What is Section 1071 Data?

The Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010 included Section 1071, which[1] mandated the collection and dissemination of data on applicants for loans to small businesses and women- and minority-owned firms. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) was designated to collect the data. The statutory purpose of the data is to aid in the enforcement of fair lending laws and to assess whether the needs of the businesses targeted by the law are being met.[2]

Why is Section 1071 Data Important?

- Small businesses drive economic growth and job creation in the United States. Small businesses are the prime source of employment for most of the workers in the United States and create approximately two out of every three jobs.[3] Therefore, policymakers and stakeholders need to know if these critical businesses are able to access safe and affordable credit or whether they face barriers in doing so.

- Women-owned businesses with employees account for about 20% of all employer businesses, number approximately 1.1 million and generate $1.8 trillion in revenue annually.[4] The CFPB estimates that an additional 10 million women-owned firms do not have employees.[5]

- Firms owned by people of color total about 8 million businesses and employ 7.1 million people.[6] While these figures seem impressive, the full economic potential of these firms is not realized if they experience disadvantages in the economy, including unequal access to credit.

- Disadvantages are often compounded by race and gender, suggesting a need for detailed loan data so experiences of women-owned businesses of color can be discerned.

- The Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City reported that 41% of African American female business owners were discouraged from applying for credit in contrast to 16% of White female business owners.[7] In addition, the average annual sales revenue for African American female business owners was $27,752 in contrast to $170,587 for White female business owners.[8]

Precedent Showing Impact of Improving Data Boosts Lending to Underserved Borrowers

After Congress updated HMDA data in 1989 to require information on the demographics of applicants, lending to minorities climbed in the 1990s before the advent of high-cost and abusive lending. For instance, from 1993 through 1995, conventional (non-government insured) home mortgage lending to African-Americans and Hispanics surged 70% and 48%, respectively. In contrast, the increase was just 12% for Whites.[9] A similar phenomena is likely to occur once the Section 1071 data on small business lending becomes publicly available.

Significant Disparities in Access to Loans by Race and Gender

- Disparities in loans received can impede the growth of businesses owned by people of color and women-owned businesses and thus impair overall economic growth.

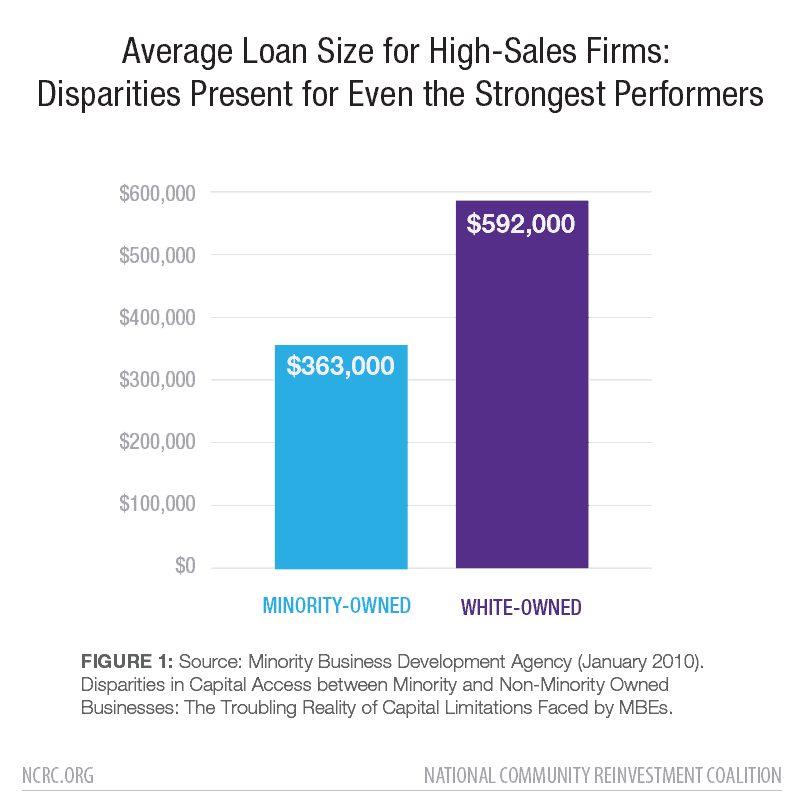

- The Minority Business Development Administration (MBDA) found that businesses owned by people of color received lower loan amounts than White-owned firms. This finding remained even after controlling for sales level of firms. The average loan received by high-sales firms owned by people of color was $363,000 compared to $592,000 for White-owned firms.[10]

