Good afternoon Chairman Meeks, Ranking Member Luetkemeyer and the Members of the House Subcommittee on Consumer Protection and Financial Institutions. Thank you for the opportunity to testify and for convening this important hearing on the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) to discuss the winners and the losers in the proposed rulemaking formally published last week by the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) changing the regulatory framework for the law. I am the Director of Policy and Government Affairs of the National Community Reinvestment Coalition (NCRC). NCRC and its more than 600 grassroots member organizations create opportunities for people to build wealth. NCRC members include community reinvestment organizations; community development corporations; local and state government agencies; faith-based institutions; community organizing and civil rights groups; minority and women-owned business associations, as well as local and social service providers from across the nation. We work with community leaders, policymakers and financial institutions to champion fairness and fight discrimination in banking, housing and business.

Comptroller Joseph Otting has really led this CRA regulatory reform process from the very beginning and the agency has lived up to its promise to put forth a “transformational approach” to the CRA regulations for the nation’s largest banks. The proposed changes are substantial, dilutive and would weaken the effectiveness of the law. I can say, without equivocation, the winners would be the nation’s largest banks and the losers would be low- and moderate-income (LMI) and underserved borrowers and communities, and importantly, the CRA ecosystem that has been built since to support economic opportunity in LMI communities in both urban and rural areas.

While we are certainly at odds with the Comptroller over this notice of proposed rulemaking (NPRM), NCRC has a long history of working with both OCC and FDIC and we recognize that a great deal of time and effort has gone into this reform framework. Nonetheless, we could not agree more with the very apt assessment of FDIC Board Member Martin J. Gruenberg that: “this is a deeply misconceived proposal.”

Introduction

In this testimony, I will summarize concerns on both this rulemaking process as well as the substance of this proposal, but we will provide more in the coming days. Given its complexity, we have focused on what we believe to be the largest and most significant issues. NCRC and our member organizations of CRA practitioners around the country are still adding to our analyses of this proposal – its new benchmarks, thresholds, definitions, standards, data collection, reporting and disclosure requirements – as well as how all the pieces would all fit together in a new regulatory schema. And, importantly, how they will impact bank performance standards and CRA ratings.

Today, about 98% of banks pass their CRA exams – a pass rate that suggests higher levels of lending, investment and financial services in low- and moderate-income (LMI) and underserved communities than actually exists.[1] Despite the paucity of underlying data and impact analyses in the proposed rule, CRA grade inflation is unmistakable in the central features of this proposal – a single metric as the dominant determinant of the CRA rating, an expanded list of eligible and qualifying CRA activities diluting the law’s effectiveness, and all triggering presumptive CRA ratings that allow banks to garner passing scores at the bank-level even as they have failing CRA scores in nearly half of their local communities/local assessment areas. Importantly, under the framework, banks would appear that they are doing more in the coming years in the dollar volume of CRA activities, but those activities would be less impactful, less targeted to LMI individuals and underserved communities, and with less effective strategies to respond to local credit needs.

CNN Business’ Before the Bell newsletter reported this weekend, that the largest U.S. banks made more than $120 billion in 2018, an all-time high. And, last year may have been even better. CRA standards for lending, investing and serving LMI and underserved communities should be strengthened and not weakened, plain and simple.

CRA: The Law’s Origins & Purposes

A. A response to actual redlining and on-going discrimination

The CRA was one of several landmark pieces of legislation enacted in the wake of the civil rights movement intended to address inequities in the credit markets. By passing the CRA, Congress aimed to reverse disinvestment associated with years of government policies and lending discrimination that deprived lower-income areas and communities of color of credit by redlining —using red-inked lines to separate neighborhoods deemed too risky.[2] The 1977 Congressional hearings leading to the enactment of the CRA documented conditions of redlining and unequal access to lending in the 1970s, but the phenomenon of redlining extended decades prior to the 1930s. The federal Home Owner’s Loan Corporation (HOLC) drew maps of city neighborhoods and differentiated them according to risk as perceived by industry professionals working for the federal government. The highest risk and “hazardous” neighborhoods were overwhelmingly minority and lower income. With federal government approval, these neighborhoods were then systematically redlined by lending institutions for decades. In a recent report, NCRC found that the neighborhoods classified as “hazardous” have remained predominantly minority and lower income.[3]

