Powerful corporations are mounting an audacious new attack on the federal government’s work to protect Americans from discrimination. They have neither logic, nor law, nor popular opinion on their side.

A coalition of corporate lobbyists recently sued in federal court asserting that the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) lacks authority to protect consumers from discriminatory practices. The lawsuit asserts that the CFPB cannot apply its authority to address unfair, deceptive, or abusive acts and practices (UDAAP) in combating discriminatory practices.

According to the plaintiffs, the CFPB’s recent decision to clarify its UDAAP enforcement practices was “arbitrary and capricious,” exceeded the regulatory authority given to it in the Dodd-Frank Consumer Financial Protection Act and was implemented outside of the rules set forth for regulatory action in the Administrative Procedure Act.

In essence, the lobbyists are arguing that using Dodd-Frank to empower a consumer protection agency to call out discrimination as unfair is a step too far, and a court should hamstring the CFPB’s independence and ability to shine a light on discriminatory conduct by eliminating the CFPB’s funding. The lobbyists assert this even though federal regulators have used unfairness as a way of combating predatory and anti-consumer business behavior for more than five decades with the approval of the Supreme Court.

What specifically was it that has so greatly raised the ire of these trade associations? Only that the CFPB has clarified that it can examine financial institutions for discriminatory practices in areas outside of lending.

The lawsuit responds to a March announcement by the CFPB that it would update its examination manual to evaluate activities other than lending to determine if they met the standard for a discriminatory practice and were thus unfair under its UDAAP authority. In the manual update, the CFPB stated that a harmful practice that leads to “foregone monetary benefits” or “denial of access to products or services” meets the test for causing “substantial injury.” The update did not expand UDAAP authority; it only clarified how the kinds of injuries prohibited as unfair under the federal consumer protection statute included more than just adverse credit decisions.

The CFPB has the legal standing, the expertise, and the instincts to review financial institutions for discriminatory activity. The CFPB has always had the right to supervise, write rules, and pursue enforcement against discriminatory practices. Congress allowed the CFPB to supervise institutions for discriminatory activities in lending under the Equal Credit Opportunity Act (ECOA). Congress also gave the CFPB, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and the banking regulators the ability to challenge unfair acts and practices. Congress did not define which specific acts and practices were unfair but defined the characteristics of an unfair act and practice which would clearly include discrimination.

The Chamber’s lawsuit is out of sync with the beliefs of the US Congress and the people of the United States.

What could be more unfair than discrimination? It seems obvious, and yet the US Chamber of Commerce, American Bankers Association, Consumer Bankers Association and other financial industry players want the federal courts to protect banks’ imagined right to discriminate from the oversight that Congress obviously intended CFPB to conduct. Their lawsuit amounts to an attack on the very idea that the federal government should protect consumers.