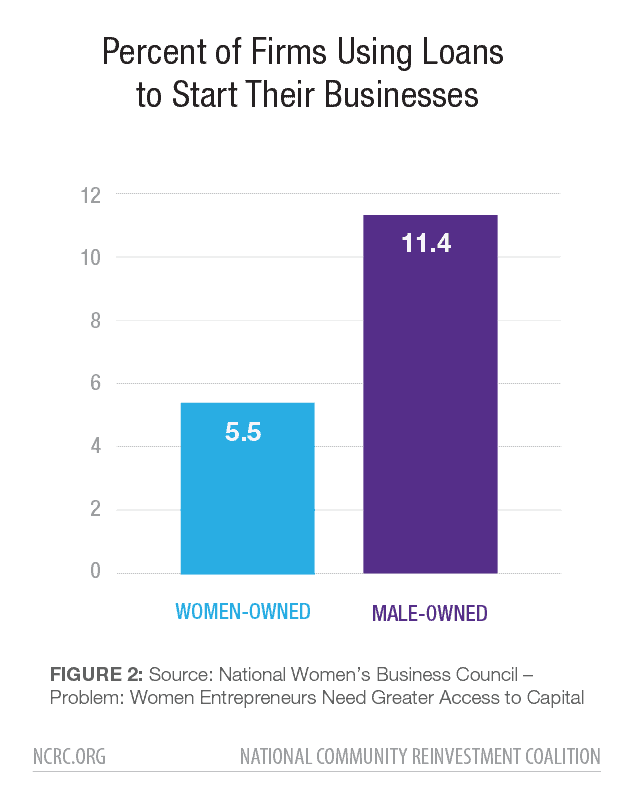

- Part of the difficulty women-owned businesses face is a lack of credit and capital. On average, women start their businesses with half as much capital as men ($75,000 compared to $135,000). Also, just 5.5% of female-owned businesses use bank loans to start their businesses, compared to 11.4% of male-owned businesses.[11]

- A Federal Reserve-sponsored paper reconfirmed previous findings that even after controlling for firm characteristics such as profitability and creditworthiness, firms owned by people of color are still more likely to be denied loans than White-owned firms.[12]

Small business ownership is an important wealth-building strategy in communities of color, but people of color face difficulties starting and growing their small businesses. Whites are twice as likely as people of color to own employer businesses (those with employees in addition to the owner).

- If people of color owned businesses at the same rate as non-minorities, our country would have one million additional employer businesses and more than 9.5 million additional jobs.[13]

- The smallest businesses also have more difficulties accessing credit; detailed Section 1071 data is critical to ascertain whether disparities by size of business remain or have widened. As revealed by survey data for the first quarter of 2012, just 18% of the small businesses with revenues less than $500,000 who sought loans obtained them. In contrast, 35% of the businesses with revenues between $500,000 and $1 million and 55% of the businesses with revenues between $1 million and $5 million received loans.[14]

