receive products and services from housing counseling agencies.

- Establish fee for service agreements with local housing counseling agencies to serve homeowners who are delinquent on their mortgages.

Invest Fair

ISSUE: Oppose Efforts to Undermine Fair Housing Enforcement, Including HUD’s Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing (AFFH) and Disparate Impact Rules

Earlier this year, HUD notified its program participants (states, counties, municipalities and public housing agencies) that the agency has delayed the requirement that they submit an Assessments of Fair Housing (AFH) until after October 31, 2020. HUD also notified participants that they will not be required to submit an AFH using the current version of the Assessment tool. The Assessment Tool is a critical piece of the Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing (AFFH) rule finalized in 2015. With this delay, HUD has effectively suspended key pieces of the AFFH final rule, however, the agency has said that local governments must continue to comply with existing obligations to affirmatively further fair housing, and program participants that have already submitted an AFH that has been accepted by the agency must continue to execute the goals of that AFH.

In 2015, HUD released its Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing (AFFH) rule, which implements two of the primary goals in the Fair Housing Act of 1968. The first goal is to end housing discrimination and promote diverse, inclusive communities. A second, less well-known goal is meant to affirmatively further fair housing – to actively dismantle segregation and foster integration in its place. Until 2015, the second goal had been largely forgotten, neglected and unenforced for decades.

The AFFH rule is a locally driven evaluation and goal-setting process that requires cities and towns across America to analyze and publicly report racial bias in their housing patterns every three to five years, and to set goals to reduce segregation. The rule is a tool provided to the local communities for them to implement in the best way possible for their communities. HUD’s strong AFFH rule provides clarity and teeth to the law’s long-standing obligations while also providing a number of tools communities can leverage to implement strong local fair housing programs.[79]

Disparate Impact: In 2013, HUD also finalized a Disparate Effects rule – a uniform standard for analyzing evidence of disparate impact in cases brought under the Fair Housing Act.[80] In 2015, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the disparate impact doctrine under the Fair Housing Act in Texas Department of Housing and Community Affairs vs. Inclusive Communities Project. [81] The disparate impact doctrine bars policies that have a discriminatory impact even if there is no intention to discriminate. This tool is very important to fair housing and fair lending advocates combating modern-day redlining where an intention to discriminate can be nearly impossible to prove.

Congressional opponents of HUD’s AFFH rule and disparate impact rules have repeatedly sought to undermine them through “riders” or amendments in the annual appropriations process by barring HUD from spending any money to enforce them. More broadly, Congress has sought to undermine fair housing enforcement by not funding or underfunding it.

Who Can Act:

The U.S. Congress, the House of Representatives and Senate Appropriations and Budget Committees, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD)

NCRC’s Position:

NCRC urges Congress to oppose all amendments in the FY 2019 budget and appropriations process to defund HUD’s AFFH or disparate impact rules, and also to defund or underfund the Fair Housing Initiatives Program (FHIP) and broader fair housing enforcement.

NCRC urges HUD to continue implementing the AFFH final rule, including the AFFH data and mapping tool. This tool is useful not only for developing an AFH plan, but is vital for researchers and advocates to pinpoint areas of potential segregation and those in need of community reinvestment.

ISSUE: Protect the CFPB’s Mission and Structure to Ensure a Fair and Transparent Financial System

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) has been under fire from Wall Street and some members of Congress since its very inception. The agency was created by the Dodd-Frank Act in 2010 and aims to ensure that financial markets work for consumers, responsible providers, and the economy as a whole. It protects consumers from unfair, deceptive, or abusive practices and takes action against companies that break the law. The CFPB’s jurisdiction includes traditional lenders such as banks and credit unions, but extends also to securities firms, payday lenders, mortgage servicing operations, foreclosure relief services, debt collectors, and other financial companies operating in the United States.[82] The CFPB has handled 1.2 million complaints since 2011 with the top two products being debt collection and mortgage.[83] (Figure 15)

In November of 2017, Richard Cordray, who had been the Director of the CFPB since its inception, resigned.[84] President Trump, in turn, appointed current OMB budget director, Mick Mulvaney, a frequent critic of the agency, to run the agency on an interim basis.

CFPB’s Funding and Structure: While no other bank regulator is subject to the annual appropriations process in Congress, opponents of the CFPB have suggested making the CFPB subject to annual appropriations, thereby tying its funding to the political winds of Congress instead of letting it operate as the independent agency it was designed to be. Along with the CFPB, the Federal Reserve System, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) are funded independent of Congress’ annual appropriations process through bank fees, in order to insulate them from political pressure and manipulation by big-bank political donors.