According to one study of redlining in 51 American cities, 86% of African Americans lived in a neighborhood marked for credit redlining in 1940, despite making up just 8%of the study’s population. [4] By contrast, only 35% of whites lived in redlined areas in 1940 despite making up over 90% of the sample population. Today, once-redlined neighborhoods continue to lag behind non-redlined areas on key economic indicators, such as homeownership rates and house values. Causal studies of the effects of HOLC redlining are few, but the literature is growing, finding: redlining maps increased racial segregation, while depressing homeownership, house values, and rents;[5] redlining maps had significant and persistent negative effects on new construction and population density.[6] Both of these studies do find, however, that the negative effects of redlining—particularly with respect to lower homeownership rates and higher levels of racial segregation—have become more muted since 1980. This is consistent with the effectiveness of the CRA as anti-redlining legislation and raises the broader question as to why and how the CRA has been effective.

B. A response to market failures

In economic terms, the CRA can also be seen as a response to what are known as “market failures”, including negative and informational externalities associated with a lack of lending and investment in LMI,[7] underserved communities and communities of color. For example, if lenders fear that other lenders will not lend to areas that are perceived to be risky whether they are or not, other lenders will withhold lending due to this fear, resulting in “self-fulfilling prophecy redlining.” The inability to borrow to buy and improve homes consigns neighborhoods to continuing disinvestment. The absence of home sales makes neighborhoods riskier because appraisers rely on sales to provide information on the value of homes in order to determine appropriate loan amounts. Information externalities and asymmetries can result in delays, caution about perceived risk, and banks charging higher interest rates. Lender expectations of this sort can cause a potentially viable market to suffocate from lack of credit. In the process, borrowers who may otherwise be credit-worthy will be denied credit because of the absence of entry by competitive lenders.

The CRA can be understood as a vehicle for facilitating coordination and for assuring banks that they will not be the lone participants in thinly-traded markets.[8] The Act and its regulations have produced positive information externalities that allow all lenders – both those covered by the CRA and those not covered by the CRA – to better assess and price for risk. By conferring an affirmative and continuing obligation on banks to help meet the credit needs in all of the neighborhoods they serve, the CRA has not only prompted banks to be more active lenders in LMI areas, but also important participants in multisector efforts to revitalize communities across the country.

C. CRA at the heart of a vibrant ecosystem

Due to the CRA’s statutory design and the existing regulatory framework, banks have made good strides in LMI markets and communities of color.[9] They have taken numerous steps, including establishing loan products geared towards LMI borrowers, entering loan pooling arrangements, undertaking lending consortiums, partnering with local groups, community development corporations and community development financial institutions (CDFIs) to break down the barriers that impede the efficient flow of capital into LMI communities. One accounting and tax advisory firm estimated that the banking sector was the source of 85% of the $10 billion in capital committed to housing tax credit investments in 2012.[10] When bank investors were surveyed about why they were so attracted to housing tax credit investments, they said the principal motivation were their obligations under the CRA investment test. The OCC and FDIC’s proposed general performance standards for the nation’s largest banks undermine these important benefits of the law –- the incentive for banks to develop partnerships with local community organizations and other stakeholders to address community needs – because the banks can satisfy their CRA obligations by simply hitting the metric. And, they could hit the metric with an expanded list of eligible and qualifying activities.

The OCC and FDIC’s Proposed Rule

On the Process

A. A patently unfair 60-day comment period

At the outset, we believe there have been critical missteps in the rulemaking process, including the 60-day length of the public comment period. The agencies must extend it. The OCC and FDIC should heed Chairwoman Maxine Waters and Ranking Member Sherrod Brown and the Members of this Committee and Senate Banking calling for and extension of the comment period. The 240-page proposal is dense, complex and has many interlocking pieces – in terms of how all the new benchmarks, thresholds and definitions fit together. Neither the 60-day timeframe nor the information provided in the notice of proposed rulemaking (NPRM) offer a meaningful opportunity to comment.