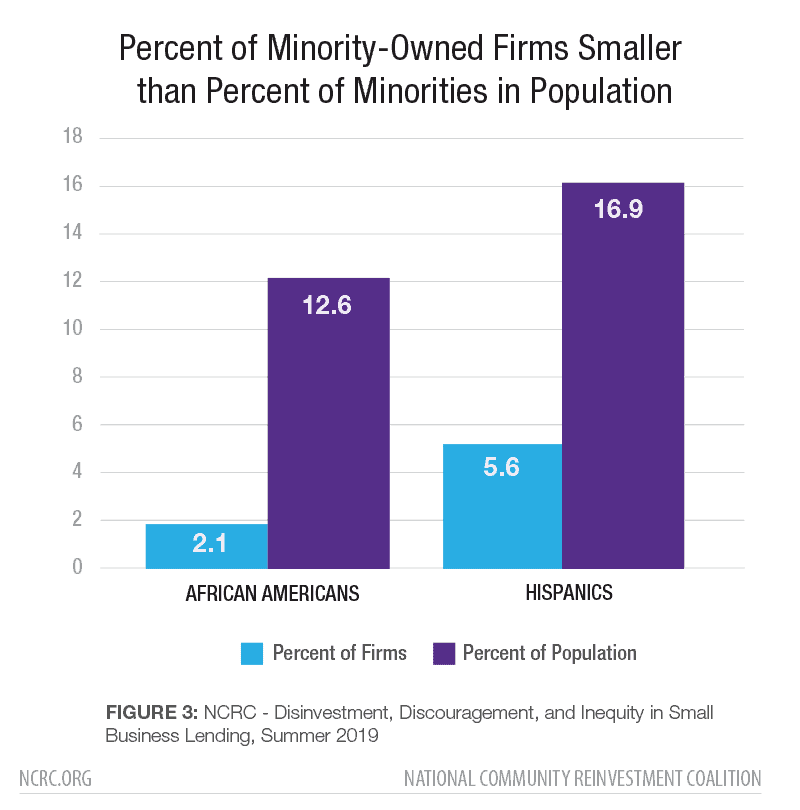

- According to NCRC, there are tremendous gaps in Black and Hispanic business ownership relative to their population size. Although 12.6% of the U.S. population is Black, only 2.1% of small businesses with employees are Black-owned. Hispanics are 16.9% of the population yet own only 5.6% of businesses.[15]

- In mystery shopping conducted by NCRC in Los Angeles, White testers were given significantly better information about business loan products, particularly information regarding loan fees, and White testers were told about what to expect 44% more frequently than Hispanic testers and 35% more frequently than Black testers.[16]

- NCRC surveyed more than 900 small businesses that had outstanding loan balances as of March 2020 with the intention of determining whether they had sufficient access to loan modifications during the pandemic. White small business owners who contacted commercial bank institutions received modification approvals at a significantly higher rate (26.7%) than Black (10.9%) and Latino (12%) small business owners who contacted these institutions.[17]

- The Federal Reserve reported that during 2020, only 13% of surveyed African American owned firms and 20% of Hispanic firms received the full amount of the loan funds they requested. In contrast, 40% of White-owned firms received the full amount of funding requested.[18]

The Section 1071 Database Must Comprehensively Cover Lenders

- In order for the Section 1071 database to accurately reflect the experience of small businesses and women- and minority-owned businesses, it must comprehensively cover depository and non-depository lending institutions. Any significant omission of a group of lenders will reduce the effectiveness of the data in achieving the fair lending purposes of the statute. The rule should exempt lenders only if they make fewer than 25 loans in a year as the CFPB proposed in its Sept. 2020 SBREFA outline and also consistent with the 2015 HMDA final rule that amended Regulation C.[19]

- Intermediate small banks (assets between $330 million and $1.322 billion)[20] were previously required to report small business CRA data. These banks were especially important in rural communities and smaller cities. Using CRA data from 2003, one of the last years in which intermediate small banks reported data, NCRC estimated that these banks were between 15% to 20% of the market in the Appalachian portion of states like Maryland and Virginia.[21]

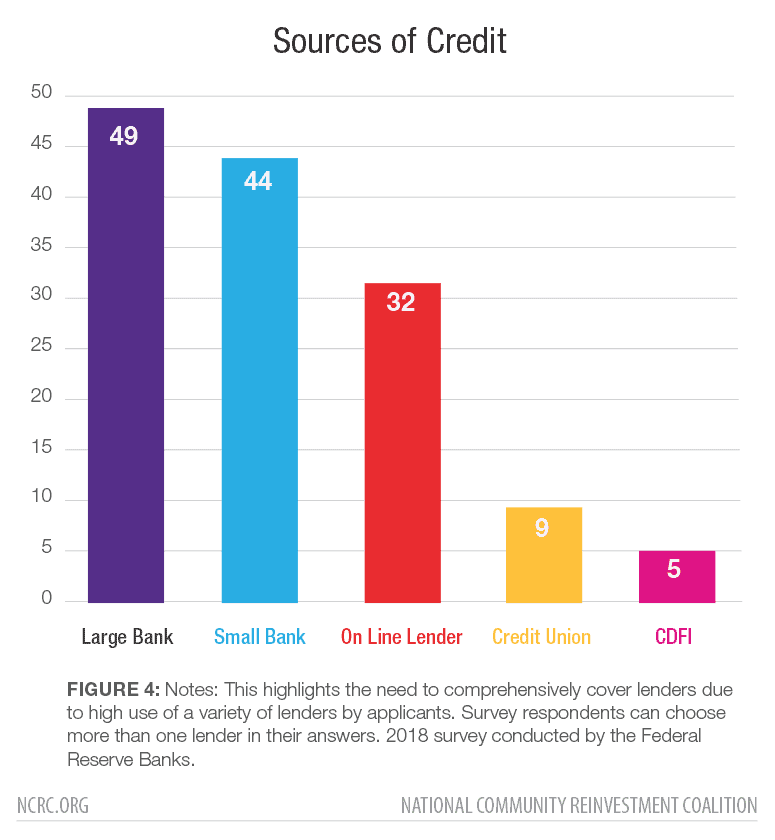

- More recent surveys reinforce the importance of resuming data disclosure requirements for small banks. A Federal Reserve survey found that 44% of small businesses applying for credit in 2018 applied to small banks.[22]