Another proposal would replace the single, accountable director with a board of directors or make it a commission. There is nothing unprecedented about the current structure of the CFPB. In fact, the much larger OCC has been led this way since it was established in 1863.[85] In addition to the OCC, single directors head both the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA) and the U.S. Social Security Administration.

Other congressional proposals designed to undermine the CFPB’s effectiveness include efforts to strip the agency of supervisory authority, remove its enforcement authority over unfair and deceptive acts and practices, and limit its rulemaking power, among others.

There are multiple mechanisms already in existence to ensure the CFPB’s accountability and transparency. The CFPB must report twice a year to Congress[86]– an obligation shared only with the Federal Reserve System. The Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC) has the authority to veto the CFPB’s (and no other financial regulator’s) rules.[87] The CFPB is also accountable to the independent Inspector General for the Federal Reserve System’s Board of Governors and to the Government Accountability Office (GAO). The GAO, both on its own behalf and in response to congressional requests, has conducted oversight and audits of the CFPB on repeated occasions. Also, CFPB rules and enforcement actions can be and have been challenged in federal court.

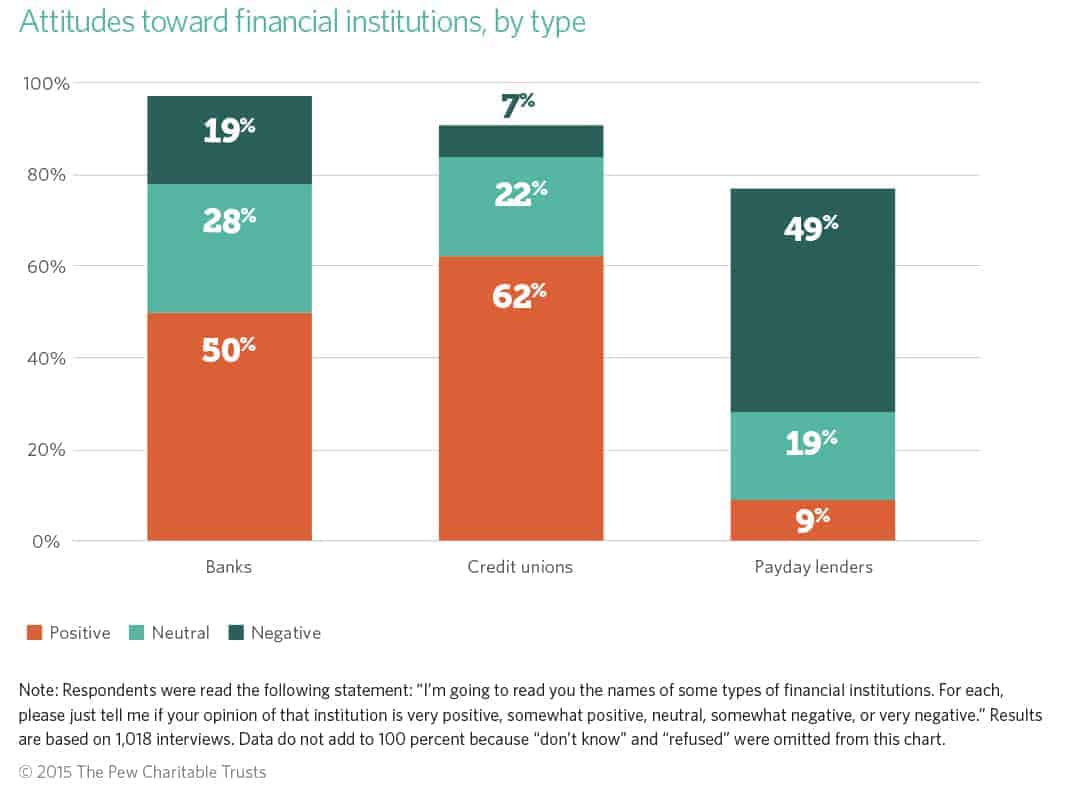

CFPB’s Payday Lending Rule: Recently, CFPB Director Mick Mulvaney announced that intend to engage in a rulemaking process to reconsider their own Payday Rule.[88] The agency’s payday lending rule is critical to addressing the rise in predatory lending seen following the financial crisis. This announcement by the CFPB followed an effort by the House of Representatives to roll back the CFPB rule via the Congressional Review Act, which is a law that gives Congress 60 session days to nullify a regulation via a majority vote.[89]

Only 1 in 10 Americans View Payday Lenders Positively

Who Can Act:

The U.S. Congress, the U.S. House of Representatives and U.S. Senate Appropriations and Budget Committees

NCRC’s Position:

Congress should not attempt to weaken the power of this critical agency that has already done a great deal to protect consumers and create a safer financial system free from fraud and abuse; nor should it consider any legislation to replace the CFPB. NCRC also opposes efforts from within the CFPB to change its mission from consumer protection to regulatory reform.