The NPRM is a fundamental rewrite of the CRA regulatory framework. An entire retail lending, community development and affordable housing infrastructure for low- and moderate-income individuals and communities is built around and reliant upon it working. On last Friday, the OCC released a request for information (RFI) related to deposit and other bank data limitations acknowledged by the agencies in the NPRM. That comment period closes one day after that of the NPR. As described above, the CRA ecosystem is vast. It has benefited LMI and minority home buyers, small farms, credit starved sole-proprietors, small- and minority-owned and women-owned businesses in low- and moderate-income communities and the incubators and cooperatives that provide technical and other assistance to them, housing tax credit investors and syndicators, non-profit and mission affordable single-family and multifamily housing developers, state and local housing finance agencies, community and economic development corporations, CDFIs and Indian country to name a few. The existing CRA regulatory structure which examines the nation’s largest banks under a retail lending test, investment test and service test.[11] The stakeholder community is vast, the proposal is multi-layered and connected with other public and private programs and incentives and multisector efforts. A 60-day comment period is simply unfair to the community of stakeholders that are tasked with understanding the various aspects of the proposal and how it would impact their work and their communities. The proposal cannot be understood, digested and analyzed in 60 days, plain and simple.

B. Missing data, analysis referenced in the proposed rule and impact on bank ratings of the various new empirical benchmarks and thresholds

Commenting on the proposal in the 60-day window is further hampered by the lack of data and impact analysis in the proposal. While the agencies have provided an illustrative list of bank activities that qualify and they have provided some cursory descriptions of their methods, they have provided very little of the underlying data or referenced analyses supporting their various empirical benchmarks and thresholds and virtually no impact analysis.

1. The Federal Reserve’s data and analysis

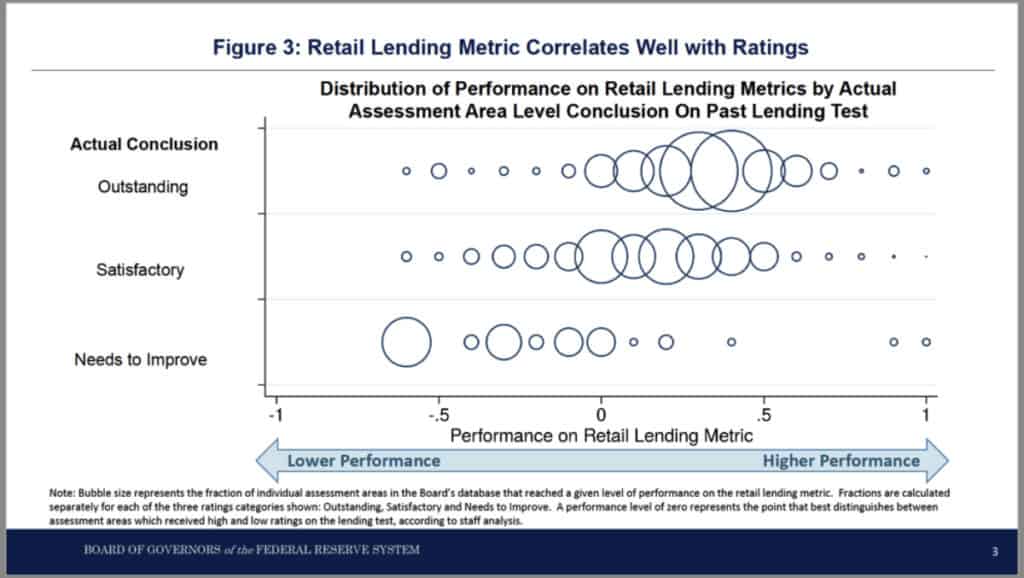

The contrast is best illustrated by some of the charts and graphs provided last week by Federal Reserve Governor Lael Brainard at the Urban Institute[12] in describing that agency’s approach of creating multiple metrics that would be more familiar to the organizations that are in the CRA space based on public data sources. The agency built a CRA database based on 6,000 written public CRA performance evaluations since 2005 from a sample of 3,700 banks of varying asset sizes, business models, geographic areas and bank regulators. It also spans economic cycles. Based on that database, Governor Brainard was able to illustrate how their proposed retail lending metrics, for example, correlate well with past ratings of bank performance.