- Likewise, online lenders are a significant force in the marketplace today and will likely increase their market share with each passing year. By 2020, Morgan Stanley forecasted online lenders or fintechs reaching $47 billion, or 16% of total U.S. small and medium enterprise approvals.[23]

- A recent Federal Reserve survey reported that the share of survey respondents applying for business loans from online lenders increased to 32% in 2018, up from 19% in 2016.[24] The percentage decreased to 20% during 2020. Even during a pandemic, however, online lenders had considerable market share. Thirty-five percent of businesses with credit scores indicating medium to high risk applied to an online lender in 2020.[25]

- While credit unions have legal limits capping their small business lending, a number of credit unions have a significant presence in the small business lending marketplace. The Federal Reserve Banks found that 20% of business survey respondents with medium/high credit risk and with less than five years of operation sought financing from credit unions.[26]

Why Factoring and Merchant Cash Advances Must be in the data

Factoring and Merchant Cash Advance (MCA) agreements are widely used by small businesses, particularly very small businesses, who are more likely to face heightened challenges accessing conventional business credit. These forms of credit are expensive, not well understood by borrowers and subject to abuses. We urge the CFPB to modify the definition of credit for the purpose of Section 1071 to include merchant cash advance and factoring products.

- From 2013 to 2016, non-bank providers supplied an average of $94 billion in receivables-based financing to small businesses.[27]

- MCAs provide a business with an up-front lump sum payment (the advance) in return for a percentage of that business’s credit and debit card sales and should be reportable under Section 1071. Factoring operates in a similar manner.

- The MCA industry was estimated to have provided $19.2 billion in small business funding by the end of 2019.[28] One well-known MCA lender reported that it has issued 1 million MCAs, for a total amount of $6.3 billion, since 2014.[29]

- A CFPB white paper estimated that the number of factoring and merchant cash advances is about 8 million (7 million for factoring and one million for MCAs), which exceeds the 6 million loan term accounts.[30]

- The high cost of using an MCA can force small businesses into recurring debt traps. For example, a healthcare services non-profit that helped underserved communities, originally received $250,000 through an MCA but ended up owing $4.3 million in cumulative MCA debt.[31]

Pricing Information Must be in the Data

In addition to measuring access to loans, Section 1071 data must have information on pricing so that it can achieve its statutory fair lending objectives.

- It is vital to capture pricing of fintechs in the data since the highest percent of applicants (33%), according to a Federal Reserve survey, were unsatisfied with the high interest rates of their loans for online lenders compared to large and small banks.[32] In 2020, online lenders still had the lowest overall rates of satisfaction at 43%.[33]