NCRC opposes H.R. 10, The Financial CHOICE Act, sponsored by Representative Jeb Hensarling (R-TX- 4), Chairman of the House Financial Services Committee. The Financial CHOICE Act proposes a rollback of numerous critical provisions of the Dodd-Frank Act, including those related to the CPFB. Also, NCRC opposes various standalone bills seeking to undermine the agency, including: S. 370 (Sen. Ted Cruz (R-TX)); S. 387 (Sen. David Purdue (R-GA)); H.R. 1031 (Rep. John Ratcliffe (R-TX-4); and H.R. 1018 (Rep. Scott DesJarlais (R-TN-4).

ISSUE: Protect Section 1071 of the Dodd-Frank Act to Ensure Better Access to Credit for Small Businesses

Section 1071 of the Dodd-Frank Act requires that the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) centralize the collection of small business lending data and to make that data public. It also requires new data including the race and gender of the small business owner to be reported.

The purpose of this section is to “facilitate the enforcement of fair lending laws and enable communities, governmental entities, and creditors to identify business and community development needs and opportunities of women-owned, minority-owned, and small businesses.” Currently, the collection of small business lending data is spread across a number of federal agencies, is not comprehensive, and is not readily available to the public.

Small, women-owned, and minority-owned businesses (SBEs, WBEs and MBEs) drive economic and job growth. Small businesses accounted for approximately 60 percent of net new jobs created from mid-2009 through the third quarter of 2016.[90] Women, African-American, and Hispanic entrepreneurs represent a larger share of small businesses than ever. Between 2007 and 2016, the number of women-owned businesses increased by 45 percent, compared to just a 9 percent increase among all businesses.[91] Nonetheless, the country continues to rebound from a 40-year decline in startup activity.[92]

Despite their significant role, small, women-owned, and minority-owned businesses struggle the most with access to safe and sustainable credit. Bank balance sheets showed a 20 percent decline in small business lending by 2014, while loans to larger businesses had risen by about four percent over the same period.[93] Also, small businesses, women-owned, and minority-owned businesses face lower approval rates on loans than male-owned and non-minority-owned businesses. For example, available research on minority business lending generally indicates that African-American business owners are denied loans more often or pay significantly higher interest rates than white-owned businesses with similar risk characteristics.[94]

Despite disparities in lending, a 2008 GAO report found that the lack of data frustrates regulators’ ability to address it. Better data on lending markets improves access to credit.

Who Can Act:

The U.S. Congress, The CFPB

NCRC’s Position:

NCRC opposes congressional attempts to repeal Section 1071, including H.R. 10, the Financial CHOICE Act of 2017, sponsored by Representative Jeb Hensarling (R-TX-4),[95] Chairman of the House Financial Services Committee, and any similar proposal by Senator Mike Crapo (R-ID), Chairman of the Senate Committee on Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs or in any appropriations riders. The Financial CHOICE Act proposes a rollback of numerous critical provisions of the Dodd-Frank Act, including a repeal of Section 1071. NCRC opposes any repeal of Section 1071. Better small business lending data must be defended.

Additionally, in accordance with Section 1071, the CFPB completed its Request for Information regarding small business data collection. NCRC, along with several other advocates and community development lenders, urged strong rulemaking from the CFPB and opposed any efforts to diminish and/or eliminate Section 1071.

SBE, MBE and WBE Procurement: Additionally, to ensure that small, women-owned, and minority-owned businesses can continue to grow, the federal government should increase their contracting and procurement goal with small businesses from 23 percent to 25 percent and actually adhere to that standard. For years, the government has failed to meet its goals of awarding a mere 23 percent of federal contracts to these businesses, depriving them of at least $25.7 billion. In addition, many federal programs aimed at providing technical assistance have arbitrary and unnecessary limiting constraints.