The specific thresholds that would establish a presumption of satisfactory performance could be informed, Governor Brainard said, by current evaluation procedures but need not be set at the same level as today. Proposed metrics with the kinds of outcomes the law mandates combined with the data and underlying analyses would allow the public to understand what metrics would replicate past CRA ratings and examiner expectations. The public could then have an informed discussion and provide public comment about how those metrics could be adjusted to reflect the law, goals and priorities going forward. It is a better starting point for an informed discussion about how proposed metrics in terms of transparency, clarity and impact and a basis for meaningful public comment.

2. The OCC’s methods

The OCC relied on a sample of over 200 CRA performance evaluations completed since 2011 for banks above the small bank asset threshold of $1.284 billion in 2019. They analyzed Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA) data, Call Report data and credit bureau data, information about community development investments and made some assumptions to estimate what banks’ average CRA evaluation measures would have been from 2011 – 2017. Based on their analyses, they developed “empirical’ benchmarks and various threshold levels of bank activities that would correspond with an Outstanding CRA rating (11%), Satisfactory (6%) and Needs to Improve (3%); set a 2% community development minimum at the local assessment area and bank-level; included a .01 credit for bank branches located in LMI and other underserved areas; set new retail lending test demographic or peer comparators at 55% and 65%, respectively, that the bank either meet, exceed or fail; new deposit-based assessment area requirements for banks that collect more than 50% of their deposits outside their branch network, in markets where they collect 5%.

The ability to provide informed comment on the proposal is frustrated by a lack of the agencies’ referenced analyses around the empirical benchmarks and other thresholds or a distributional analysis of the impact on bank ratings. They all appear to be arbitrary. For example, based on the agencies’ review of historical data, does a 2% community development minimum correlate well with CRA ratings today? Based on historical data, what do the agencies know about the distribution of banks above, below and around a 2% minimum today? What do the agencies know or estimate about how much essential infrastructure, for example, banks are financing today that would qualify towards that minimum that does not today? Do the retail lending metrics correlate well with today’s CRA ratings? What do the agencies know or estimate about how many more bank assessment areas would be designated under the new deposit-based thresholds?[13]

Quite frankly, the agencies have failed to “show their work” and without having a better understanding or at least the agencies referenced analyses, the agencies estimates about how these benchmarks and thresholds compare with past ratings as well as distributions across the various scoring ranges, the public cannot provide informed input about the general performance standards, where these various markers should be set to reflect the laws, mandates and Congressional objectives as well as larger public policy and societal goals. The ability to meaningfully comment is truly frustrated.

C. The agencies must complete the data RFI first

On Friday, the OCC also released a RFI on the data that will supplement their historical data and assumptions related to retail domestic deposit activities, CRA qualifying activities and various retail loan data, including those originated and sold in 90 days. How the agency will supplement the existing historical data and assumptions is a critical piece that will inform bank capacity as measured by the base/the denominator of the OCC’s single metric – the CRA evaluation measure, the designation of new deposit-based assessment areas and well as other benchmarks, thresholds, information collection, reporting and disclosure requirements underlying these new small bank and general performance CRA standards. It would also inform how the regulators propose to verify a bank’s sample data used to determine compliance with the presumptive CRA ratings. It must be completed and a final rule published before the public comment period for the NPRM closes. Without knowing and understanding critical data and verification pieces around bank capacity and existing and new assessment areas, as just two examples, the ability to provide informed and meaningful comment would be frustrated for the hundreds of CRA practitioners we represent.

The Proposed Rule

On the substance

Attached is a powerpoint which reflects what the OCC and FDIC are proposing and some of our concerns. This is a brief summary of some of our concerns, as well:

CRA Evaluation Measure – an overly determinative single metric; rationing of CRA credit

The CRA evaluation measure that would apply to all of the nation’s largest banks and small banks that opt into the new general performance standards relies on a numerator inflated by an expanded list of CRA qualifying activities and a denominator of retail domestic deposits that is data limited and finite. Particularly in the case of community development activities, a rationing of CRA credit would occur as large and easy projects across the nation become the enemy of smaller, more complex but impactful local projects.