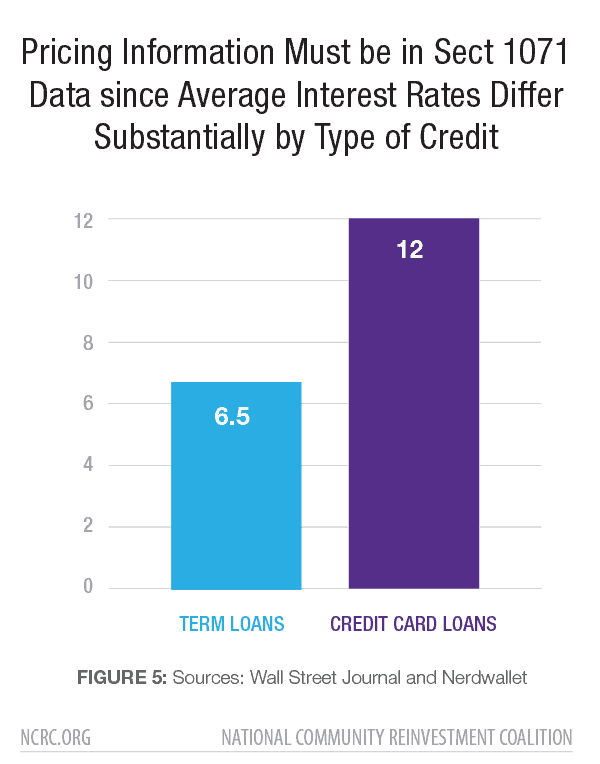

- Pricing for credit card and non-credit card lending must be in the Section 1071 database. Credit card loans are generally issued at higher interest rates than term loans and are used disproportionately by businesses owned by people of color.[34] Credit card rates average around 12.85% in comparison to 5% or 6% that is traditional for small business loans. Small businesses credit card spending rose by $215 billion between 2006 and 2015.[35]

- For text of the Dodd Frank Act and for Section 1071, see https://www.congress.gov/111/plaws/publ203/PLAW-111publ203.pdf. Text for Section 1071 can be found on page 682 of the PDF version. ?

- Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), Small business lending data collection rulemaking, https://www.consumerfinance.gov/1071-rule/ ?

- Mills, Karen Gordon and McCarthy, Brayden, Harvard Business School, The State of Small Business Lending: Credit Access During the Recovery and How Technology May Change The Game, p. 4, July 2014. ?

- Andrew Hait, Number of Women-Owned Employer Firms Increased 0.6% From 2017 to 2018, United States Census Bureau, March 2021, https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2021/03/women-business-ownership-in-america-on-rise.html ?

- Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), Key Dimensions of the Small Business Lending Landscape, 13, May 2017, https://www.consumerfinance.gov/data-research/research-reports/key-dimensions-small-business-lending-landscape/ ?

- CFPB, Key Dimensions, 15. ?

- Dell Gines, Black Women Business Startups, Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, https://www.kansascityfed.org/community/economic-and-small-business-development/black-women-business-startups/, p. 12. ?

- Gines, p. 9. ?

- NCRC, Home Loans to Minorities and Low- and Moderate-Income Borrowers Increase in the 1990s, but then Fall in 2001: A Review of National Data Trends from 1993 to 2001. Available upon request. ?

- Minority Business Development Agency (January 2010). Disparities in Capital Access between Minority and Non-Minority Owned Businesses: The Troubling Reality of Capital Limitations Faced by MBEs. p. 5, https://www.mbda.gov/sites/default/files/migrated/files-attachments/DisparitiesinCapitalAccessReport.pdf ?

- National Women’s Business Council – Problem: Women Entrepreneurs Need Greater Access to Capital, https://cdn.www.nwbc.gov/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/11091753/fact-sheet-access-to-capital.pdf ?

- Mels de Zeeuw, Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta Community and Economic Development Department, and Brett Barkley, Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland Supervision and Regulation Department (November 2019). Mind the Gap: Minority-Owned Small Businesses’ Financing Experiences in 2018. Consumer and Community Context, a Federal Reserve System publication, Vol. 1, No. 2, p. 16. https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/2019-november-consumer-community-context.htm ?

- Kauffman Foundation, State of Entrepreneurship 2017: Zero Barriers – Three Mega Trends Shaping the Future of Entrepreneurship, http://www.kauffman.org/~/media/kauffman_org/resources/2017/state_of_entrepreneurship_address_report_2017.pdf ?

- Josh Silver, Archana Pradhan (NCRC), Spencer Cowan (Woodstock Institute) (July 2013). Access to Capital and Credit in Appalachia and the Impact of the Financial Crisis and Recession on Commercial Lending and Finance in the Region. Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC), p. 86. https://ncrc.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/accesstocapitalandcreditInappalachia.pdf ?

- NCRC, Disinvestment, Discouragement, and Inequity in Small Business Lending, Summer 2019, https://ncrc.org/disinvestment/ ?

- NCRC, Disinvestment, Discouragement, and Inequity in Small Business Lending, Summer 2019, https://ncrc.org/disinvestment/ ?

- Anneliese Lederer and Sara Oros, Are Loan Modifications For Small Businesses A Possibility In The COVID-19 Pandemic?, February 2021, NCRC, https://ncrc.org/are-loan-modifications-for-small-businesses-a-possibility-in-the-covid-19-pandemic/ ?

- Federal Reserve System, Small Business Credit Survey: 2021 Report on Employer Firms, https://www.fedsmallbusiness.org/survey/2021/report-on-employer-firms, p. 23. ?