ISSUE: Improve Public Data About the Mortgage Market and Loan Products

Prior to the 2007-2009 financial crisis, it became evident to the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) and others that the current data collected under the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA) was insufficient for use in monitoring predatory lending practices. Primarily, a lack of information on loan terms and conditions, as well as characteristics of borrowers, left regulators and advocates without the tools needed to discourage lenders from offering high-cost mortgage loans with abusive terms and conditions to vulnerable consumers.[96] As a result, the Dodd-Frank Act of 2010 made a number of improvements to mortgage market data collection under HMDA.

In October 2015, the CFPB issued its final rule improving the quality and the type of HMDA data it collects. This new information includes the property value, debt-to-income ratios, pricing information for all loans, loan terms such as the presence of prepayment penalties, and additional borrower characteristics such as age, to help identify emerging risks and abusive lending practices.[97] This new data will also enhance fair lending reviews because agencies will have more data with which to test whether similarly situated applicants that differ only by race, age, or gender are receiving loans with similar terms and conditions.

As part of the rule, the CFPB adopted a standard that applies the new reporting requirements to institutions that made 25 closed-end mortgage loans or 100 open-end/home equity lines of credit (HELOCs). Importantly, in response to concerns raised by lenders and by some in Congress, the CFPB has already temporarily raised the reporting threshold for HELOCs to 500 through 2019, in order to further review the impact of the rule and what the permanent HELOC threshold should be.[98]

Opponents of the new and better HMDA data are seeking to repeal the Dodd-Frank authority for expanded HMDA reporting, to exempt more financial institutions from having to report at all under the law, and to delay or completely suspend the public release of the new HMDA data that the CFPB is now collecting for further study on protecting borrower privacy.[99]

Making Better HMDA Data Public: The effectiveness of the new rule will be contingent on how the CFPB chooses to disclose data to the public. HMDA data is a powerful tool in fighting for a more just economy. In 2017, 6,762 financial institutions reported information about approximately 16.3 million mortgage applications, pre-approvals, and loans.[100]

In 2017, the CFPB issued its determination of which of the new data should be publicly disclosed, after carefully considering a balancing test to determine whether and how HMDA data should be modified prior to public release in order to protect privacy while also fulfilling the public disclosure requirements of the statute.[101] However, the final determination called for some key data points to be withheld from the public. Additionally, some in Congress have sought to further limit public access to this critical data, seeking to frustrate the main purpose of the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act in identifying whether lending institutions are serving credit needs in a responsible and non-discriminatory manner.[102]

Who Can Act:

The U.S. Congress, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB)

NCRC’s Position:

NCRC opposes congressional efforts to repeal, delay, or block the release of the new and better HMDA data or to exempt more financial institutions from having to report under the law. Specifically, NCRC opposes H.R. 10, theFinancial CHOICE Act, S.2133, the CLEARR Act, S.1310/ HR.2954, the Home Mortgage Disclosure Adjustment Act, and S. 2155, Economic Growth, Regulatory Relief, and Consumer Protection Act, all of these bills would exempt the vast majority of the nation’s banks and credit unions from having to update reporting about their mortgage lending under HMDA. H.R. 4648, Home Mortgage Reporting Relief Act of 2017 exempts depository institutions from reporting any of the new HMDA data.

The CFPB has issued a strong final HMDA rule, which could do much to shed light on lending activities. HMDA is a public disclosure statute, and the CFPB should lean towards full public disclosure while taking steps to ensure that the privacy interests of borrowers are protected. NCRC urges the CFPB to make public some of the data, such as an indication of applicant creditworthiness, it decided to exclude from public disclosures.