Presumptive CRA Ratings – arbitrary benchmarks; missing agency impact analysis; undermines the economic rationales for CRA

The proposed presumptive CRA ratings for Outstanding, Satisfactory and Needs to Improve appear to be arbitrary. The agencies have provided a cursory overview of data sources and assumptions they used to arrive at these empirical benchmarks, but they have failed to provide what they know about how banks would perform under them. Are more banks estimated to achieve Outstanding CRA ratings under these benchmarks than today, for example? The presumptive ratings, within this overall single metric framework, undermine what CRA has done very well: encourage the various kinds of community partnerships and loan pooling arrangements that help overcome the various market failures, negative and informational externalities that can be major roadblocks to attracting bank investment in low-income, distressed and underserved communities.

Expansion of CRA Qualifying Activities – extends CRA credit to bank activities done in the ordinary course of business; upends exam incentives that keep LMI considerations at the heart of the law.

The proposal broadens categories of CRA credit, including infrastructure and community facilities and volunteer activities by bank employees, for which banks are now proposed to get partial CRA credit all across the country. Banks would no longer have to have a “primary purpose” of community development targeted on LMI individuals and areas, small businesses or small farms, or underserved distressed rural areas. Even more of the smallest businesses and farms, for example, will be frustrated in their efforts to get bank credit and smaller dollar credit since key dollar loan size and gross annual revenue thresholds would be doubled and more for farms.

Facility-Based and New Deposit-Based Assessment Areas (AAs) – serious deposit data limitations; arbitrary deposit-based thresholds; no estimates of how many credit deserts would be served.

Though updates are certainly needed for internet and online banking, the regulators acknowledge the inadequacy of today’s deposit data to designate new areas or to develop a CRA evaluation measure based on local deposits. The regulators also assume that the thresholds they are proposing for when banks designate deposit-based AAs will encompass banking deserts, but they don’t explain why they assume it. The general CRA performance standards will also mean the nation’s largest banks will get a lot more credit for bank activities outside of AAs without any certainty they are qualitatively meeting local credit needs before then racking up a lot of partial credit around the nation for projects that really don’t need a CRA credit to get done.

Retail Lending Distribution Test – arbitrary demographic and peer thresholds; weaker incentive for banks to provide homeownership opportunities, small business and small farm loans to LMI borrowers and areas.

The agencies do not provide estimated pass rates for how banks would perform under their lending distribution benchmarks when compared to either the local demographics or the bank’s peers. It could set a low “pass” bar in those instances where the LMI population is high, but peer lending is low. The pass-fail retail lending test also does not consider the quality of the lending (e.g. high-cost consumer loans; how many small dollar mortgages are being made) and drops all place-based review of home mortgages in LMI neighborhoods. The retail lending test is weakened on the exam – it would have far less weight and banks could fail in half of their local AAs and still achieve a bank-level passing CRA grade. National policy efforts and the role of the nation’s banks in closing homeownership gaps and related racial and other wealth gaps get harder.

The Service Test – proposal virtually eliminates it; minimal recognition of bank branches in LMI areas; no consideration of affordable financial services and products.

The proposal has expanded CRA credit for general volunteer work of bank employees, including for financial literacy regardless of income, but eliminates consideration of bank’s efforts to provide affordable products, low-cost transaction and savings accounts and services intended to expand access to the banking system to low- and moderate-income individuals who are currently unbanked. Importantly, the percentage point credit for the number of bank branches in LMI and other underserved areas is not enough of an incentive and there would be no review of banks openings and closings.

Conclusion

Thank you for the opportunity to testify on the CRA. The OCC’s and FDIC’s proposal is deeply flawed. We urge the Members of this Committee to join us in opposing this framework and facilitating interagency coordination by all three of the prudential regulators around a common but far better approach that will clarify but strengthen the CRA’s regulatory framework for LMI people, underserved communities and communities of color.

Attachments:

1. NCRC powerpoint slides of the OCC/FDIC proposal and topline concerns

2. NCRC examples of absurd CRA qualifying activities in the NPRM

3. A Step-by-Step Summary of the OCC’s Proposed Ratings Mechanics (Covington)

4. The Banker’s Quick Reference Guide to CRA (today’s exam for large banks)

[1] For example, according to NCRC’s review of FFIEC data, in 2019, 7 percent of banks received a CRA rating of Outstanding; 91% received a rating of Satisfactory; 2 percent received a rating of Needs to Improve; 0 received a rating of Substantial Noncompliance. In 2018, 10% received a CRA rating of Outstanding; 89 percent received a rating of Satisfactory; 1 percent received a rating of Needs to Improve; 0 received a rating of Substantial Noncompliance. See also NCRC’s Grade Inflation Infographic: How Well are Regulators Evaluating Banks Under the Community Reinvestment Act?