- 12 CFR Part 1003 (as amended October 15, 2015) and Consumer Financial Protection Bureau Releases Outline of Proposals Under Consideration to Implement Small Business Lending Data Collection Requirements, September 2020, https://www.consumerfinance.gov/about-us/newsroom/cfpb-releases-outline-proposals-implement-small-business-lending-data-collection-requirements/ ?

- Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System and Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, Agencies release annual CRA asset-size threshold adjustments for small and intermediate small institutions, December 17, 2020, https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/pressreleases/bcreg20201217a.htm ?

- Access to Capital and Credit for Small Businesses in Appalachia. (2007). National Community Reinvestment Association. https://ncrc.org/wp-content/uploads/2007/05/ncrc%20study%20for%20arc.pdf ?

- Federal Reserve Banks, Small Business Credit Survey, April 2019, p.16, https://www.fedsmallbusiness.org/medialibrary/fedsmallbusiness/files/2019/sbcs-employer-firms-report.pdf ?

- Karen Gordon Mills and Brayden McCarthy, The State of Small Business Lending: Innovations and Technology and the Implications for Regulation, Harvard Business School, 48, 2016. https://www.hbs.edu/ris/Publication%20Files/17-042_30393d52-3c61-41cb-a78a-ebbe3e040e55.pdf ?

- Federal Reserve Banks, Small Business Survey, 2019, executive summary, https://www.fedsmallbusiness.org/medialibrary/fedsmallbusiness/files/2019/sbcs-employer-firms-report.pdf ?

- Federal Reserve System, Small Business Credit Survey: 2021 Report on Employer Firms, https://www.fedsmallbusiness.org/survey/2021/report-on-employer-firms, p. 25. ?

- Federal Reserve Banks, Small Business Credit Survey: Report on Startup Firms, August 2017, 15. ?

- Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. (September 2017). Report to the Congress on the Availability of Credit to Small Businesses. Retrieved at https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/files/sbfreport2017.pdf ?

- Sweeney, P. (2019, August 19). ”Gold Rush: Merchant Cash Advances Are Still Hot.” Debanked. https://debanked.com/2019/08/gold-rush-merchant-cash-advances-are-still-hot/ ?

- Square. 2019 10-K, (2020, February 26). Annual Report filed to the Securities and Exchange Commission. Retrieved at https://s21.q4cdn.com/114365585/files/doc_financials/2019/q4/Square-2019-10-K.pdf In its filing, Square provides additional commentary on its lending model: “Generally, for loans to Square sellers, loan repayment occurs automatically through a fixed percentage of every card transaction a seller takes. Loans are sized to be less than 20% of a seller’s expected annual GPV and, by simply running their business, sellers repay their loan in eight to nine months on average. https://s21.q4cdn.com/114365585/files/doc_financials/2019/q4/Square-2019-10-K.pdf ?

- CFPB, Key Dimensions of the Small Business Lending Landscape, 21-22, May 2017, https://www.consumerfinance.gov/data-research/research-reports/key-dimensions-small-business-lending-landscape/ ?

- McLean, B. (2018, December 8). ‘We’re coming after you’: Inside the merchant cash advance industry. Yahoo! Finance. https://finance.yahoo.com/news/merchant-cash-advances-salvation-small-businesses-payday-lending-reincarnate-161835117.html?guccounter=1 ?

- Federal Reserve Banks, Small Business Credit Survey, 2017, p. 17, https://www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/media/smallbusiness/2016/SBCS-Report-EmployerFirms-2016.pdf ?

- Federal Reserve System, Small Business Credit Survey: 2021 Report on Employer Firms, p. 28. ?

- Small Business Administration, Office of Advocacy, September 2011, Frequently Asked Questions about Small Business Finance, https://www.sba.gov/sites/default/files/Finance%20FAQ%208-25-11%20FINAL%20for%20web.pdf, p. 4. ?

- Ruth Simon, Big Banks Cut Back on Loans to Small Business, The Wall Street Journal; citing PayNet studies on Small Business Lending, available at https://www.wsj.com/articles/big-banks-cut-back-on-small-business-1448586637. Also, see Steve Nicastro, Small-Business Loan vs. Business Credit Card: How to Choose, Nerdwallet, October 2017, https://www.nerdwallet.com/article/small-business/business-credit-card-small-business-loan ?

Featured image: ©Leonid – stock.adobe.com