In 1926, historian and author Dr. Carter G. Woodson and the Association for the Study of African American Life and History (ASALH) established Negro History Week to celebrate the achievements of Black Americans and to foster a sense of collective memory for a people facing constant dehumanization. The ASALH has chosen the theme of “African Americans and Labor” for 2025, which “focuses on the various and profound ways that work and working of all kinds – free and unfree, skilled and unskilled, vocational and voluntary – intersect with the collective experiences of Black people.” From the cotton fields of the Black Belt to the northern factories of the Great Migration period to sitting behind the storied desk in the Oval Office, Black Americans have held practically every position of labor and power in the United States.

Today, the Black unemployment rate is near its lowest level on record, while Black wealth is at an all-time high. However, the Black unemployment rate has consistently remained 1.5 to 2 times higher than the White unemployment rate. In fact, 1.5 million more jobs are needed for the two rates to reach parity. It is not only the quantity of jobs that needs to increase in order to bridge this divide. The quality of jobs available must increase as well. Black workers, especially Black women, are more likely to work in lower-paying service jobs, such as entry-level retail roles or underpaying positions in the healthcare industry. Increasing the quality and quantity of jobs for Black Americans is irrelevant if they aren't able to be hired in the first place. With the freezing of the Civil Rights Division of the Department of Justice, ongoing labor market discriminatory trends of denying qualified Black applicants employment may worsen as bad actors become emboldened. Additionally, efforts to end diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) initiatives will hurt the labor market outcomes of Black workers.

On January 20th, President Trump put a freeze on most federal civilian hiring, limiting the ability of federal agencies to carry out their essential functions. Purges of public servants accompanied the freeze on federal hiring. News reports indicate the White House is placing special emphasis on removing employees deemed insufficiently loyal to the President, including high-level FBI officials, Justice Department personnel, and senior foreign aid staff. Included in the dismissals were so-called “DEI hires” (essentially Black officials), including Air Force General Charles ‘CQ’ Brown whose discussion of race and the military in a 2020 video during the height of the Black Lives Matter movement likely made him a target. Many of the firings lack a coherent explanation or rationale outside of the DEI and lack of loyalty frameworks.

Over a hundred FAA employees were fired, many of whom directly supported air traffic controllers or were involved in federal aviation regulation. The dismissals occurred weeks after the fatal Reagan National Airport crash that killed 67 people, a potential harbinger of what is in store. In another episode of questionable firings, 300 federal nuclear security workers were given pink slips, including some that oversee the country’s nuclear weapon facilities. After inquiries from members of Congress, their dismissals were reversed but the administration has run into difficulties reinstating them. Other suspicious firings include USDA workers during a bird flu epidemic, thousands of IRS employees during tax season, and the functional closure of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. While staff at the CFPB were told to halt their work and thus remain technically employed, the work stoppage of the agency threatens the financial security of all Americans and the economy as a whole.

These actions threaten a long-standing pathway towards stable, middle-class employment for Black Americans as 19% of the federal workforce is Black compared to 13% of the overall workforce. Part of the reason so many Black Americans work for the federal government is due to the unique history of federal employment’s progressive hiring and retention practices. Despite the rise of Jim Crow, federal workplaces in the 1890s were largely unsegregated, with Blacks and Whites working side by side. People of African American descent could be found working at all levels of the federal government. At the turn of the 20th century, President Theodore Roosevelt made some attempts to protect Black federal employees, especially at the United States Postal Service.

However, with the election of President Woodrow Wilson in 1912, the federal government began to mirror the increasingly segregated society around it, with middle-class and working-class Black Americans once again being relegated to menial roles. Despite this, labor shortages and Cold War exigencies led to the gradual reduction in race-driven labor market discrimination, including in the federal government. The US Postal Service experienced a rapid increase in Black workers, with the 1961-1966 period seeing the largest uptick in Black employment. This legacy remains today as 26% of postal workers are Black. Ongoing efforts to privatize the Postal Service not only threaten delivery access to rural communities but also threaten a pathway to the middle class for Black Americans.

The legacy of the public sector in helping build a Black middle class is most visible in the suburbs surrounding Washington, DC. Prince George's (PG) County has consistently been among the wealthiest Black communities in the country. Many Black federal workers who reside in PG County have shared concerns about the possible downsizing of the federal government. In the 1700s, PG County contained the largest population of Black slaves in Maryland. Following the Civil War, these newly freed people continued to work as sharecroppers and laborers on the same plantations they were formerly enslaved on. During the first half of the 20th century, the Black population rate declined with many going to Baltimore or Washington, DC, giving the latter its nickname: “Chocolate City.” Eventually, the desegregation of the federal government and the end of Jim Crow era apartheid made PG County a more viable place for Black Americans to live. PG County was 8% Black in 1960. By 1990, the Black population had tripled to over 490,000, or 62% of all PG County residents. Well-paying federal employment led to PG County becoming the wealthiest Black county in the country.