[2] See Richard Rothstein, The Color of Law: The Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2017). See “Mapping Inequality: Redlining in New Deal America” (2016), for a compilation of the maps and notes created by the federal Home Owners’ Loan Corporation in the 1930s that designated areas considered too risky for mortgage lending and were used to determine eligibility for Federal Housing Administration guarantees.

[3] Bruce Mitchell, PhD. and Juan Franco, March 2018, HOLC “Redlining” Maps: The Persistent Structure of Segregation and Economic Inequality, NCRC, March 2018, https://ncrc.org/holc/

[4] Krimmel, Jacob and Wachter, Susan, The Future of the Community Reinvestment Act, PENN IUR Brief, (September 2019); Krimmel, Jacob. “Persistence of Prejudice: Estimating the Long Term Effects of Redlining.” Working Paper, University of Pennsylvania, 2018.

[5] Aaronson, D., Hartley, D. A., & Mazumder, B. The Effects of the 1930s HOLC “Redlining” Maps. Chicago Fed Working Paper (2017).

[6] Krimmel, at footnote 4.

[7] Robert E. Litan, Nicolas P. Retsinas, Eric S. Belsky, Susan White Haag, The Community Reinvestment Act After Financial Modernization: A Baseline Report, U.S. Treasury Dept., April 2000 (see p. 46, Economic Rationales); also, Ling, David C. and Susan M. Wachter. “Information Externalities in Home Mortgage Underwriting,” 44 Journal of Urban Economics (1998): 317-332 (provides evidence of information externalities in neighborhood decline). Guttentag, Jack M. and Susan M. Wachter. “Redlining and Public Policy.” Salomon Brothers Center for the Study of Financial Institutions Monograph Series in Finance and Economics, eds. Edwin Elton and Martin J. Gruber (New York University Graduate School of Business, 1980), 1-50.

[8] Ibid.

[9]A sample of research about the CRA and its effectiveness. Lei Ding and Leonard Nakamura, Don’t Know What You Got Till It’s Gone: The Effects of the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) on Mortgage Lending in the Philadelphia Market, Working Paper No. 17-15, June 19, 2017, https://www.philadelphiafed.org/-/media/research-and-data/publications/working-papers/2017/wp17-15.pdf; Lei Ding, Raphael Bostic, and Hyojung Lee, Effects of CRA on Small Business Lending, Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, WP 18-27, December 2018, https://www.philadelphiafed.org/-/media/research-and-data/publications/working-papers/2018/wp18-27.pdf; Governor Randall S. Kroszner, The CRA and Recent Mortgage Crisis, speech delivered at the Confronting Concentrated Poverty Forum, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, December 2008, https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/kroszner20081203a.htm; Is the CRA Still Relevant to Mortgage Lending? | Paul Calem, Lauren Lambie-Hanson, and Susan Wachter; Quantitative Performance Metrics for CRA: How Much “Reinvestment” is Enough? | Carolina Reid; The Community Reinvestment Act and Bank Branching Patterns | Lei Ding and Carolina Reid; NCRC, Access to Capital and Credit in Appalachia and the Impact of the Financial Crisis and Recession on Commercial Lending and Finance in the Region, prepared for the Appalachian Regional Commission, July 2013, https://ncrc.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/accesstocapitalandcreditInappalachia.pdf

[10] The Community Reinvestment Act and Its Effect on Housing Tax Credit Pricing, CohnReznick Report.

[11] See A Banker’s Quick Reference Guide to CRA (see also attached)

[12] Strengthening the Community Reinvestment Act by Staying True to Its Core Purpose, Governor Lael Brainard, January 8, 2020.

[13]For example, the OCC’s regulatory impact analyses says in relation to the small banks that “we believe that seven banks currently designated as wholesale or limited purpose banks may have increased data classification requirements.”

Check out Kim’s AC Contributor Page – click here. So putting

your site’s link on a page that consists of a lot of other links may

not do you that much good. Kim has 392 fans and keeps

them well entertained and equipped. http://sibayouth.s49.xrea.com/x/nbs/nbs.cgi