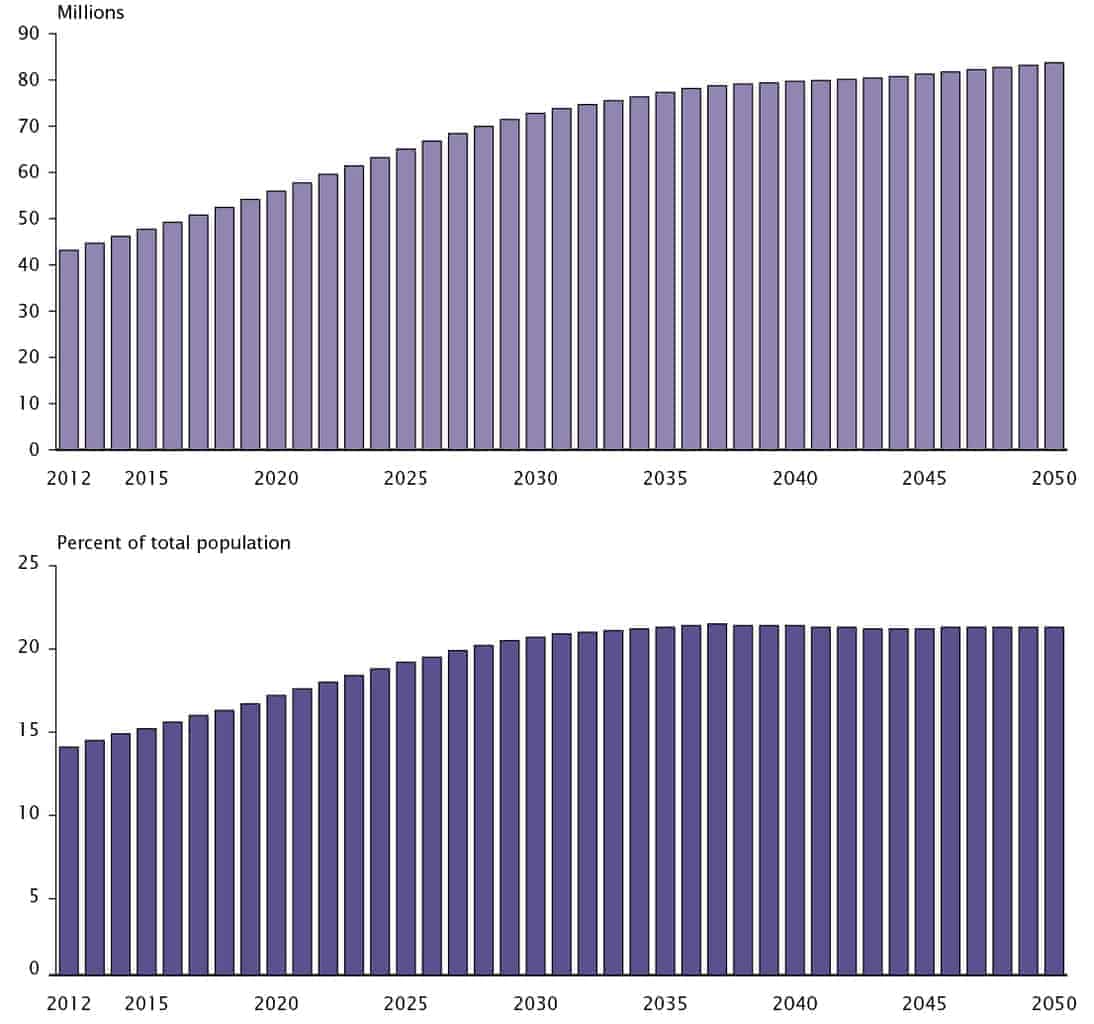

ISSUE: Provide Incentives for Financial Institutions to Adopt Age-Friendly Banking

With an expected 72 million older adults living in the United States by 2030,[103] the “Silver Tsunami” of American seniors will need age-sensitive financial products and services in order to continue living healthy and independent lives.

Who Can Act:

The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), the Federal Reserve System, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), the U.S. Congress in its oversight role

Population Aged 65 and Over for the United States: 2012 to 2050

NCRC’s Position:

The financial industry must do more to ensure that they are equipped to meet the unique banking needs of older adults. In its report, Staying at Home: The Role of Financial Services in Promoting Aging in Community, NCRC defines six core Age-Friendly Banking principles to effectively serve the older adult population:[104]

- Make financial management affordable;

- Ensure older adults’ access to critical income supports;

- Implement financial abuse protections and training;

- Facilitate aging in the community;

- Support aging services and advocacy; and

- Increase the accessibility of locations and services.