PG County isn't the only community to benefit from increases in federal employment opportunities for Black Americans. Established in 1967, Columbia, Maryland was designed to be a new type of city that would avoid the pollution, crime, and racism of other American cities. A shining example of the New Town Movement, Columbia became a go-to destination for the Black middle class with the Black population multiplying ten-fold from 1970 to 1980 alone. The establishment of Columbia, Maryland and its Black middle class was closely linked to the new employment opportunities offered through the federal government, with over half of the population employed by the federal government by the early 1970s. Columbia, Maryland is a classic case of the federal employment’s pivotal role in not only helping build a Black middle class but providing economic stability and growth to a municipality as well.

The federal government has played a unique role in the labor history of Black Americans. Attacks on the federal workforce are essentially attacks on Black wealth. As the current administration attempts to delete whole departments while firing temporary and probationary workers, little attention has been paid to the disproportionate impact these actions will have on Black Americans. Black-led organizations and allies have good reason to be especially engaged in the fight against job cuts and privatization schemes. The decades long progress made by Black federal employees is in serious danger of being upended in a fraction of time it took to build. Federal employment opportunities provide substantial economic independence and stability for Black middle class Americans and should be protected and expanded.

Joseph Dean is the Jr. Racial Economic Research Specialist with NCRC's Research team.

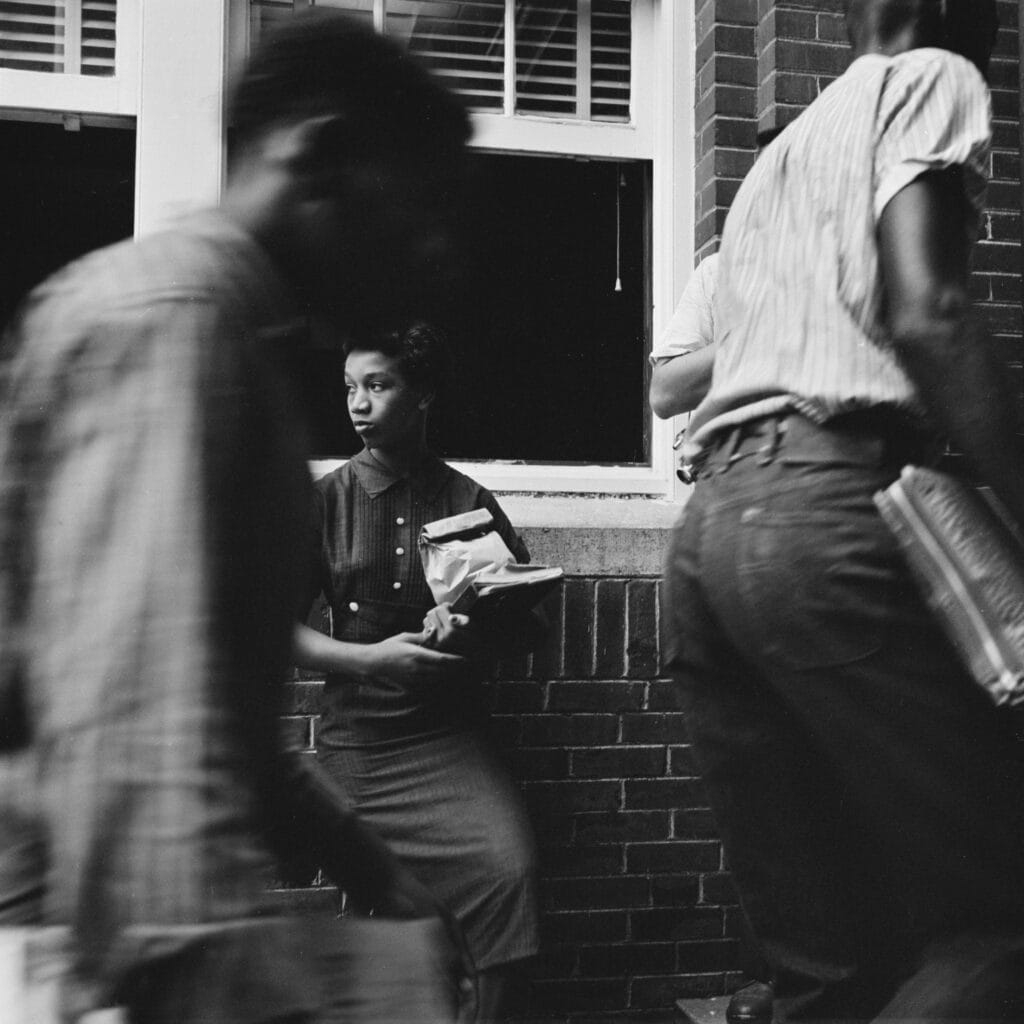

Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress.