Summary

The CFPB is on a roll -- and the public stands to benefit from the cascade of strong actions the agency is taking this spring.

It’s about to get harder for abusive financial services firms to take advantage of consumers.

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) issued guidance yesterday on what constitutes an abusive act or practice. This is a crucial step in ensuring a fair marketplace for consumers. When a company obscures important features of a product or service or takes advantage of a consumer’s lack of understanding, reliance or unequal bargaining power, there must be accountability. Although the CFPB has exercised its authority to stop abusive practices many times since Congress enacted the Dodd-Frank Act in 2010, this is the first time it has issued clear and concise guidance to aid consumers. This guidance, along with the existing federal guidance on deceptive and unfair acts or practices, helps ensure that anti-consumer conduct will be addressed and not slip through cracks.

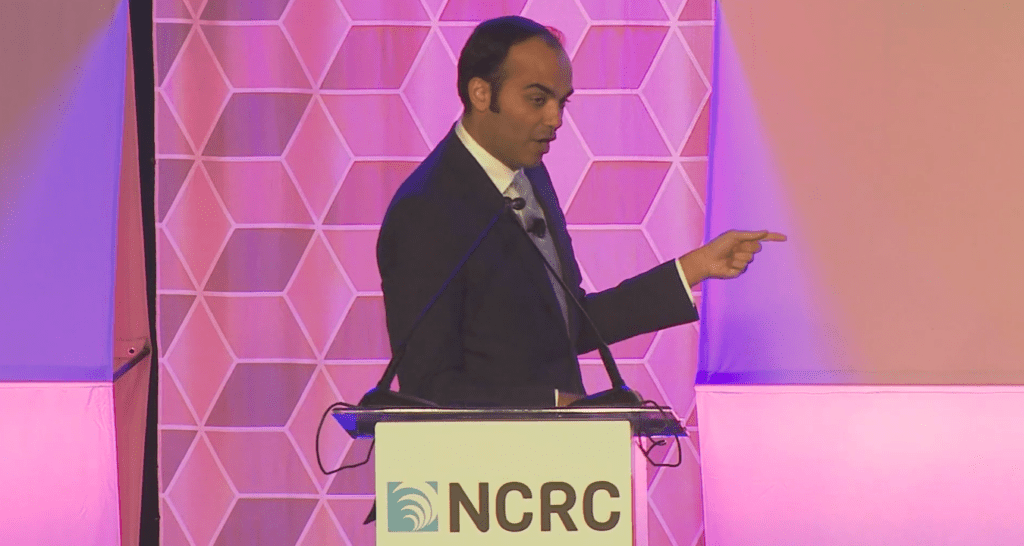

This is the second time in a week that the CFPB has taken care of some long-unfinished business related to the Dodd-Frank Act. CFPB Director Rohit Chopra last week announced final rules implementing the Small Business Data Collection Rule (known as Section 1071) to an appreciative crowd at NCRC’s Just Economy Conference. The rule – thirteen years in the making – ensures there will be more transparency as small business lenders will be required to publicly disclose demographic information about companies they accept and reject for credit, as well as information about the pricing and other terms of the loan.

As with Section 1071, the CFPB’s road to providing guidance on abusive acts or practices has also been long and winding. In January, 2020, the Trump-era CFPB issued a version of the guidance which would have been hard to enforce and easy to evade. That faulty policy would have only allowed a claim for abusiveness if the harm to the consumer outweighed “benefits” to consumers – which were not clearly defined. That version of the guidance also precluded an abusiveness claim if there was also a claim of deceptiveness or unfairness that could be brought against the same defendant for the same conduct – even though nothing in the Dodd-Frank Act limited multiple claims and decades of jurisprudence allowed claims of both deceptiveness and unfairness against the same defendant. Finally, the previous guidance did not allow for civil money penalties if there was evidence the defendant had attempted in good faith to comply with its interpretation of the law. This left an opening large enough for a truck to drive through: As long as a lender was willing to argue it made an honest mistake, its abusive conduct would go unpunished and no fines would be levied.

The Biden administration rescinded the Trump-era rule on March 11, 2020, to the relief of consumer advocates – and even many in the financial services industry who found the Trump-era guidance difficult to follow.

The new abusiveness guidance does not suffer the faults of its ill-fated predecessor. It provides examples of how a company can materially interfere with a consumer, take unreasonable advantage of a consumer and ways in which a consumer might be unable to protect her interest and be negatively impacted by reliance on a company. The CFPB makes it clear in the guidance how all of these elements of abuse are rooted in specific language of the Consumer Financial Protection Act. It also provides examples of abusive practices, including use of digital interference, complex jargon, a myriad of check boxes and omission of material terms among others.

The guidance is a strong statement by the CFPB of its intent to continue to bring claims of abusiveness where they are warranted and supported by evidence of anti-consumer behavior. The CFPB has already brought 43 cases that include a claim of abusiveness. So this is not the agency’s first rodeo. It is proceeding with some significant experience in the area that helped inform its guidance. The CFPB’s action yesterday is a welcome and necessary step to fulfill Congress’s intent that the agency combat abusive acts and practices – and that consumers understand when they have been the victims of financial abuse.

Brad Blower is NCRC’s General Counsel.