Invest Period

ISSUE: Continue to Invest in the Critical Infrastructure of the Country

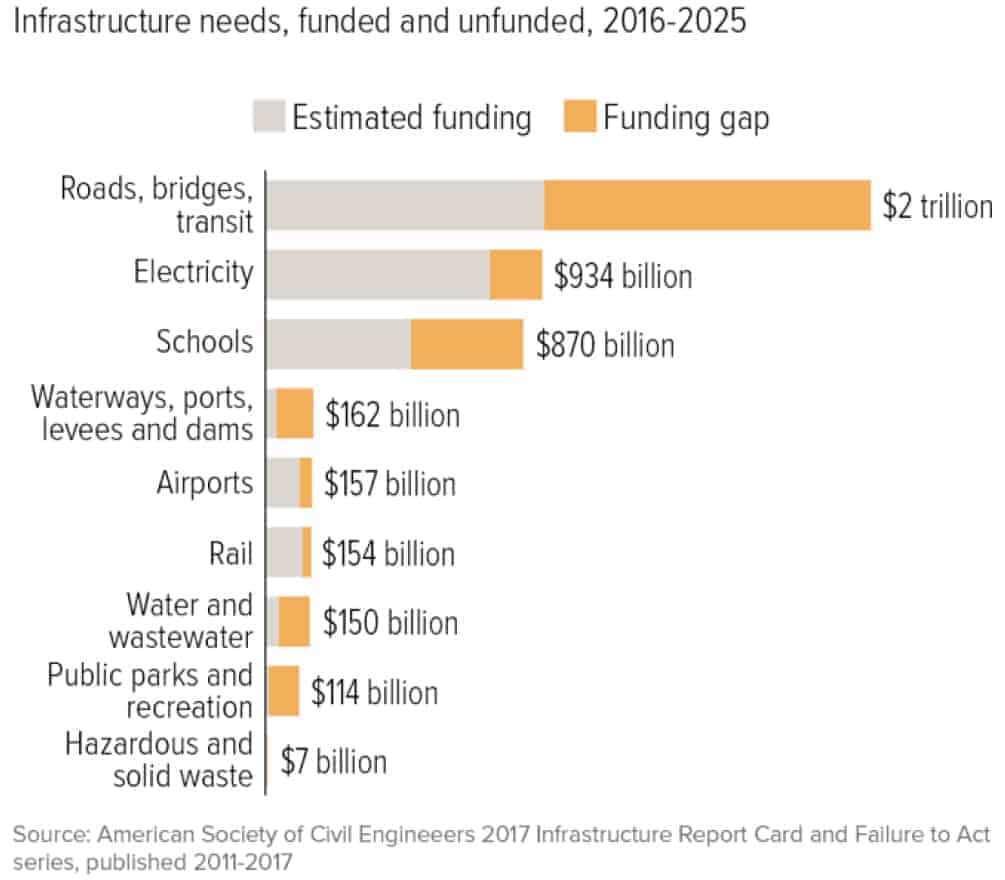

At this year’s State of the Union, President Trump called on Congress to produce a bill that generates at least $1.5 trillion for the new infrastructure investment the country needs. He noted that every federal dollar “should be leveraged by partnering with State and local governments and, where appropriate, tapping into private sector investment — to permanently fix the infrastructure deficit.”[105] There is bipartisan agreement among Democrats and Republicans at the federal, state and local level that there must be a major commitment to the nation’s infrastructure. From public housing to public schools, from roads, bridges and transit to waterways, the energy smart grid to airports and other public infrastructure, lawmakers must prioritize investments in the nation’s infrastructure and the need is great (see Figure 18). Communities around the country need strong infrastructure to grow, thrive and prosper.

Once the infrastructure plan was finally released in February, notably absent was any mention of affordable housing. A recent report from the Campaign for Housing and Community Development Funding (CHCDF) found that affordable rental homes located in areas with access to transportation, healthcare, good schools, and jobs with a decent salary help American families climb the economic ladder, which in turn leads to increased community development.[106] Local economies are increased when public and private resources are leveraged to invest in affordable housing infrastructure, which generates income and supports both job creation and retention.

Public Infrastructure Has Been Neglected

Who Can Act:

The U.S. Congress, state and local governments

NCRC’s Position:

NCRC supports a strong bipartisan plan that invests in and rebuilds the nation’s crumbling infrastructure and that are built with community benefits agreements.

ISSUE: Any Increases in Defense Spending Should Not Come at the Expense of Vital Domestic Programs.