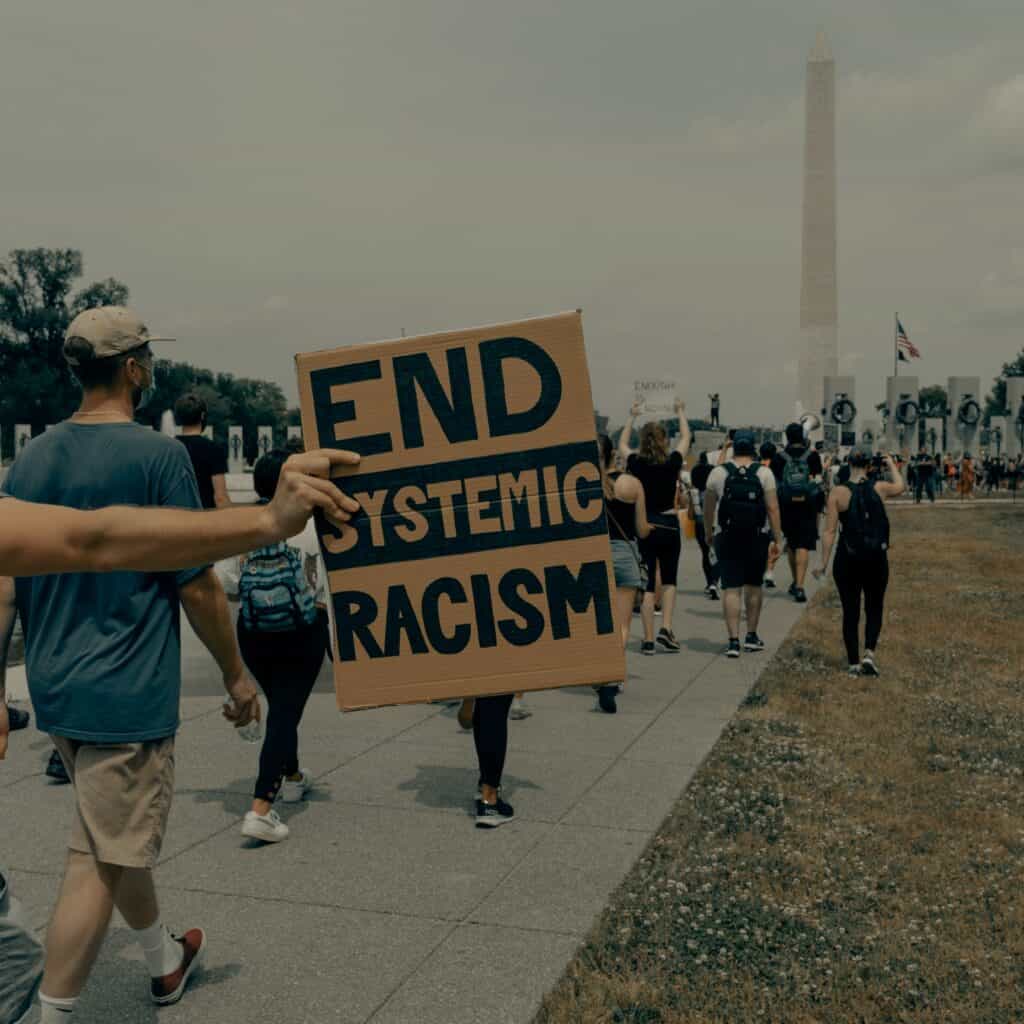

The suit ignores the expressed will of Congress, which gave the CFPB authority to protect consumers from discrimination in financial services, and expressly called for a funding structure immune to political pressure. It also ignores the contemporary crisis in America over systemic racism. Polls show that most Americans acknowledge the presence of racism in our country and believe it is a problem, and most Americans supported the protests after George Floyd’s murder.

It even moves past some of the prior statements from their members. After Floyd’s murder, banks expressed their commitment to racial equity. Some even said that they would seek to increase access to bank accounts for Black consumers. Some financial institutions have even filed comments to the CFPB asking it to do more to prevent discrimination. The bank trades’ new lawsuit puts a spotlight on corporate hypocrisy.

But by the carefully selected audience the plaintiffs have chosen for their lawsuits, they have done their best to ensure that their concerns will be heard before a judge who likely shares their views, no matter how different that arena might be compared to the rest of the country. The plaintiffs chose to take their case to the Eastern District Court of Texas, where a swath of conservative-leaning judges received appointments during the Trump Administration, and where an appeal would go to an appellate court that is also considered one of the most conservative in the country.

Efforts to give Congress power over the CFPB’s budget would circumvent the substance of how consumers are protected from discrimination under cover of a technocratic lens rooted in administrative decision-making.

Congress made the CFPB independent of the appropriations process because it knew powerful financial interests would oppose its work. Congress understood the financial crisis could only have occurred if regulatory agencies had become captured by private interests. At the time of the financial crisis, the Secretary of the Treasury was formerly the CEO of Goldman Sachs, the Comptroller of the Currency had previously lobbied for more than a decade for the American Bankers Association, and the Director of the Office of Thrift Supervision was a career community banker. With this eye to history, Congress designated the CFPB as independent actor, gave it funding that was not subject to appropriations, eliminated at-will firing privileges, and exempted it from review by the Office of Management and Budget.

Republicans have repeatedly sought to pare back the independence of the CFPB through failed efforts to amend Dodd-Frank to change the CFPB’s funding. During the Trump era, the administration eviscerated the CFPB’s Office of Fair Lending and Equal Opportunity, ultimately stripping it of enforcement powers. Trump’s choice to lead the CFPB, Mick Mulvaney, even turned away funding due to the Bureau that could have been used to enforce federal fair lending laws.

The new lawsuit revives this well-worn contention about the CFPB’s financial independence. Count IV of the complaint states that “the CFPB relies on this unconstitutional funding scheme to carry out its overly expansive UDAAP authority“ and “the CFPB’s funding scheme is distinct from other financial regulators.”

A key distinction between the funding structure of the CFPB versus that of the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) is that the CFPB is not funded by the financial institutions it regulates. Most of the revenues to support the OCC come from the assessments paid to it by its member national banks. A part of the Federal Reserve’s funding comes from assessments; none of its funding is derived from appropriations.

We all should be very concerned about both the intended and unintended consequences of this lawsuit. If it is successful it would be a precedent for questioning the funding streams supporting other government agencies. Many agencies receive support from sources outside the appropriations process. The corporate lobbyists who filed this case are opening a Pandora’s box. Their arguments have implications far beyond the context of the CFPB’s authority – implications that would hurt the businesses and banks these lobbying groups exist to serve. We suggest these lobbyists take a second look and reconsider.

Adam Rust is NCRC’s Senior Policy Advisor.

Brad Blower is NCRC’s General Counsel.

Photo by Clay Banks on Unsplash

Thank you for information about this lawsuit. It calls to mind financial institutions’ historic attempts to discriminate, such as redlining. This is despite their recent lackluster attempts to appear to be committed to do otherwise (e.g. – elimination/reduction of overdraft charges).

I am curious: are there any financial institutions who at least appear to not support/this lawsuit?