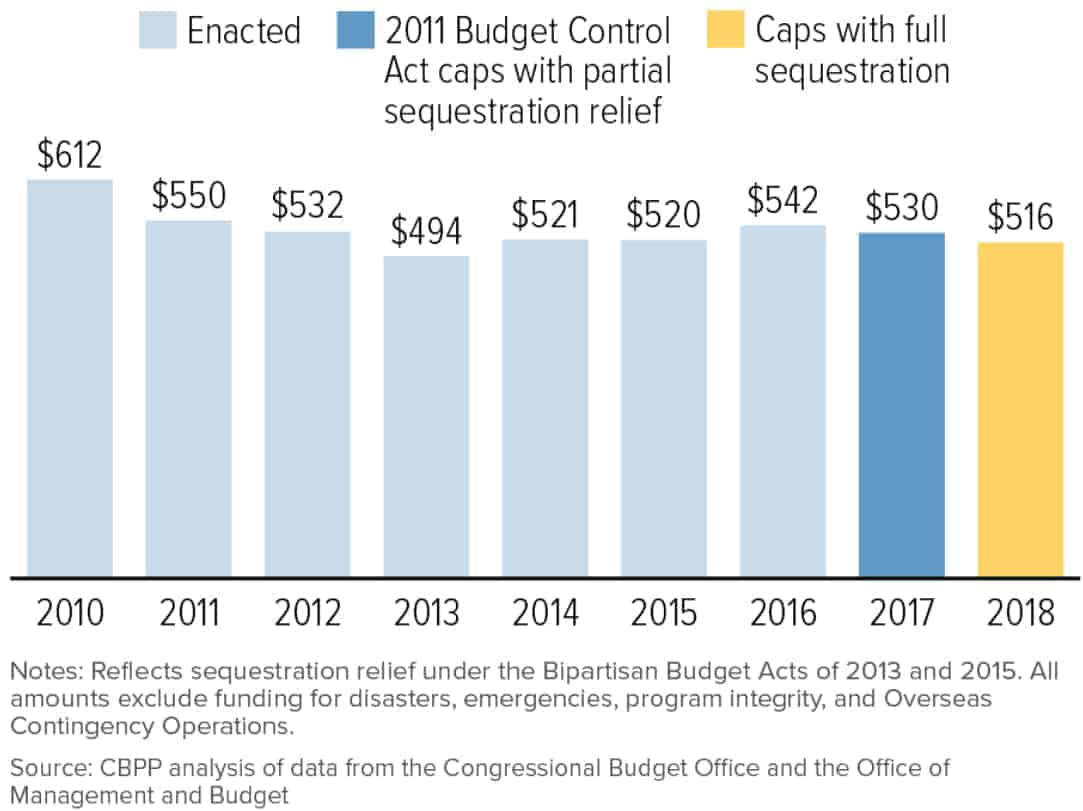

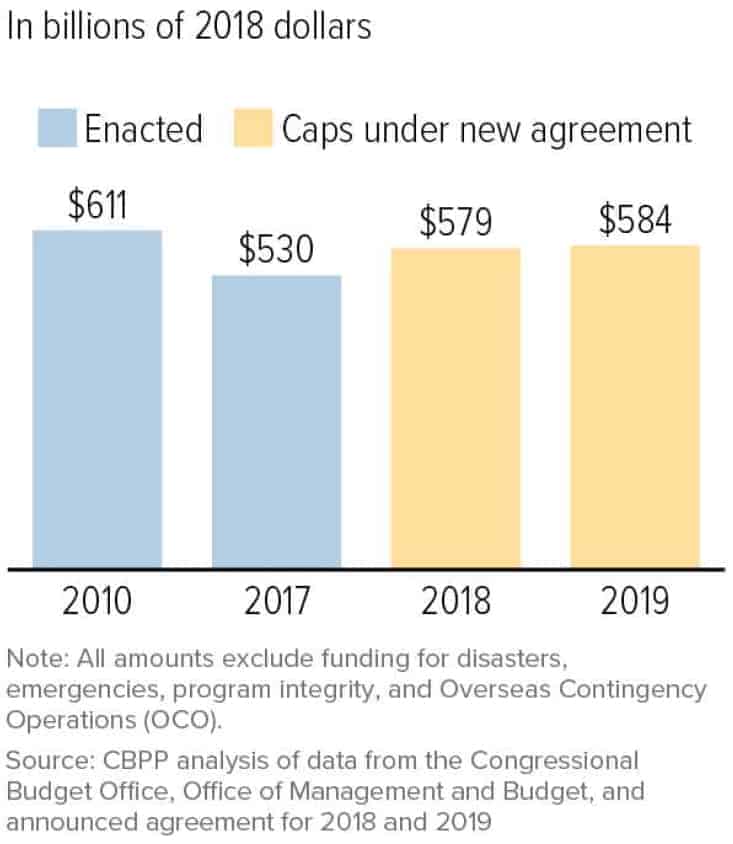

The non-defense discretionary (NDD) portion of the budget includes funding for both domestic and international programs falling outside of the national defense programs Congress annually appropriates. NDD includes critical funding for many of the nation’s housing, transportation and economic development, education and training, social safety net and economic security programs, health care and health research, law enforcement and other programs. NDD programs have been subject to repeated cuts through both spending caps and automatic spending cuts established by the 2011 Budget Control Act. Fortunately in February 2018, House and Senate leaders reached an agreement that would raise the limits on both defense and NDD spending. Even with the agreement’s substantial boost to overall NDD funding, spending will remain below its level of eight years ago in inflation-adjusted terms — a sign of how much this part of the budget has been squeezed in recent years (Figure 19).[107]

The most recent FY2018 budget agreement passed in February raised the spending limits for both NDD and defense spending for 2018 and 2019 set by Congress in the 2011 Budget Control Act. This increase in funding still falls short of the levels needed to return NDD funding to where it was eight years ago.[108] The new cap on NDD appropriations in 2018 would still be 5.3 percent below the comparable 2010 level; if adjusted for population growth as well as inflation, it would be 11.0 percent below the 2010 level (see Figure 20).[109]

Non-Defense Appropriations Well Below 2010 Level

Non-Defense Discretionary Funding Increases Under Bipartisan Deal Yet Remains Below 2010 Level

NDD or domestic programs cost far less than most would think. Historically, NDD has represented less than one-fifth of our nation’s entire budget, and less than 4 percent of the economy (gross domestic product or GDP). Cuts to NDD are seen by many as a way to cut the deficit, but most agree that NDD does not actually contribute to our nation’s long-term debt.[110] These NDD cuts have consequences and hamper our nation’s economic recovery, business growth and development, infrastructure and housing, and veterans’ services.

Who Can Act:

The U.S. Congress, Trump Administration

NCRC Position:

NCRC urges lawmakers to continue the precedent set in the Budget Control Act and in successive bipartisan budget agreements in 2013, 2015 and 2018 that ensure parity in defense and nondefense funding. For every dollar of sequestration relief granted to defense, NDD programs need to receive at least one dollar of relief.

NCRC also calls on Congress to lift the spending caps with parity for defense and non-defense programs and to ensure the highest level of funding possible for affordable housing and other critical domestic programs.

[1] The State of the nation’s housing 2017. (Cambridge, MA: Joint Center for Housing Studies, Harvard University, 1988.) Retrieved from http://www.jchs.harvard.edu/sites/jchs.harvard.edu/files/harvard_jchs_state_of_the_nations_housing_2017.pdf.

[2] 2017 Kauffman Index of Startup Activity (Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation). Retrieved from www.KauffmanIndex.org.

[3] Adam J. Levitin and Janneke H. Ratcliffe, Rethinking Duties to Serve in Housing Finance. (Cambridge, MA: Joint Center for Housing Studies, Harvard University, October 2013.)

[4] The Community Reinvestment Act, 12 U.S.C. §2901, et al.

[5] Jill Littrell and Fred Brooks, In Defense of the Community Reinvestment Act. (Atlanta: Georgia State University, 2010.)

[6] 135 Cong. Rec. S6681-S6775 (daily ed. June 15, 1989) (statement of U.S. Representative Bob Walker).

[7] Enforcement Actions [Redlining]. Retrieved from https://www.consumerfinance.gov/policy-compliance/enforcement/actions/?page=2#o-filterable-list-controls.

[8] NCRC calculations using FFIEC tables on small business and community development lending, see national aggregate reports from 1996 through 2016 available via https://www.ffiec.gov/craadweb/national.aspx.

[9] Eric Rosengren, Janet Yellen, John Olson, Prabal Chakrabarti, Ren S. Essene, and Randall Kroszner, Revisiting the CRA: Perspectives on the Future of the Community Reinvestment Act (Boston and San Francisco: Federal Reserve Banks of Boston and San Francisco, 2009). Retrieved from http://www.frbsf.org/community-development/files/revisiting_cra.pdf.

[10] Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, Exploring Special Purpose National Bank Charters for Fintech Companies (December 2016) (citing bank regulatory policy at: 12 CFR 5.20(f)(1)(ii) and (iv)).

[11] 12 U.S.C. § 4501(7).

[12] 12 U.S.C. §§ 4562, 4563.

[13] Federal Housing Finance Agency, Enterprise Duty To Serve Underserved Markets, 12 CFR Part 1282 (December 29, 2016). Retrieved from https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2016-12-29/pdf/2016-30284.pdf.